FNR Graduate Student Spotlight: Meredith Scherer

“Ordinary people with commitment can make an extraordinary impact on their world” – John C. Maxwell.

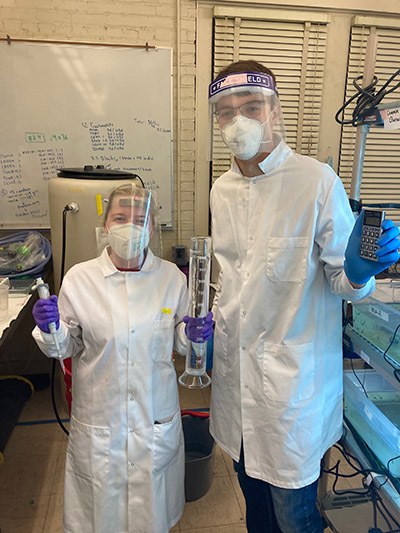

Whether it is the work she is doing in the lab to understand the impacts of per- and polyfluoroalkylated chemicals, or forever chemicals, on wildlife and the environment or the many lives she has changed through her work building countless homes with the Purdue chapter of Habitat for Humanity, there is no doubt that master’s student Meredith Scherer is making an impact.

chemicals, or forever chemicals, on wildlife and the environment or the many lives she has changed through her work building countless homes with the Purdue chapter of Habitat for Humanity, there is no doubt that master’s student Meredith Scherer is making an impact.

Scherer has been a member of the Purdue chapter Habitat board for the last six years and served as its president last year. Her Saturdays volunteering in the Lafayette community and building homes for people who need them fulfills Scherer in many ways.

“I love getting to directly interact with the people I am helping and also working with the students and bringing them out into Lafayette and helping them feel civically engaged,” Scherer explained. “You can feel like you are on a little island at Purdue and really insulated, but it is great to see what’s actually going on in the real world. For me, it is the hands-on part of the experience. You go every Saturday and you see that really tangible result. You see that the wall got painted, the trench got dug or whatever task you are doing that day, and you see that you made such a difference. It’s a nice contrast to how I feel sometimes with the science, where you sit down and type for hours and, while you added a little bit to your paper, it doesn’t always feel like you accomplished something.”

That isn’t to say her work investigating impacts of salt and pathogens on common water fleas (Daphnia dentifera) and of PFAS on the African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis), isn’t impactful or fulfilling.

“It is so relevant,” Scherer said. “I really like how I’ve started to hear more about PFAS in the news over the last two years I’ve been in the lab. I’ve started to see people recognize that it is all around us and it has been really exciting to see that direct impact.

“PFAS stands for per- and polyfluoroalkylated substances, a class of chemicals that has many, many different types of chemicals within it, and these chemicals are highly used in industry, and even in our homes. They have a suite of super desirable properties, including heat resistance and water resistance, but the mainstay of PFAS is that they have this carbon fluorine bond, which is really strong and makes it really persistent, so it will not degrade, even if you want it to. That means that it remains in the environment, and it remains in our bodies for a very long time. It's found in so many consumer products like the lining on Tupperware, in non-stick pans and even in a rain coat. You are always being exposed to it, and that is why we need to know what it's doing.”

Involvement in science and nature started for Scherer as a child at a “somewhat crunchy elementary school” in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, suburbs, that was very outdoor based.

school” in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, suburbs, that was very outdoor based.

“We had outdoor classrooms and spent a lot of time walking down at a local creek next to our school,” Scherer said. “I was definitely the kid flipping over the rocks in the creek. We would go out with little cups so we could catch what was under the rock, crayfish or sometimes little water snakes. There was always something different to see. And then, when the seasons changed, different animals came out. It was always interesting to see what was out there. We had some days where the whole grade would walk down to the creek and you would have to bring your creek outfit and then you’d have all of your muddy boots outside of the classroom. It was nice because it was sort of a rural area and we were able to spend so much time outdoors. It was very lucky to have that type of exposure to the outdoors and that is what initially sparked my interest in science and it has just sort of grown from there.”

That interest and enjoyment of science led Scherer to delve into biology and later AP Biology in high school. A love of animals and the idea of potentially helping animals led Scherer to apply to Purdue, due to its highly-rated veterinary school.

“When I got into Purdue for biology, I knew that was where I wanted to go and what I wanted to do,” Scherer said. “During my first semester I learned a little bit about vet school through some seminars they had and realized it wasn’t going to be for me. So, I stuck with biology and ended up majoring in the ecology branch of biology at Purdue. While I was doing that, I was in a bunch of different labs: botany, chemical and landscape ecology labs. I decided that I liked being in those plant labs, but mostly for the glimpse into lab life that I got – seeing the structure of how a lab functions and the hierarchy, planning experiments and the scientific method – but I didn’t love working with plants.

“I wanted something a bit more charismatic and engaging, so that is why I transitioned over to the aquatic disease ecology lab with Dr. Searle. I had so much fun and I really enjoyed working on projects with frogs and invertebrates and a lot of water-based studies. I understood why people liked being in the lab all of the time and thinking very deeply about science. I really liked the way that lab functioned and it connected me to where I am now.”

disease ecology lab with Dr. Searle. I had so much fun and I really enjoyed working on projects with frogs and invertebrates and a lot of water-based studies. I understood why people liked being in the lab all of the time and thinking very deeply about science. I really liked the way that lab functioned and it connected me to where I am now.”

In the Searle lab, Scherer assisted graduate students with their projects, but also completed an honors thesis of her own as well because she wanted to “have additional ownership of it.” The project looked at the abiotic stressor of a high or low salinity treatment and combining that with the presence or absence of a fungal pathogen. She tested those two stressors on 12 different clones of Daphnia to see if any of the clones had a resistance to the combination, or whether all clones were equally susceptible or some were better with the pathogen or with the salt.

“I had worked on plenty of other research projects and I felt like I had learned enough that I could have a little project, put it together by myself and analyze it and have that complete unit at the end,” Scherer said. “Dr. Searle was nice enough to work with me on it and I ended up doing a multiple stressors project, which was really cool thinking about all the different ways that those two pieces could combine.

“We ended up mostly seeing that there was no difference in the effects of the stressors on the clones, which was still an interesting result because most people do treat the clones of Daphnia to be essentially the same. They are all Daphnia dentifera, but there are a million lakes across the United States, so that is about a million different clones. It is important to know there isn’t a ton of difference between them.”

While working in Dr. Searle’s aquatic disease ecology lab and considering graduate school, Scherer heard about the ecotoxicology group in Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue.

“I found Dr. Sepúlveda and I really liked the type of work that she was doing,” Scherer recalled. “I thought it was really interesting and working with PFAS is pretty bonkers, because no one really knows what they are. It is really interesting to get to be on the leading edge and get to have such a hand in it.”

was really interesting and working with PFAS is pretty bonkers, because no one really knows what they are. It is really interesting to get to be on the leading edge and get to have such a hand in it.”

Scherer hit the ground running once she joined the lab, assisting an undergraduate student through the Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURF) in completing a study, which resulted in a poster titled “Is Toxicity of Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid Mediated by Salinity in estuarine Larvae and Embryos?” and a paper that is currently under review. The poster won Scherer first place among graduate students in the basic science category at the Joint Aquatic Sciences Meeting in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in May 2022.

“The study ended up being a little bit ambitious for the undergrad research program, so another graduate student and I helped the student with the second portion of it to get it across the finish line,” Scherer explained. “It is not going to be in my thesis, but it was great to start in the lab and immediately get to join in on a project.”

Being in Sepulveda’s ecotoxicology lab has pushed Scherer to expand the breadth of her research and helped her network with others in the field.

“Dr. Sepulveda is definitely a very supportive mentor,” Scherer said. “She really has high hopes for you and pushes you to achieve them. She wouldn’t make you do something that you couldn’t do, but she is always there encouraging students that they could probably do a little more by saying what if we added this interesting part to your project? She’s also so well connected in the world of PFAS that she always has a potential person you could chat with or that can help you with a portion of your project. In that way, you can get so much more done because you aren’t having to learn everything yourself.”

Scherer’s thesis will include a chapter based on a large study that the entire lab participated in, which looked at generating toxicity reference values for PFOA (Perfluorooctanoic Acid). PFOA is a terminal degradation product, or the smallest pieces that many PFAS break down into.

“PFOA won’t degrade any more and because of that, it is what we see in the environment most often,” Scherer explained. “Since it is so common, it is good to know what it is doing. We exposed tadpoles, from an early life stage to the time when their tails are totally resorbed, and sampled them throughout and took weight and length measurements to see how the PFOA affected them. Interestingly, there were basically no results, which tells us that Xenopus laevis are really insensitive to PFOA. This sort of non-result is still a result, because it tells you that if you want to study toxicity of PFOA that you shouldn’t use Xenopus, you should use a different organism.”

The second chapter of Scherer’s thesis looks at Toxicokinetic modeling of PFAS, or how the toxin interacts with the body.

“If you have a tadpole and you put it in water that is dosed with a high concentration of PFOA, for example, then you'll start to see the tadpole accumulate the chemical, and then, at some point, it will reach a steady state, where it is as full as it can get of the chemical. Then, if you take the tadpole and put it in clean water without any of the chemical in it, it will start to depurate the chemical, which is losing it from its system essentially through urination or diffusion through the skin. What I'm doing right now is modeling that curve using math.

“Toxicokinetic modeling is an important thing we use in risk assessments. If there were to be a chemical spill and animals were exposed to 10 minutes versus two weeks, they would take up a much different amount of the chemical into their body. So, it would help to know what the internal dose might be to the animal or essentially how severe it would be. That is what the modeling will do.”

Scherer will defend her thesis in the coming weeks and graduate in May before heading out into the career world. She will begin a fellowship with the Environmental Protection Agency this summer. In the EPA In Vitro Disposition Modeling and Data Analysis Fellowship, Scherer will continue to work on toxicokinetic modeling and data analysis.

Wherever her career may take her, one thing is for sure, Scherer will continue to make an impact on the world both in the lab and beyond.

Meredith Scherer holding a large-mouth bass she caught during field sampling; Meredith and labmate Anna doing fieldwork in Robinson, Illinois; Meredith and chainsaw training with fellow master's students Meghan Ciupak and Anna; Meredith with a snake during field sampling

Meredith Scherer holding a large-mouth bass she caught during field sampling; Meredith and labmate Anna doing fieldwork in Robinson, Illinois; Meredith and chainsaw training with fellow master's students Meghan Ciupak and Anna; Meredith with a snake during field sampling