Research uses radar to expose sky’s organized, living habitat

Radar analysis reveals structured nature of lower atmosphere

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. — When people think about habitats on Earth, they likely picture forests, oceans or grasslands. Few think to look up. Yet the lower atmosphere, or troposphere, may be the largest habitat on the planet. A new study published in Ecology argues that this vast aerial expanse is an environment teeming with life.

Trillions of organisms, from birds to bats to insects, occupy this space — living, migrating, foraging, eating and even sleeping while in flight. By volume, the lower atmosphere is five times larger than the oceans.

“The lower atmosphere is an enormous ecological stage, but, for decades, it has remained largely invisible to us,” said Kyle Horton, associate professor of forestry and natural resources at Purdue University and a co-author of the article.

The Purdue AeroEco Lab is working to change that perspective. Their goal: to characterize where, when and how animals use the sky as habitat.

A continentwide view of life in the skies

Horton’s team tapped into the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s weather surveillance radar network called Next Generation Weather Radar, or NEXRAD, one of the most powerful tools used to study the atmosphere. Across the United States, more than 140 NEXRAD radars scan the horizons, collecting information about flying birds, bats and insects as well as measures of rain and snow.

Horton and his colleagues analyzed more than 100 million radar observations taken by NEXRAD sites between 1995 and 2022. From this data, they mapped daily cycles of aerial activity, identified the vertical “layers” where most migration occurs and measured the proportion of movement happening during the day versus at night.

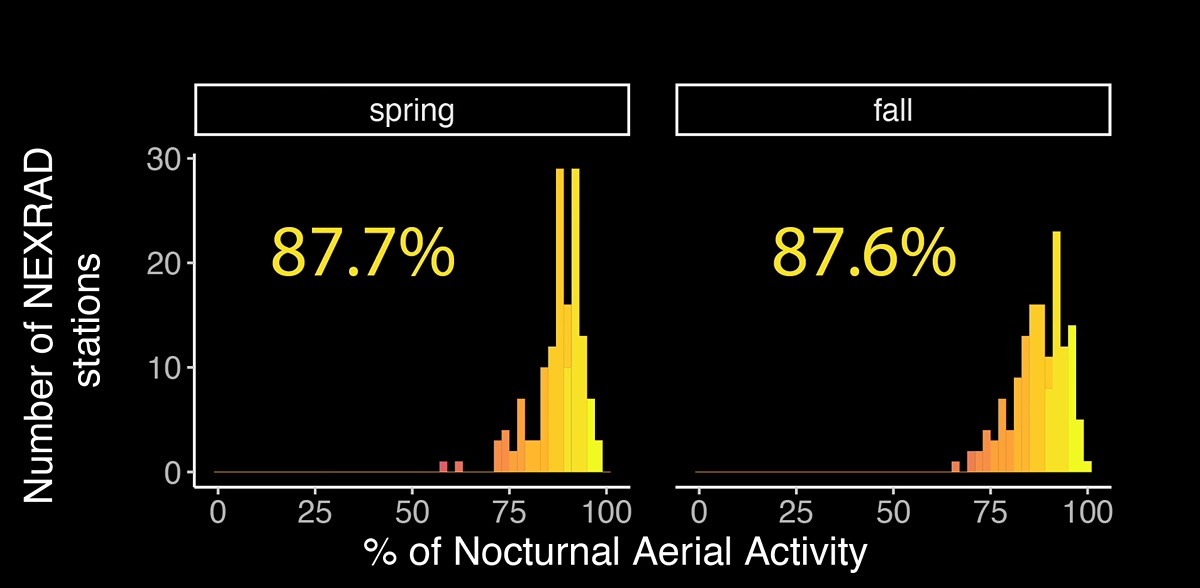

“These radar scans give us something we’ve never had before: a continental-scale view of how animals use the airspace over a full 24-hour day,” said lead author Silvia Giuntini, a postdoctoral scholar in the Environment Analysis and Management Unit at the University of Insubria in Italy. “We found that airspace use is overwhelmingly nocturnal. In both spring and autumn, 88% of movement occurred at night, with summer showing a more even split at 54% nocturnal.”

The team also determined that peak aerial activity typically occurred about four hours after local sunset in both spring and autumn. During these peak times, on average, half of the aerial movement was confined within a vertical band of 516 meters, starting around 355 meters above ground level.

“This study pushes the boundaries of how we think about habitats,” said Carolyn Burt, co-author and clinical assistant professor of teaching and learning in Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. “As we populate the sky with airplanes, wind turbines, drones and artificial light, understanding how wildlife uses this space becomes essential.”

“Bird migration is unusual because so many species migrate together,” Horton explained. “We can hear different species calling as they pass overhead at night, but radar can’t tell them apart. A natural next step is pairing these massive radar datasets with species-specific tools to understand how different animals share the habitat.”

Giuntini commented on the coexistence of species and the abundance of resources in the airspace.

“What is striking about airspace is that it may be one of the few habitats where competition doesn’t dominate ecological dynamics,” she said. “During flight, species appear to share a vast space, almost as if the sky were a nearly limitless resource, challenging how we traditionally think about ecosystems.”

A new view of the night sky

“To protect species that rely on the sky, we first need to understand how they use it,” Horton said. “Our work shows that the lower atmosphere isn’t empty — it’s a living, dynamic habitat, structured in ways we can now measure thanks to radar. Viewing the sky this way opens the door to new conservation strategies, better forecasting tools and a deeper appreciation for the life happening above us every night.”

This research was supported by NASA and the National Science Foundation.

About Purdue Agriculture

Purdue University’s College of Agriculture is one of the world’s leading colleges of agricultural, food, life and natural resource sciences. The college is committed to preparing students to make a difference in whatever careers they pursue; stretching the frontiers of science to discover solutions to some of our most pressing global, regional and local challenges; and, through Purdue Extension and other engagement programs, educating the people of Indiana, the nation and the world to improve their lives and livelihoods. To learn more about Purdue Agriculture, visit this site.

About Purdue University

Purdue University is a public research university leading with excellence at scale. Ranked among top 10 public universities in the United States, Purdue discovers, disseminates and deploys knowledge with a quality and at a scale second to none. More than 106,000 students study at Purdue across multiple campuses, locations and modalities, including more than 57,000 at our main campus locations in West Lafayette and Indianapolis. Committed to affordability and accessibility, Purdue’s main campus has frozen tuition 14 years in a row. See how Purdue never stops in the persistent pursuit of the next giant leap — including its integrated, comprehensive Indianapolis urban expansion; the Mitch Daniels School of Business; Purdue Computes; and the One Health initiative — at https://www.purdue.edu/president/strategic-initiatives.

Writer: Wendy Mayer, wendymayer@purdue.edu

Media contact: Devyn Ashlea Raver, draver@purdue.edu

Sources: Kyle Horton, kghorton@purdue.edu; Carolyn Burt, cburt@purdue.edu; Sylvia Giuntini, silvia.giuntini11@gmail.com

Agricultural Communications: Maureen Manier, mmanier@purdue.edu, 765-494-8415

Journalist Assets: Publication quality charts and images can be obtained at this, link