FNR Field Report: Alumni Amanda Herbert, Bill Beatty Research Pacific Walruses in Alaska

Bill Beatty, a 2012 PhD alumnus and current research wildlife biologist for the U.S. Geological Survey’s Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, and Amanda Herbert, a 2023 wildlife alumna, worked together researching Pacific walruses on a ship in northern Alaska last summer.

Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, and Amanda Herbert, a 2023 wildlife alumna, worked together researching Pacific walruses on a ship in northern Alaska last summer.

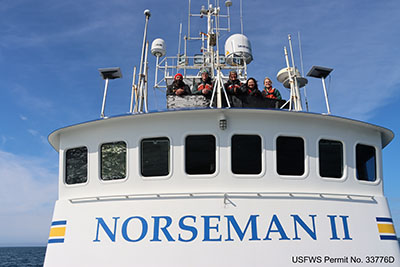

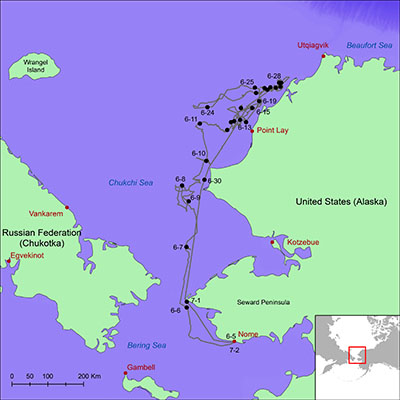

The pair were among the 21 individuals that lived and worked on a chartered research vessel called the Norseman 2 in the Chukchi Sea from June 5 to July 2. Beatty led the research team, while Herbert worked as an observer for the USGS on the project. The collaborative research with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service aims to quantify the population trend of Pacific walruses over time.

When they weren’t observing groups of walruses, researchers lived, ate and slept on the 115-foot-long research vessel. The Norseman 2 was initially built as a commercial king crab boat, but was converted into a privately owned and operated research vessel in 2010. A crew of five – the captain, the first mate, the deck boss, the cook and a deck hand – handled the day-to-day operations of the ship. The 16-member research team, some from the USGS and some from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, rounded out the ship’s residents.

The environment, the work and her colleagues all made an impression on Herbert.

“It was amazing. It was the coolest experience of my life. I liked being out there and seeing so much wildlife and being in a different setting than I am used to,” Herbert said. “Everyone was so welcoming. The researchers were very knowledgeable and they helped me learn a lot. The opportunity to work in Alaska, especially the Arctic, and the fact that it could help me towards my career goals of working with large mammals really stood out about the position. We definitely put in long hours, but I loved what I was doing, so it didn’t even feel like work, which was the best part.”

The Journey To Alaska

Beatty did his doctoral research at Purdue on the ecology of Virginia opossums in Indiana, working under Dr. Gene Rhodes. He published three papers from his dissertation: Genetic structure of a Virginia opossum (iDidelphis virginianai) population inhabiting a fragmented agricultural ecosystem; Habitat selection by a generalist mesopredator near its historical range boundary; Influence of habitat attributes on density of Virginia opossums in agricultural ecosystems.

After graduation in 2012, he worked as a post-doctoral researcher for the Missouri Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit for two years, studying water fowl movement and spatial use. Beatty then moved into a short-term research wildlife biologist position with the USGS Alaska Science Center in Anchorage from 2014-16. He then worked for five years as a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in marine mammals management. Since 2021, Beatty has been back at the USGS, working as a research wildlife biologist at the Upper Midwest Environmental Services Center, based in Wisconsin, and the Alaska Science Center.

Wildlife Research Unit for two years, studying water fowl movement and spatial use. Beatty then moved into a short-term research wildlife biologist position with the USGS Alaska Science Center in Anchorage from 2014-16. He then worked for five years as a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in marine mammals management. Since 2021, Beatty has been back at the USGS, working as a research wildlife biologist at the Upper Midwest Environmental Services Center, based in Wisconsin, and the Alaska Science Center.

“My experience as a postdoc in the Missouri Co-Op Unit was my first exposure to USGS science in a real way,” Beatty said. “It is important to note that the U.S. Geological Society is a science agency. We don’t do anything when it comes to the management of or policy for wildlife science. We simply provide the science for other agencies to use. It has been quite the whirlwind, but walruses have mostly been my focus since my post-doc. I also have done a little bit of sea otter work.”

Herbert, who graduated in May 2023 with a degree in wildlife, was involved in the Purdue Student Chapter of The Wildlife Society and the Society of American Foresters during her time in FNR.

“My time in FNR was amazing,” Herbert said. “My experience at Summer Practicum as a student was amazing and was obviously the highlight of my time at Purdue. I got to meet so many peers who I’d never really had a chance to interact with. It was my first real introduction to the field, and it was great because it showed me that I was in the right field and the right major. Being a teaching assistant at Practicum was nice because I was able to use the experience that I had the previous year and step up and teach other students. I wasn’t only teaching them, but I was also furthering my own experience and being more hands on. Being able to work with the professors, communicating with them months in advance, trying to get together lists of everything and putting everything together for the activities was a great time. We put in 60 hours a week at least, but it definitely prepared me for the field season.”

Herbert also was involved in undergraduate research in Dr. Pat Zollner’s lab, working with PhD student Marian Wahl on black and turkey vulture consumption patterns. After initially doing data collection for Wahl and looking through photos and scoring them, Herbert took the initiative to create her own original research project looking at black and turkey vulture competitive interactions while scavenging.

“Amanda was an exceptional undergraduate researcher in my lab,” Zollner said. “This is reflected in her productivity in terms of being a coauthor on a paper led by Marian Wahl and also in her developing her own ideas while working with that data that led to a second publication that she is the first author on. That second paper is now in review at the Journal of Raptor Research. Beyond productivity, the level of commitment needed to produce this kind of work while carrying a busy course load as a senior wildlife major is indicative of exceptional dedication and passion for wildlife ecology. “

productivity in terms of being a coauthor on a paper led by Marian Wahl and also in her developing her own ideas while working with that data that led to a second publication that she is the first author on. That second paper is now in review at the Journal of Raptor Research. Beyond productivity, the level of commitment needed to produce this kind of work while carrying a busy course load as a senior wildlife major is indicative of exceptional dedication and passion for wildlife ecology. “

Herbert also spent a month studying abroad in Tanzania in a large carnivore program as part of the School for Field Studies, which focused on the behavior and ecology of large carnivores.

Herbert first met Beatty at The Wildlife Society conference in Spokane, Washington, in the fall of 2022, where she was presenting her research with Wahl. Herbert expressed an interest in the upcoming research opportunity in Alaska at that time, but still had to go through a competitive process in order be hired onto the ship’s research crew as an observer for the USGS research cruise.

Beatty said two things stuck out about Herbert over other candidates.

“I taught a module of small mammal trapping with Jim Beasley at Practicum when I was a grad student, so I know that Purdue asks a lot of the undergraduate TAs, from working with different people, prepping for the modules in the field, and working for long hours with little to no thank yous,” Beatty said. “Amanda also had experience looking at and analyzing photos through her research working with Pat Zollner. The application process was a very competitive situation, but she had those experiences that set her apart and she interviewed very well.”

The Research in Alaska

The Pacific walrus is special among marine mammals in that it is managed by the United States Department of the Interior. The species is designated as a trust species under the Department of the Interior alongside polar bears, sea otters and manatees. Each project regarding Pacific walruses, which are a species of conservation concern, requires a robust permitting process, so every aspect of the research is well established.

Pacific walruses have been an important subsistence resource for Alaska Native communities and natives in Russia for time immemorial. Walruses dive to the sea floor to get their food. They like to rest on sea ice over shallow water between foraging bouts. Beatty explained that the Arctic basin is too deep for the species, so the impact of sea ice loss in continental shelf water areas of the Arctic is of great concern for the current Pacific walrus population and that of the future, making this summer’s population research both timely and important.

After departing Nome, Alaska, the research vessel operated 24 hours a day, seven days a week for a month. The research schedule required the team to be prepared to work day or night, whenever the ship might approach a group of walruses. Once a group of walruses was spotted down wind, Beatty called for the five-member research team to assemble on the flying bridge of the ship, an outdoor platform above the wheelhouse. Observers then looked at each group of walruses, using an established method to assign each animal in the group into an age and sex category.

The method, which was developed by a walrus biologist in the 1980s, allows researchers to look at the relative length of the tusk compared to the width or the depth of the snout of the walrus to assign age classes from calf to 1, 2, 3, 4-5, 6-9, 10-15 and over 15 years old. For example, Beatty explained, if the tusks are just less than the depth of the snout, that animal is a 4 to 5 year old. Whereas if the tusk is about 1.1 times the depth of the snout and the head is smaller and not as blocky, that is a 6 to 9-year-old female.

“We probably see thousands of walruses over the course of the project, so you get up to speed pretty quickly on the method,” Beatty explained. “We went through training with everyone on the crew in early May and again on the ship before we started work. There is also lots of on-the-job training.”

Beyond the intricacies of identifying the tusk size and head shape for each walrus, there are other challenges involved. Walruses often assemble in large groups and may be laying on top of one another, obstructing researchers’ views, and may not be fully visible until they are diving off the ice into the water.

challenges involved. Walruses often assemble in large groups and may be laying on top of one another, obstructing researchers’ views, and may not be fully visible until they are diving off the ice into the water.

“Sometimes we would be waiting for 20 minutes to try and see all of them in a group,” Herbert said. “They didn’t care that we were there, so they didn’t look up or anything. We were like, can you please move your head just a little bit so I can get the slightest peek?”

At times, there may be walruses on both sides of the ship, so researchers divide and conquer with some observing on the starboard side and others on the port side. Groups of animals may also vary in count. For groups of 10 or more, researchers work as a full team to ensure all animals are properly identified. For smaller groups, researchers observe and may record the data alone or in pairs.

The wind, weather and general environment determine how much time researchers have to document each group.

“Sometimes you can get really close and sometimes you can’t,” Beatty said. “Sometimes you have to start making the calls from 200 or 300 meters away. Inevitably, they will all go into the water eventually when the ship is approaching them. They may not smell the ship, but they will see it. Sometimes they calmly go into the water, and sometimes they aren’t calm. How they behave also is determined by other animals around them.”

In addition to her work with the USGS, Herbert did rotations with the Fish and Wildlife Service, collecting samples through the use of a crossbow and biopsy darts.

“I really enjoyed being able to experience both sides of the research,” Herbert explained. “It didn’t feel like there was any real difference, because we were all working so closely together. I would be up on top of the main boat doing age structure surveys for USGS and then 30 minutes later I would be on a rotation with Fish and Wildlife, going out on a little pontoon boat to collect samples.

“While we were out there, we were able to work with Alaska Native hunters and get a different perspective than what we’re used to with Western science. It was nice being able to talk to them and see how they worked out on the sea ice and experience something different than what I have learned in classes, traditional ecological knowledge. I was able to get a different perspective on strategies that are used to get samples. To be able to actually use those strategies and know that the samples we obtained can influence management decisions in the future made me feel like I was doing something very valuable.”

Herbert not only learned from the hunters she worked with but also the other scientists on the boat.

“I was so excited going into it because I got to meet all of these different people with different stories of where they have been and where they are now,” Herbert shared. “At one point, Bill pointed out a woman named Erin who worked as the threatened and endangered species biologist for Alaska’s Fish and Wildlife Service. She was probably the most important person on the boat and the fact that I was able to work with somebody with that job and title right out of graduation was amazing. I learned so much from all of them. It was definitely scary at first, but once I got used to everything, I felt like I was good at what I was doing and I wasn’t worried anymore.”

Overall, Beatty was impressed by Herbert’s growth throughout the project.

“Amanda was the youngest and by far had the least amount of experience of all of the researchers on the crew,” Beatty noted. “But, once she got comfortable, she came out of her shell pretty quickly and by the end she had just as much confidence as all of the other people on the crew.”

After studying large mammals in Tanzania and working with Pacific walruses in Alaska, who knows what is next for Herbert. She has an interest in continuing to work with large mammals and exploring the topic of human-wildlife conflict as well as traveling.

For now, she is working as a post-construction mortality and monitoring technician for Atwell, an environmental consulting firm. In that role, she is looking at bird and bat mortality from wind turbines on a wind farm.

Now that her research publications have been submitted, Herbert is preparing for her next chapter, whether it be graduate school or permanent employment. Regardless of where life takes her, she will be ready for the next adventure.

“The biggest piece of advice I would give is to be open and willing to say yes to essentially all experiences, as long as they are safe and won’t get you in trouble, etc.,” Herbert said. “That is how I got started down this path. I met Marian Wahl during small mammals week at Practicum and she asked if anyone was interested in looking through thousands of photos of vultures and recording data for her. I said yes, I would love to, even though I was sure it might get boring, and that started the rest of everything. If I hadn’t done that, I wouldn’t have been able to go to The Wildlife Society Conference and I wouldn’t have been able to meet Bill and go on this amazing adventure. Be open to new opportunities, even if you think you know something. There is always something that you can take away from an experience.”