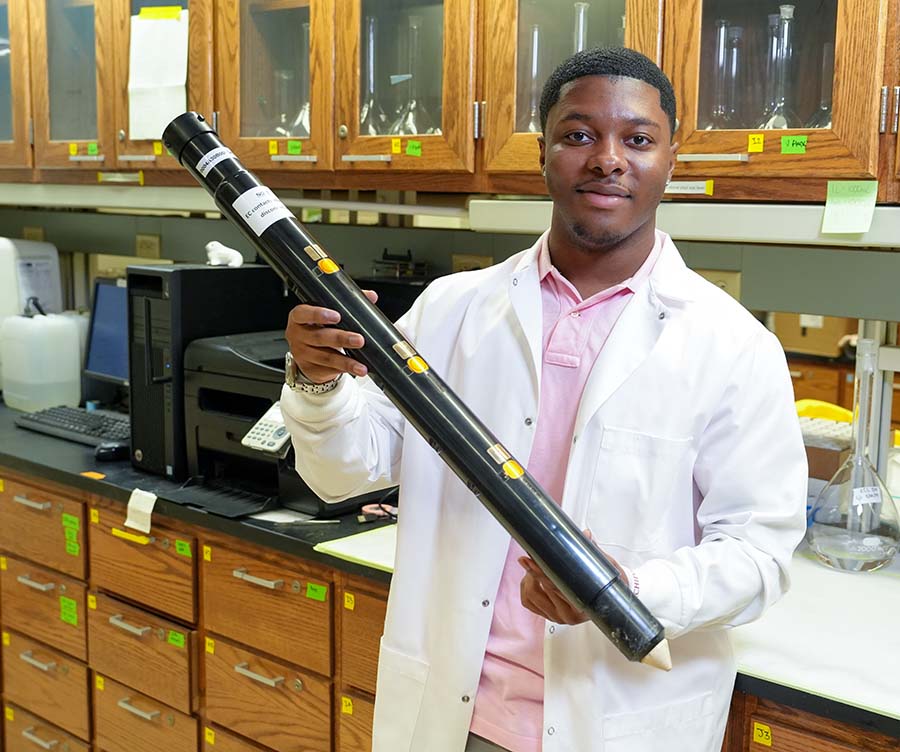

Jhacolby Williams - Graduate Ag Research Spotlight

The potential of this probe — to limit pollution at the source while also helping farmers not only save money but more optimally fertilize their fields — is pretty amazing.

- Jhacolby Williams, MS student, Department of Agronomy

The student

Although Jhacolby Williams hails from Greenville, Mississippi, growing up in the heart of the Delta wasn’t initially the source of his interest in soil. However, in a family oriented toward business management, “I was the oddball who wanted to go into science,” he says. When young Jhacolby begged for a dog, his mother said she’d consider it if he first demonstrated that he could take care of a plant. “Of course I thought that was insane,” he laughs. “But she got me a plant and I liked it. We eventually ended up getting a dog, but starting out with that plant sparked something.” Williams interned with a USDA Extension entomologist near his hometown before enrolling in agriculture and environmental science at Alcorn State University. Several of his undergraduate courses focused on soil science, and he completed the internship required for graduation at the Soil Health Institute in North Carolina. The soil scientists there “took me under their wing and influenced me to pursue higher education,” he says. One of his mentors had worked under Williams’ current Purdue advisor, Shalamar Armstrong, associate professor of soil conservation and management and director of the Soil Ecosystem Nutrient Dynamics (SEND) Lab. But Williams considered other graduate programs as well. “What really pulled me to Purdue last August was how my professor teaches,” he says. “He makes sure you have an understanding of what he’s asking you to do. He’s always available if you need clarification, but he’s not going to do it for you.”

The research

In the SEND Lab, Williams is evaluating the utility of a multifunction soil probe. “Normally one probe focuses on one particular soil dynamic,” he explains. But this probe combines sensors that measure — at different depths — nitrogen, soil moisture, electrical conductivity and phosphorus, with plans to later incorporate carbon dioxide. “My research asks, 'does it work?” he says. Williams hopes to contribute to technology that one day will give farmers an accurate and comprehensive depiction of their soil dynamics. “That would go a long way in limiting a lot of the excess fertilizer that’s prevalent in agriculture,” he says.

Opportunities

“I know a lot of master’s students hop onto a project, but I’m doing everything from scratch,” Williams says of his research. “I believe this is the first serious evaluation of the probe from an accredited university.” In addition to the novel project, he appreciates the lab’s supportive environment. He also has benefited from attending the annual Tri Societies Conference that brings together the international community of agronomy, crop and soil scientists. “It’s very eye-opening,” he says. And based on meeting Armstrong at the 2022 conference, “it’s a good networking opportunity as well,” the graduate student says.

Future plans

Williams expects to complete his two-year program in May 2025. He is unsure if he will continue on to a PhD but hopes his professional path may lead him back to the USDA. “In my internship with the USDA, I liked the art and science of it,” he says. His overarching goal is to contribute toward mitigating the effects of climate change. Outside of the lab, Williams plays sports or spends time in the gym. “I’m trying to be more health focused,” he says. He also enjoys time with friends and family and travel: “I love to hit the road.”