FNR Field Report: Tori Hongo

Students from Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources took their classroom knowledge to the field for summer internships and paid positions as well as research opportunities across the world, gaining valuable experience, hands-on training and career guidance. The FNR Field Reports series will offer updates from those individuals as summer positions and experiences draw to a close.

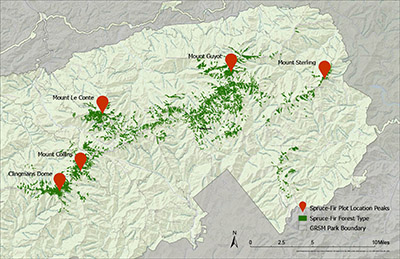

Tori Hongo spent the summer doing research on the spruce-fir forest in the Smoky Mountains as part of the field work component for her master’s project. Her work, under advisor Dr. Mike Jenkins, continues a long-term research project which began in 1990 following a balsam woolly adelgid invasion, which decimated 90 percent of the Fraser fir (Abies fraseri) in the area. The project involves sampling 37 spruce-fir plots across five mountain peaks, collecting data on trees and woody vegetation to measure Fraser fir regeneration efforts.

The summer in the Smokies was actually a coming home of sorts for Hongo, a Franklin, Tennessee, native, who spent two years working at Great Smoky Mountains National Park before arriving at Purdue in January 2022, acting as an intern with the Southeast Conservation Corps and then in a job with the Park Service doing vegetation monitoring.

“I had been there since 2020 and I knew at some point I wanted to get my masters but I was in no rush to do it,” Hongo explained. “Mike Jenkins was a vegetation ecologist in the Smokies and I actually was going to work with Cameron Dow, another student in his lab, doing some chestnut-oak work. I knew about him and he knew about me and he said, I have this spruce-fir project coming up in 2022. I had worked all around the park in different forest types. I knew the park pretty well, I like spruce-fir and the research sounded interesting, so the timing worked out.

“Being that it is a long-term research project that started in 1990, I thought I would love to add on to it and see those long-term changes in forest ecology, which is rare in a master’s project. It was great to be able to go back and build on the knowledge that I already had, but also to really dive deep into spruce-fir and really focus on that forest type and see so many different examples of what it looks like across the park. The Fraser fir are coming back and it is good to see it still thriving in that environment where it is supposed to be.”

The invasive balsam woody adelgid came into the area in the 1950s. By the 1980s, it had killed about 90 percent of the fir, which is one of the main overstory species at that high elevation. In 1990, 37 spruce-fir plots, measuring 20 meters by 20 meters, were set up across five peaks to be monitored every decade. The last sampling of the plots occurred in 2010, which presented some challenges due to wildlife and woody vegetation growth.

The invasive balsam woody adelgid came into the area in the 1950s. By the 1980s, it had killed about 90 percent of the fir, which is one of the main overstory species at that high elevation. In 1990, 37 spruce-fir plots, measuring 20 meters by 20 meters, were set up across five peaks to be monitored every decade. The last sampling of the plots occurred in 2010, which presented some challenges due to wildlife and woody vegetation growth.

“The bears and squirrels apparently love to chew on the PVC stakes and the aluminum tags. The squirrels love those tree tags, some were either chewed off or had so many teeth marks you couldn’t read them,” Hongo said. “A lot of the stakes and tags also were swallowed by the tree growth of six to 10 centimeters, which we were kind of surprised about. Even though we had GPS points for the center of the plots and hand drawn tree maps, it had been 12 years since someone's been to these plots, so we couldn't figure out some of the individual trees. It was a bit of a puzzle, but we sampled trees and then did sub-sampling of shrubs, seedlings, substrate and deadwood, and we also collected some soil samples. We took a lot of different measurements while we were in the field, because when they made this protocol in the 1990s, they didn't know what to expect with these changes, so you have to cover all of your bases and then see what may be significant in the long run.”

Due to the elevation and climate, conditions were soggy and slippery and the area is covered in fog much of the time. Many of the locations are remote and require several miles of hiking.

“We could just drive to some of the peaks like Clingmans Dome, which was very nice, but we did spend two weeks on Mount LeConte,” Hongo said. “We stayed in a bunkhouse, which was good, but it was a five and a half mile hike up there. We stayed a full week, hiked back down on Thursday, then came back up the next Monday and stayed another full week. There was propane gas, running water and a shower, but no electricity. It was cold and wet up there, which was kind of refreshing compared to the Tennessee summer that I’m used to. The weather cooperated pretty well, but then July had the most rain on record. It was fun slipping and sliding in the soggy spruce and fir.”

“We could just drive to some of the peaks like Clingmans Dome, which was very nice, but we did spend two weeks on Mount LeConte,” Hongo said. “We stayed in a bunkhouse, which was good, but it was a five and a half mile hike up there. We stayed a full week, hiked back down on Thursday, then came back up the next Monday and stayed another full week. There was propane gas, running water and a shower, but no electricity. It was cold and wet up there, which was kind of refreshing compared to the Tennessee summer that I’m used to. The weather cooperated pretty well, but then July had the most rain on record. It was fun slipping and sliding in the soggy spruce and fir.”

The field work lasted from May through the beginning of August and the team was able to complete 30 of the 37 plots, making their way to four of the five peaks. Each plot took approximately three to five hours to complete sampling.

“I knew it would be challenging to get to all these sites just because some of them are pretty remote and we were backpacking. I was leading a crew of some people that had never backpacked before, but it all turned out pretty well,” Hongo said. “When you have to hike five or more miles out to these plots to even get there, you have very minimal time to be in the plot doing the sampling. We could usually get a 20x20 plot done in three hours minimum, five hours max, depending on how many trees there were and how gnarly it was. It really depended on the place, and who we had. And also, if you were training someone new in that plot, it was going to take a lot longer, but you were also glad for their help. We always had new people coming in and helping, which was really good.”

Altogether, 23 people chipped in to help Hongo from field research assistants to park employees to family members during the summer or in September as she wrapped up fieldwork.

“I really got a lot of great people to help me out and I am super grateful for all of their help because we could not have done it without them,” Hongo emphasized. “I had a field tech who came from Pittsburgh, that was my Purdue field tech, and then we had the Park Service interns with vegetation monitoring like I did two years ago, and some of the Vegetation Management crew also helped out. I was glad that the people I worked with in the park were able to lend us their field crew so often, because that really helped out. My sister and one of my friends from high school even came to help. Once we were confident in the protocols and measuring all of the different things, we knew we could teach other people. It was good to have those teaching moments and also fun to see my interns take the reins and teach somebody else.

“To be with people who were super enthusiastic about field work, and could be laughing and having a good time, even if they're crawling through witch hobble and blackberry, not the most fun environment, and probably being soggy all day, was really great. There is always something to see and find and learn about, like cool mushrooms and salamanders and birds, so being surrounded by people who were interested and enjoyed that was fun.”

Photos from Tori Hongo's research in the Smoky Mountains (Clockwise from top left): Hongo and team backpacking on Mount LeConte; encountering a slug while measuring trees; Hiking Mount LeConte with advisor Mike Jenkins; taking in a sunset on Mount LeConte; Kuwahi (Clingmans Dome) showing living and standing dead firs; backpacking to Mount Guyot; a candid shot at the final plot on Mount Guyot; Tori tagging trees; a red cheeked salamander (Plethodon jordani); Tori using a hypsometer; Tori backpacking Mount LeConte

Photos from Tori Hongo's research in the Smoky Mountains (Clockwise from top left): Hongo and team backpacking on Mount LeConte; encountering a slug while measuring trees; Hiking Mount LeConte with advisor Mike Jenkins; taking in a sunset on Mount LeConte; Kuwahi (Clingmans Dome) showing living and standing dead firs; backpacking to Mount Guyot; a candid shot at the final plot on Mount Guyot; Tori tagging trees; a red cheeked salamander (Plethodon jordani); Tori using a hypsometer; Tori backpacking Mount LeConte Despite many hands helping with the field work, the group was stopped in its tracks in July when COVID-19 struck the researchers.

“That was a big challenge,” Hongo said. “We were in the flow of fieldwork, we had the protocol down and it kind of put a halt to our field work for a bit and made us take a step back and prioritize our health, both physical and mental. I think the people that you surround yourself with is important too. We all took care of each other and supported each other.

“You expect hiccups and changes to plans, but when we all got sick, we realized there were other things we could do besides hike up the mountains. We would just drive around the mountains. We did some blacklighting for moths and looked for salamanders. We could still do things, even if we weren’t hiking 10 miles up a mountain and doing field work. There is still so much to see and learn. It was a bit disappointing, but we had to take care of ourselves first and we realized that the trees would still be there whenever we got to them. Everyone stepped up when some of us couldn’t go out anymore.”

“You expect hiccups and changes to plans, but when we all got sick, we realized there were other things we could do besides hike up the mountains. We would just drive around the mountains. We did some blacklighting for moths and looked for salamanders. We could still do things, even if we weren’t hiking 10 miles up a mountain and doing field work. There is still so much to see and learn. It was a bit disappointing, but we had to take care of ourselves first and we realized that the trees would still be there whenever we got to them. Everyone stepped up when some of us couldn’t go out anymore.”

The illness made Hongo decide to postpone sampling on the last peak, Mount Guyot, where the final seven plots reside until September. Those sites are the most remote, requiring more than nine miles of hiking just to get to the Appalachian Trail shelter near the peak, with more than 5000-feet of elevation gain.

“I think we made the right decision not trying to squeeze it in at the beginning of August,” Hongo stated. “If something goes wrong, that is not the place you want to be having issues, so we said, let’s just postpone it and see how we are feeling then. That is how all of July was. I don’t know how I am going to feel tomorrow when I wake up, maybe I’ll be fine, maybe I won’t. It was the same with the weather. If the weather is good and everyone is feeling good, we can go do a plot. I think it made us live in the present and take things day by day. Field work makes you have to pay attention to the here and now.”

By postponing the field work, Hongo gained the assistance of her labmates in the Jenkins lab. Hongo and six others from Purdue and the Park Service made the trek up to Mount Guyot together Sept. 6 for a week long stay.

By postponing the field work, Hongo gained the assistance of her labmates in the Jenkins lab. Hongo and six others from Purdue and the Park Service made the trek up to Mount Guyot together Sept. 6 for a week long stay.

“The backpacking trip as a success,” Hongo said. “The team finished sampling the plots and returned a day early despite the storms and tough terrain. Wrapping up fieldwork was bittersweet, but there is still much work to be done with this project.”

Although the full results from data collection still need to be processed, a few observations from the field work stuck out to Hongo.

“I was surprised how fast these trees were growing and they look healthy,” Hongo said. “You could see how much the tree tags were swallowed, but a lot of these trees were in huge canopy gaps, so they had great conditions for growth and they were going for it. I was also surprised as we moved from peak to peak, how different those were. They are slightly different elevations and there are obviously some different environmental factors on each peak. The infestation moved from east to west through the park, so there were different time periods of infestations as well. That will be interesting when I look at the data to see if  that impacted it. Also, the understory was interesting to see. Some places were mossy and ferny, and then in some plots there would be a whole stand of so many fir packed together that no light is reaching the floor, so it is just deadwood and leaf litter and nothing green. It is really interesting that you get that much variability in different stages of regeneration.

that impacted it. Also, the understory was interesting to see. Some places were mossy and ferny, and then in some plots there would be a whole stand of so many fir packed together that no light is reaching the floor, so it is just deadwood and leaf litter and nothing green. It is really interesting that you get that much variability in different stages of regeneration.

“We also measured tree heights, which was something I had never done before. I’m not really sure what I am going to do with that data yet, but it was cool. Right now, a lot of these plots have super dominant spruce over a regenerating fir understory that is coming up into the canopy now. Some of those spruce trees are 80 centimeters DBH and 30 meters tall, and they are probably 200 years old. It was cool to see those dynamics happening as well. We had to measure random trees, but sometimes I would measure some of the big spruce just for fun, not to include it in the data, but just because I wanted to know how big they were.”

Due to the long-term nature of the study, Hongo had to collect data to follow previous research, but also had to decide data points of her own to add to guide the direction of her own work.

“I kind of knew what to expect, but it is so different looking at in on paper or at the numbers in a database versus getting out there in the field,” Hongo explained. “There are so many things you have to think about and decide on the spot in those field settings. It was definitely a challenge figuring out what they were doing last time, and I knew that was coming, but it made me want to take better notes and pay more attention to details in the field, so that the person who comes next will have all of that information before going out there. It helped me realize what a difference it would make if I took a few more minutes to write something down and be a better scientist, especially with some of the qualitative things.”

In addition to gathering data from the long-term spruce-fir plots, Hongo and her crew made it easier for future researchers by replacing chewed up PVC pipes with metal rebar to mark plot points and re-tagging trees.

In addition to gathering data from the long-term spruce-fir plots, Hongo and her crew made it easier for future researchers by replacing chewed up PVC pipes with metal rebar to mark plot points and re-tagging trees.

Time in class and in the field have Hongo excited to dig deeper into her findings.

“Last spring, I took a disturbance ecology course taught by Drs. Mike Jenkins and Mike Saunders that made me look at disturbances on a landscape level,” Hongo explained. “If the disturbance is an insect infestation like this one, it affects these trees individually and the spruce-fir forest on a landscape level, but the severity of the disturbance can be different in little patches. It was interesting to change my mindset on that. It was cool to see that a disturbance does not necessarily mean it is all devastating. That is one of the things I am excited about this long-term study, and I think the Park Service is excited to see the results of the study, to see how the spruce-fir forest is recovering. It is still a little early to know what we have, but I can’t wait to get into the data and analyze what we found.”

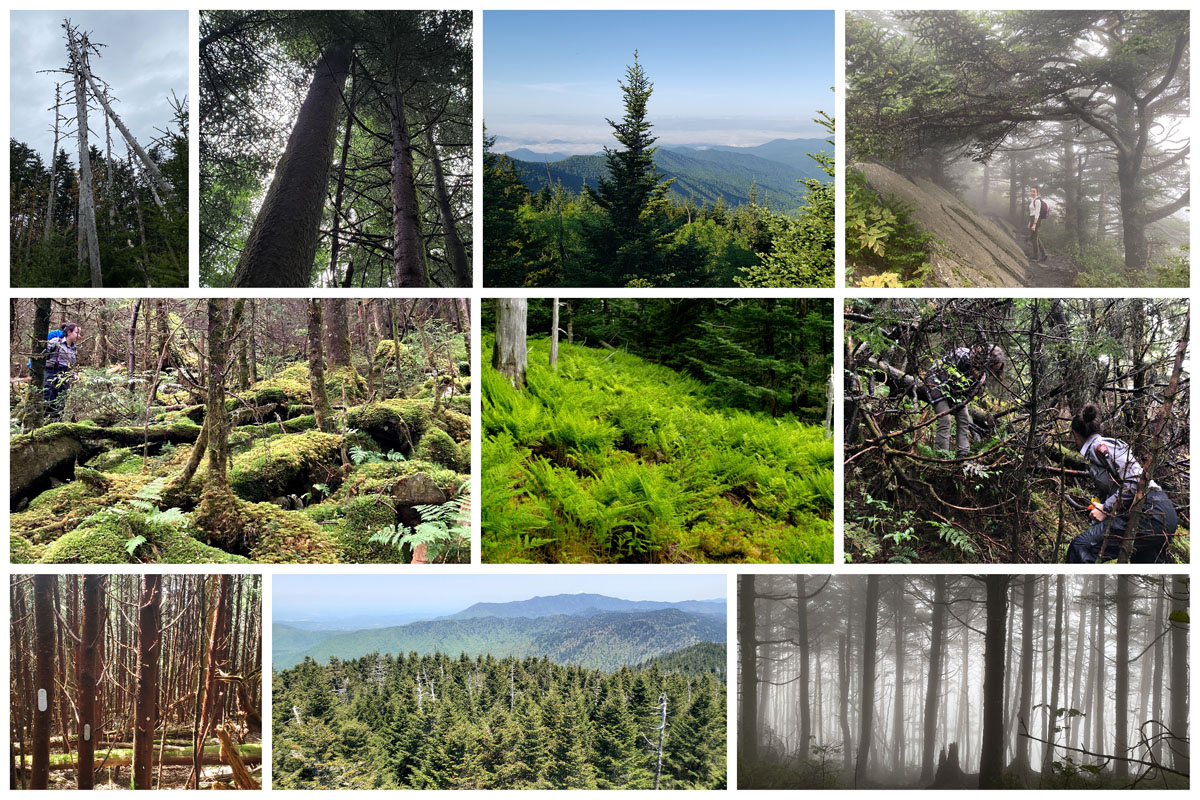

Photos of trees from Tori Hongo's research in the Smoky Mountains (Top row left to right): fir skeletons; red spruce (Picea rubens); Fraser fir (Abies fraseri); Tori on the Appalachian Trail with a Fraser fir; Second row (L to R): boulder field in the understory; fern understory; searching for the rebar marker in woody vegetation; bottom row (L to R): fir regeneration station - trees with tags; Clingmans Dome with living and standing dead firs; foggy day in the understory

Photos of trees from Tori Hongo's research in the Smoky Mountains (Top row left to right): fir skeletons; red spruce (Picea rubens); Fraser fir (Abies fraseri); Tori on the Appalachian Trail with a Fraser fir; Second row (L to R): boulder field in the understory; fern understory; searching for the rebar marker in woody vegetation; bottom row (L to R): fir regeneration station - trees with tags; Clingmans Dome with living and standing dead firs; foggy day in the understory