Indiana Organic Network: Cultivating community for Hoosier farmers

Communities rely on farmers to produce the food that sits on their dinner table, and farmers rely on consumers to provide a market for their harvest. When farmers need to know which providers to go to for the best seed, fertilizers and tractors, they most often turn to one another and to scientists for advice.

The community that forms across research, production and supply chains is a key piece of what makes agriculture a backbone of the American economy and culture. Some Hoosier farmers have also been experimenting outside of standard agricultural practices.

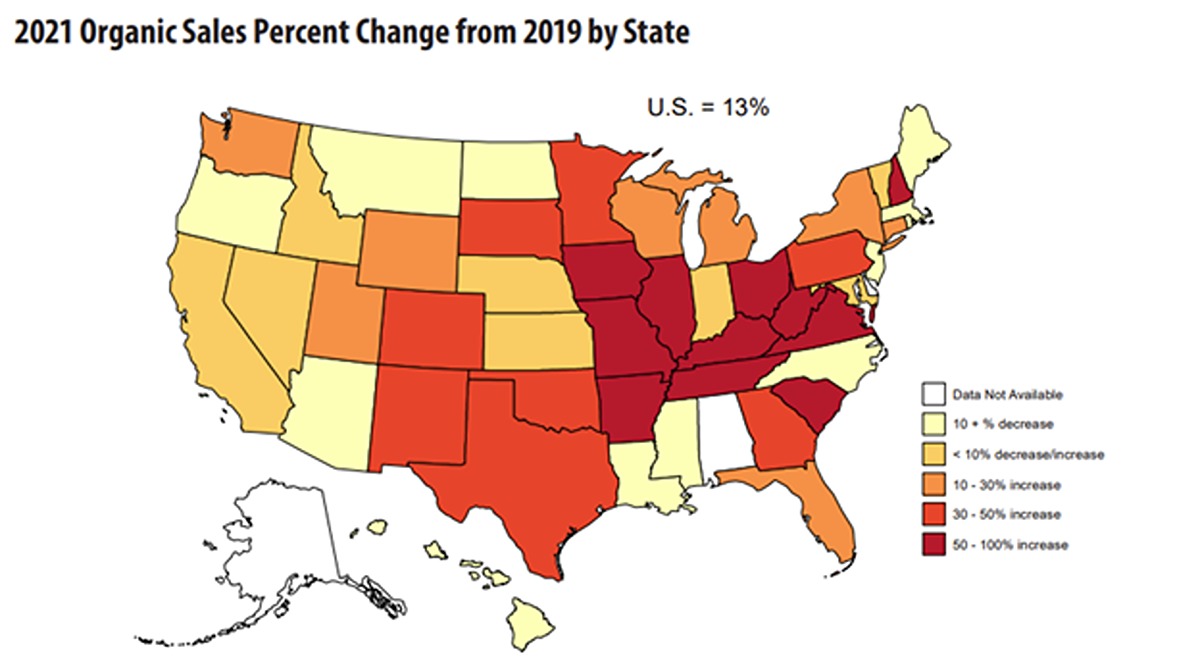

“If you look at USDA reports, all around us in the corn belt, states are making decent sales from organic agriculture except for Indiana,” Roland Wilhelm, assistant professor of soil microbiology in Purdue’s Department of Agronomy, said.

Organic agriculture differs from conventional agriculture through its inclusion of specific practices to benefit the environment and long-term health of the farm. While these farms are often smaller and require more intensive care than conventional fields, organic-grown produce can fetch a higher price at market.

However, the transition into organic production can be stressful for farmers who have questions that require individualized answers. Often, they call Extension professionals like Ashley Adair, an organic agriculture specialist in Purdue’s Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture.

However, the transition into organic production can be stressful for farmers who have questions that require individualized answers. Often, they call Extension professionals like Ashley Adair, an organic agriculture specialist in Purdue’s Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture.

“Many of my calls day-to-day are from people interested in transitioning their land. We talk about their goals for their farm, the knowledge they seek to farm and sell organic and what it's like to work with an organic certifier,” Adair said. “In my Extension programming, I also present information about the National Organic Program, important figures in the modern organic movement and how all that informs why our standards look the way they do here in the U.S.”

For farmers adding organic to their portfolio, they must figure out how to get the USDA Organic Certification and label for their product—which requires abiding by several more legal standards than conventional farmers.

“Organic agriculture can contribute to society through better soil health, environmental sustainability and good food,” Yichao Rui, an assistant professor of agroecology in agronomy noted. “But organic farmers need support to get a market to sell their crops. For organic farmers to market their additional crops in their rotation, there has to be market channels and vehicles to help them to get there.”

good food,” Yichao Rui, an assistant professor of agroecology in agronomy noted. “But organic farmers need support to get a market to sell their crops. For organic farmers to market their additional crops in their rotation, there has to be market channels and vehicles to help them to get there.”

Rui, Adair and Wilhelm saw how these gaps made organic farming less accessible and formed the Indiana Organic Network (ION) with other Purdue professors and local growers. Funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture, they connect organic farmers with each other to share expertise and ideas, as well as promote their work in a coordinated fashion.

Katy Rogers, the director of Teter Retreat and Organic Farm, said, “It’s critical that Indiana facilitates a plurality of agricultural models and practices. Farms can’t thrive without data and a support network, so we are grateful for ION and their assistance.”

Not only are the ION Purdue scientists trying to help build data to better report on the benefits and profitability of organic agriculture, but their relationship to the farmers also offers new opportunities for research. Organic farmers, already having to test their hand at new practices, are often open to working with scientists on farm trials.

Wilhelm said that the ION scientists are also inspired by what techniques organic farmers are experimenting with themselves. “From a research perspective, it’s kind of interesting. If you see something new and it works, then you have a research topic, right? With organic, you're inviting additional management complexity, and that complexity can be informative for researchers.”

ION is looking for more growers, market partners and interdisciplinary scientists to help them identify and solve challenges faced by organic farmers in Indiana. Adair hosts Extension events to update the community on recent research and any changes to standards and guidelines, and she helps ION farmers host on-farm visits to learn from each other. Wilhelm and Rui hope to engage with groups at these events to begin answering fundamental questions for Hoosiers, like where the organic products grown here can eventually be sold.

This research aims to benefit all farmers. What they learn by conducting surveys and testing new practices could eventually inform field management and create more options for organic and conventional production alike.