Dr. Jacob Goheen Named 2024 FNR Distinguished Alumni Award Recipient

Dr. Jacob Goheen, who received his master’s degree from Purdue in 2002, has contributed to the education of students, professionals and fellow scientists both domestically and internationally through teaching, research and outreach efforts.

For his work, FNR is proud to recognize him with the FNR Distinguished Alumni Award, which recognizes alumni for demonstrating a record of outstanding accomplishments, having made significant contributions to his/her profession or society in general and exhibiting high potential for future professional growth.

Goheen’s award-winning ecological and conservation research, through professorships at the University of British Columbia and the University of Wyoming and now through Iowa State University, has resulted in more than 100 peer-reviewed articles, but his impact has been felt well beyond the research community. He is devoted to training the next generation of leaders in wildlife science and conservation. His former students have gone on to become leaders in academia, non-government organizations and wildlife management agencies across the globe, including standout scientists like Dr. Abdullahi Hussein Ali and Dr. Caroline Ng’weno, who have been vital in the persistence of endangered species and alternative management techniques in Africa. Goheen partners with the National Museums of Kenya to provide internship opportunities for aspiring African conservation biologists. In addition, he has worked with colleagues in the American Society of Mammalogists to establish the African Research Fellowship, which provides funding to African scientists working on the ecology, conservation and evolution of African mammals. He also has contributed to the wildlife field as a whole through several board and publications positions.

“I was quite struck by this award and it came as a real surprise,” Goheen said. “I know several of the other recipients well, and am honored that folks found me sufficiently deserving for nomination into that same category.”

A life in wildlife began with a childhood outdoors, catching turtles, snakes and frogs and placing them in the window wells of his parents’ home in Topeka, Kansas, to keep as pets.

window wells of his parents’ home in Topeka, Kansas, to keep as pets.

“My friends and I were really into reptiles and amphibians growing up, in part because you could go out and see them, catch them and then keep them for a while and observe their behavior,” Goheen explained. “Since that time, I have become more interested in mammals and mammal ecology, but for me, herps were where it was at initially. Going to a ditch or little pond in the middle of summer, there were tadpoles everywhere and, if you were lucky, you might stumble upon a water snake or garter snake. One of my first memories was finding a three-toed box turtle. At the time, there weren’t many reports of those in Shawnee County; they were mostly ornate and eastern box turtles. So I grabbed this box turtle and put it in the window well. The next day, it was laying eggs and my mind was blown by that. That was pretty cool.”

Time spent on his maternal grandparents’ farm and at the local zoo with his parents also shaped Goheen’s experiences with nature. Three-week short courses in herpetology and aquatic biology at the University of Kansas, just 30 minutes from his home, also increased his knowledge. He also really enjoyed looking at field guides as a child.

“In grade school, they say that you can be anything you want when you grow up, so I always said I wanted to be a Wookie. But when I was told I couldn’t do that, I said, well, then I want to do something with animals,” Goheen said. “I wanted to be like the people on TV that you see on Animal Planet or National Geographic. So, in an abstract sense, I knew that there were people on Earth who did those things. It probably wasn’t until I got to my undergrad that I was like, there really are people who do those things and you can train to do those things. That is when it became a bit more real.”

Goheen’s training began at Kansas State University, where he majored in wildlife biology. Although a clear vision for his future career wasn’t yet clear, he knew that he didn’t want to be a vet, a zookeeper or a game warden. But, a mammalogy class his sophomore year changed everything.

“Both because of my advisors (Don Kaufman and Glennis Kaufman) and the TAs (Brock McMillan and Ray Matlack) in that class, I wound up thinking that what these folks do is exactly what I want to do,” Goheen recalled. “They were extremely good mentors that provided guidance without babying me too much. They also recommended Dr. Rob Swihart at Purdue as a graduate advisor. They had known each other through the American Society of Mammalogists and thought we would make a good match, and we did.”

Matlack) in that class, I wound up thinking that what these folks do is exactly what I want to do,” Goheen recalled. “They were extremely good mentors that provided guidance without babying me too much. They also recommended Dr. Rob Swihart at Purdue as a graduate advisor. They had known each other through the American Society of Mammalogists and thought we would make a good match, and we did.”

Once at Purdue as a master’s student, Goheen worked on the geographic range expansion of red squirrels. Red squirrels had been moving their range southward from the Great Lakes Region into Indiana and the rest of the Central Hardwood Forest Region.

“It was a really intriguing set of questions because they have all of these adaptations and behaviors and morphologies for living in coniferous forests. So we asked how they do it in mostly deciduous forests,” Goheen said. “Do they still store their food in one central location and defend it aggressively like they do with pine and spruce cones? How do they eke out a living alongside fox squirrels and gray squirrels? How quickly are they moving southwards? Are they having an effect on tree regeneration?

“It was a fantastic combination of things for me in that Rob, on the one hand, knew where the cool questions were, but, on the other hand, he gave me enough rope to let me think that I discovered them on my own. We started as student/mentor and I now consider him to be a very good friend. We really hit it off. He was a perfect blend of a hands on and hands off advisor.”

In addition to the research and mentorship, Goheen said he truly learned to "do science" at Purdue.

“There is a difference between being a consumer of facts and creating your own facts through research and I learned to do that at Purdue,” Goheen shared. “I was in the field 10 months out of the year. It was a lot of work, but it was always gratifying and sometimes even fun. But, on the days when it wasn’t fun and it got mundane, I tried to keep the bigger picture in mind: I need to this because what we are going to learn from this when it’s finished. That kept me going. I learned how the scientific process works and how to be a contributor to science. I learned how to multitask and juggle things. And, just by watching Rob and other faculty, grad students and scientists in FNR, I learned what makes a good collaboration.”

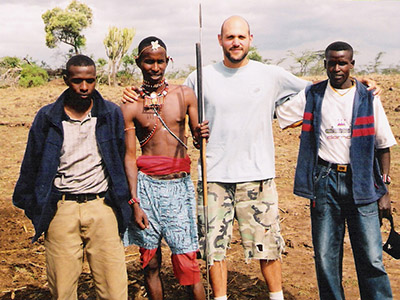

Before heading off to the University of New Mexico for his PhD, Goheen worked with a friend and collaborator in East Africa for six months, an experience that would alter the rest of his research and professional life.

collaborator in East Africa for six months, an experience that would alter the rest of his research and professional life.

The six-month stint in Africa was a long time coming. It all began when Goheen was an undergraduate at K-State and applied for the Research Experience for Undergraduates program through the National Science Foundation. His senior year, his third time applying, he earned a spot at the Institute of Ecosystem Studies (now the Cary Institute) in New York, working on a project with Drs. Ken Schmidt and Rick Ostfeld. While there, Goheen was exposed to the work being done in Kenya by Dr. Felicia Keesing, the significant other of one of his mentors at the Institute, and was amazed by her work.

“My mind was blown by the work that she was doing,” Goheen exclaimed. “She was very generous and a very thoughtful advisor to me there and allowed me to work in her study system. I always had that on my radar after that REU experience. Two to three times a year during my master’s at Purdue, I would email her and ask if I could go be an independent researcher with her in Kenya and she would say get back to me in six months. That happened for three years, then at the end of the third year, I think I just wore her down, so she very generously agreed to pay for a six-month trip to go out there. So, after finishing up at Purdue, I went to Kenya and was floored by everything that I saw.”

As an independent researcher and EPA STAR Fellow, Goheen found his passion.

“During that interim period between my master’s and PhD, I really fell in love with wildlife ecology in Kenya,” Goheen explained. “One reason for that is that everything out there was quite visible, very conspicuous, and that was very helpful for me to be able to go out and see things. It is very in your face and that resonated with me in a way that few other things had. I left Kenya thinking, wow, there are so many ecological questions for which we don’t have a great sense for their answers.

“Working in ecosystems in the U.S., I’d have a question, look into it and discover that 30 people had the same question and there were a hundred papers published on it. On one hand that was encouraging because it signals that you are barking up the right tree. But, on the other hand, there are a lot of people playing in the same intellectual sandbox. In Kenya, for better or worse, it was the opposite. It seemed like there was a lot of open, fertile intellectual ground. If I had a question, chances were that I was one of only a small number of people to have had that question. It was incredible.”

same question and there were a hundred papers published on it. On one hand that was encouraging because it signals that you are barking up the right tree. But, on the other hand, there are a lot of people playing in the same intellectual sandbox. In Kenya, for better or worse, it was the opposite. It seemed like there was a lot of open, fertile intellectual ground. If I had a question, chances were that I was one of only a small number of people to have had that question. It was incredible.”

While the charismatic and eye-opening ecosystem in Kenya had captured his heart and intellectual attention, PhD studies awaited at New Mexico, where Goheen would work with Dr. Jim Brown on an ongoing, long-term project looking at the community dynamics of kangaroo rats and other rodents.

“Because of that experience, I spent the first year or two at New Mexico trying to get back to Kenya and I eventually did get a few grants funded, but New Mexico was great,” Goheen said. “The first year or two I was working on Jim’s famous project and I learned from that the level of dedication and creativity you have to have to keep working in the same system and have continuous insights. But, I knew I couldn’t do that work better than my advisor who had already been doing it for the last 30 years. I had to find my own thing.”

After completing his PhD, Goheen spent three months at the University of Florida as a postdoctoral assistant to Dr. Todd Palmer, a friend from graduate school he had met in Kenya. Then, in 2007, Goheen accepted an assistant professor position at the University of British Columbia.

“Some of my professional heroes who had done all of these famous ecological studies, both in the Serengeti and in the Yukon, were at UBC,” Goheen said. “I really enjoyed my time at UBC. They had quite a group of incredibly bright animal ecologists and evolutionary biologists there. While I was there, I trained my first graduate students. My first PhD student got his doctorate at UBC and we remain good friends and collaborators. It was kind of through him and my first PhD student at Wyoming that larger mammal research got rolling.

and in the Yukon, were at UBC,” Goheen said. “I really enjoyed my time at UBC. They had quite a group of incredibly bright animal ecologists and evolutionary biologists there. While I was there, I trained my first graduate students. My first PhD student got his doctorate at UBC and we remain good friends and collaborators. It was kind of through him and my first PhD student at Wyoming that larger mammal research got rolling.

“It was initially working on trees that led to this question of herbivory by elephants vs. small mammals. Small mammals eat tree seedlings and elephants eat adult trees, so the question was how comparable are the two sets of effects. Gradually the research transitioned into larger mammals. At that point I had spent enough time out there and gotten to know enough people that it became possible.”

In 2010, Goheen left UBC for an assistant professor position in the Department of Zoology and Physiology at the University of Wyoming, where he would spend the next 14 years, advancing to associate professor in 2016 and full professor in 2020.

“It was a great department with lots of great colleagues and folks doing groundbreaking work on wildlife and ecology and evolutionary biology,” Goheen explained. “Laramie is pretty unusual in that it is a college town in the Intermountain West that is still very much a small, intermountain west town. Wyoming is about as close as you can get to Kenya in the lower 48. There are big open spaces and sometimes there is big conspicuous wildlife in them.”

At Wyoming, Goheen’s research team studied everything from moose to pocket gophers and Pacific martens locally. The group also did a project on various species of bats in the Black Hills of South Dakota. However, the majority of his work has focused on mammals in East Africa, everything from elephants and lions to African wild dogs and lesser-known big mammals like hirola antelope and hartebeest. They also have worked with small charismatic microfauna like gerbils, elephant shrews and pouched mice among other species.

martens locally. The group also did a project on various species of bats in the Black Hills of South Dakota. However, the majority of his work has focused on mammals in East Africa, everything from elephants and lions to African wild dogs and lesser-known big mammals like hirola antelope and hartebeest. They also have worked with small charismatic microfauna like gerbils, elephant shrews and pouched mice among other species.

One standout research project began looking at the interaction between trees, ants and elephants and revealed connections between ecosystem dynamics and predator prey interactions.

“One of the nuts that we’ve been able to crack out there is a project that started through that postdoc I had at Florida,” Goheen said. “There is an acacia tree out there that forms monocultures, meaning you see that tree and only that tree and lots of that tree. When you see that ecosystem, it is quite striking and it is quite different from how most people envision the tropics as hyper diverse with lots of species. In this case, this one species of tree is a myrmecophyte, it defends itself with ants. That tree offers food and shelter to ants in exchange for the protection that the ants provide. It was long thought that those ants were defending trees against insects that wanted to eat the trees. In fact, the ants defend the trees against elephants, and because of that, they are able to form these monocultures. If you are not a myrmecophyte, you get completely thrashed by elephants. That interaction between the ants, trees and elephants give rise to these monocultures.

“Roughly a decade ago, my collaborator and friend Corinna Riginos discovered that there is an invasive ant that kicks out the native bodyguards. Unlike those native symbionts, it doesn’t live on the tree, it lives in the cracks in the soil and forms colonies of hundreds of thousands of individuals that go up and down trees and numerically overwhelm and kill native ants. Then, elephants detect that, start eating the trees and transform the monocultures into something way more open. In those open landscapes, lions have a harder time killing zebra and they switch to eating buffalo. It has been a really interesting story to unravel. Ten or 15 years ago I had a student that started working on lions and then these two parallel lines of research came together with predator-prey interactions with lions and the ant-plant-elephant story. It was rewarding to tie those programs together.”

Beyond the animals and ecosystems he works with and in in East Africa, Goheen also was intrigued by another pattern.

“The first thing everybody notices in Kenya is that there are big mammals everywhere and you don’t have to look too hard for them,” Goheen stated. “That was the initial grab. But the second thing that was actually more of a mystery to me at the time, was that a lot of the folks doing research and conservation of wildlife in Kenya were rarely Kenyans themselves. That made me curious. I wondered if that might contribute to a long-term challenge for wildlife conservation. So, in addition to scratching my itch about wildlife and ecology out there, that became something I was interested in pursuing. Once I became a professor, I tried to train a few more Kenyan graduate students.”

Among the many students that Goheen has trained, Dr. Abdullahi Hussein Ali and Dr. Carolina Ng’weno, his first two graduate students at the University of Wyoming, are two of his success stories. Ali, who studied the range restoration and conservation of hirola antelope in northeastern Kenya, is now the founder and coordinator of Hirola Conservation Programme. Ng’weno who studied predator-prey dynamics and livestock production in Laikipia, Kenya, is now the director of research of Nature Kenya.

“Both of them are exceptional individuals,” Goheen shared. “Ali worked with hirola antelope, a very little-known species in eastern Kenya and western Somalia, which we think is the rarest antelope on Earth. There were only 400 to 500 of them about 12 years ago. Ali is from the one part of the world where the hirola still occur. I was introduced to him through a mutual friend and he said he wanted to do his PhD on the species. By virtue of his insanely high work ethic and ability and his cultural connections with the area, he was able to do a dissertation where probably no one else on Earth could have. What he discovered was that this species of antelope had been on the decline for 30 or 40 years due to tree encroachment in the area. Tree cover increased because elephants were poached out of the area in the 1970s and 80s and this antelope depends on open plains and grasslands. Through his dissertation, Ali was able to work with locals to form a non-government organization that could conserve the species and he has done it by restoring open grassland to benefit the hirola, which has increased their numbers.

“Caroline is a fantastic young scientist and she is the first woman in the country to have a PhD in wildlife to be working in that field. She did her dissertation on lions and their hunting behavior.”

In addition to bringing students from East Africa to study in his lab, Goheen has worked more broadly with Kenyan students and wildlife professionals in general. He works with the National Museums of Kenya to identify aspiring African conservation biologists. They do field work and learn study design, as well as how to trap, handle and identify small mammals as part of long-term experiments in the country.

“At this point, six individuals from NMK have worked as project managers out there and most of them go on to graduate school and have influential careers of their own,” Goheen said. “It is a partnership where we try to get motivated, talented young mammalogists in the field.”

Goheen also has worked with colleagues in the American Society of Mammalogists to establish the African Research Fellowship, which provides funding to African scientists working on the ecology, conservation and evolution of African mammals. As an ASM member since 1996, Goheen and others who worked in Africa followed the lead of some Latin American mammalogists who were building partnerships and strengthening ties in that part of the world.

“The limiting step for a young African student who is interested in mammal ecology is often simply money, so the bang for the buck out there is pretty high,” Goheen explained. “There were enough folks that were in a position to donate some startup funds for this African Research Fellowship program. So, in 2013, half a dozen of us formed this committee with the goal of identifying promising African mammalogists who are in graduate school or want to go to grad school and give them a pretty modest amount of money to do some work.”

Through his own research to his work with fellow scientists in Africa, Goheen has made an impact across the globe. Upon finding out his efforts had earned him Purdue FNR’s 2024 Distinguished Alumni Award, Goheen was grateful yet humbled.

“Two of my grad school friends and colleagues Robin Russell and Todd Atwood were honored with these awards (in 2021), and I never thought of myself in the same category with those two,” Goheen said. “I was very pleasantly surprised. Awards are never the motivation why somebody gets into this profession, but it is really nice to be recognized. I feel very honored.”

In looking back on his career and what got him to this point, Goheen shared advice he would give future wildlife biologists.

“One of the common threads for me is that I’ve been fortunate to have a ton of really good mentors, more than anyone should,” Goheen stated. “Each set of interactions led to the next set of interactions in this really linear way. You have heard the phrase people make their own luck. I think I wasn’t the best student or the best biologist and I wasn’t born with a gift to do it, but I have always tried to understand when there was an opportunity there and I’ve had more than my fair share of opportunities in that regard.

“My first piece of advice is to be careful of advice, because what worked for me may not work for you. There are lots of ways to skin the cat, which is what I really like about science: there are different ways to do it. So, I guess the advice there is to ask as many people as will give you the time of day for advice and then figure out the common denominators. My second piece of advice is to recognize that what you are doing today isn’t what you are going to be doing tomorrow. You may have very specific career goals, but don’t pass up a summer job or grad school opportunity because it appears unrelated to your long-term goal. You have to allow for flexibility and recognize opportunities when they come your way.”

Goheen has found a new opportunity of his own recently, hiring on as an assistant professor in the Department of Natural Resources Ecology and Management at Iowa State University in January 2025.

“They advertised for a global wildlife ecologist and I thought, this is what I do and it’s what I have done for the past many years and it is what I want to be doing for the next many years,” Goheen said. “I thought it was a good move and I am excited to do it.”

No matter the job title or location, it is clear that Goheen will be continuing his wildlife research and conservation work both domestically and in Africa for many years to come.