Dr. Joe Robb Earns Chase S. Osborn Award for Wildlife Conservation

The Chase S. Osborn Award in Wildlife Conservation, which was established in 1952 by former Purdue President Edward C. Elliot, is presented by Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources to an individual who, by writing, research, teaching or other personal accomplishments has made distinctive contributions to wildlife conservation in the state of Indiana. The award has been presented 38 times since its inception in 1953.

Purdue President Edward C. Elliot, is presented by Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources to an individual who, by writing, research, teaching or other personal accomplishments has made distinctive contributions to wildlife conservation in the state of Indiana. The award has been presented 38 times since its inception in 1953.

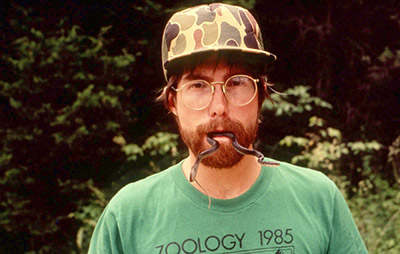

Dr. Joe Robb, who earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Forestry from Purdue in 1982, is the 2024 recipient. Robb has spent the last 26 years serving the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service at the Big Oaks and Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuges. He has mentored more than 160 interns over the years and taught conservation courses at Ohio State University and Hanover College, impacting the next generation of natural resource professionals. His efforts to establish youth deer and turkey hunts at Big Oaks led the way for similar hunts across the state. The certified wildlife biologist was instrumental in discovering, helping conserve and even doubling the population of the state endangered crawfish frog at Big Oaks. He also has authored numerous publications on a variety of species and management techniques including a recent guide to implementing adaptive management in the National Wildlife Refuge System. He helped establish both the non-profit land trust Oak Heritage Conservancy in southeastern Indiana and the non-profit refuge friend group, Big Oaks Conservation Society. Robb also has served the field of natural resources through his work with the Indiana chapter of The Wildlife Society, for which he acted as president in 2006, and through his work as a reviewer for several journals and publications.

“I feel really honored to be awarded the Chase S. Osborn Award for Wildlife Conservation,” Robb said. “Wildlife conservation is by no means an individual effort and this award equally belongs to my mentors, partners and co-workers as we strive and fight for wildlife conservation in Indiana. As I look thru the list of prior award winners, I see several names of those who have taught and mentored me and I feel blessed to be included in such a remarkable list.”

It Began with Monarchs, Caterpillars and Grasshoppers

Robb grew up in Marion, Indiana, as a “very nerdy kid.” He grew monarchs and cecropia caterpillars. He caught grasshoppers in the wood lots and near the railroad tracks close to his home. He had little gardens at home. He was fascinated with a ninth-grade leaf collection project, which required gathering and identifying leaves. The traces of a future career of seeking out and managing wildlife were present early on.

“I always wanted to see some of the birds you see in field guides as a kid,” Robb said. “I saw redheaded woodpeckers when I was young because there were dead elms all over the place because of Dutch elm disease, but I never saw a blue bird. Now in my career, I do lots of bird stuff and I see all of those types of birds that I never saw as a kid.”

In sixth grade, Robb realized at an environmental camp that working in conservation was something that he was interested in. A few years later, after receiving the Lena Wall Raschbacher scholarship to Purdue, he decided to enroll in the forestry program.

“It was kind of an unruly group of kids running around chasing each other with axes, but I really liked that camp,” Robb said. “It taught me some of the basics of conservation, management and environmental ethics. When I got the scholarship at Purdue, I thought about doing pre-medicine and took some classes, but conservation and being outside was just what I really liked. It seemed the students in pre-med didn’t really seem to like medicine, they just wanted the title and the career. In forestry and wildlife, the people really liked that stuff so I got involved with that.

“Purdue was a great experience for me. I got involved with the Wildlife Society late in my tenure; I wish I had started earlier. One of my biggest regrets is that George Parker talked to me about being a field helper for his dendrology class and I was too busy. As an undergrad, you don’t realize what chances you have. I had all of these other classes and things to do that I was more concerned about. I realize looking back that those types of things were important.”

started earlier. One of my biggest regrets is that George Parker talked to me about being a field helper for his dendrology class and I was too busy. As an undergrad, you don’t realize what chances you have. I had all of these other classes and things to do that I was more concerned about. I realize looking back that those types of things were important.”

FNR Summer Camp as well as the many professors and courses in FNR and related majors made an impact on Robb.

“Summer Camp was very informative,” Robb shared. “I enjoyed it. I had a very good experience and spent a lot of time learning nuts and bolts of wildlife management in the field. Dr. (Russ) Mumford was very good. He was one of the old-time naturalists and had a world of experience. I also made a lifelong friend with Al Parker, who also contributed to conservation in Indiana with his work with bald eagles in the state.

“Another person who was pretty good to me was Virgil Brack, the bat ecologist. I was able to do some surveys with him after graduation to get some money so I started to learn consulting, both state and federal. I really enjoyed the taxonomy classes. Sam Postlethwait, who was one of my botany professors, and George Parker, Mickey Weeks and Dr. Claire Merritt were all very good to me. There are so many folks throughout my career that spent time with me and gave me opportunities.”

Robb took advantage of his summers to gain work experience on research crews, including three years as an assistant crew leader for the Summer Wildlife Crew at Salamonie Reservoir for the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Joe and his wife Amber grew up in the same town and went to Purdue on the same scholarship and worked together at Salamonie Reservoir. They reconnected in 1998 and blended their families and continue to support one another in their careers.

“I started to learn bird calls on the Summer Wildlife Crew,” Robb noted. “Those were the kinds of things where the summer experience reinforced what I was learning in class. Those experiences led me to going out to Mount St. Helens and working with Doug Andersen, who went on to work with the U.S. Geological Survey. I also worked as a field tech out at the Purdue Wildlife Area putting in gopher enclosures for Doug after I graduated. He is actually the one who told me that someone at Ohio State was looking for a master’s students. I worked with Jeff Kiefer at the wildlife area and he ended up being the lead for USFWS Partners for Fish and Wildlife in Indiana and really contributed to private land conservation in the state.”

Robb studied under Dr. Ted Bookhout at Ohio State, working on a master’s project looking at natural cavity nesting in wood ducks, funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The two presented about the “Importance of Nesting Cavities and Brood Habitat to Wood Duck Production on Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge” at the Midwest Fish and Wildlife Conference in 1985 and published several papers from that work over the next few years.

Wildlife Refuge” at the Midwest Fish and Wildlife Conference in 1985 and published several papers from that work over the next few years.

After completing his master’s degree in 1986, Robb was hired on as an assistant manager for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service based at Reelfoot National Wildlife Refuge in Tennessee. He spent three years at Reelfoot, including two in which he doubled as a collateral refuge law enforcement officer.

“I wasn’t the world’s best law enforcement officer, but I learned things,” Robb stated. “I learned a little bit of maintenance, I learned how to get along and how to work in a team. In this job, it is a team and all about partnerships and learning how to deal with different people.”

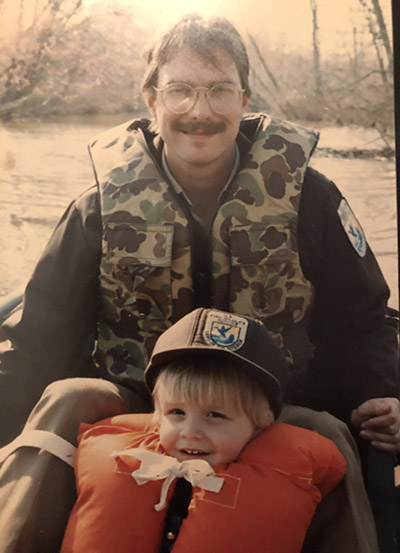

After taking a few years off from school to spend time with his young son, in 1989, Robb returned to Ohio State to work on his PhD, while working as an intermittent refuge operations specialist at Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge. He did his research in the Lake Erie wetlands and lived at Winous Point Shooting Club, completing his dissertation on “Physioecology of Staging American Black Ducks and Mallards in Autumn” in 1997.

State to work on his PhD, while working as an intermittent refuge operations specialist at Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge. He did his research in the Lake Erie wetlands and lived at Winous Point Shooting Club, completing his dissertation on “Physioecology of Staging American Black Ducks and Mallards in Autumn” in 1997.

“I did a lot of duck and wetland work, working mostly with black ducks and mallards up at Lake Erie, looking at how they gained fat levels and how it contributed to their survivorship,” Robb said. “I have some nice memories of my son drawing little things on my data sheets when I would take him radio tracking and pictures of him banding ducks with me. I had great technician help in both my master’s and PhD work and made good friends and memories while we did all that hard work.”

After a short postdoctoral research position and stint as a lecturer in the Ohio State School of Natural Resources and Ohio Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Robb started applying for full-time positions. He applied for jobs at Ohio State, at Ducks Unlimited in Louisiana and with the USFWS at Jefferson Proving Ground, which is now Big Oaks National Wildlife Refuge in Madison, Indiana. He took the latter position, planning to stay for just a couple of years to pay students loans and take care of his family. That was 27 years ago.

“I did my master’s down at Muscatatuck, so I knew it very well,” Robb shared. “Originally it was just going to be a temporary position trying to figure out whether the place would be a good refuge or not. It is a proving ground for the military, where they test munitions. I remember when I was doing my master’s I heard bombing going on in the distance there at the Jefferson Proving Ground.”

When Robb arrived at Muscatatuck, Steve Miller, who is now the acting refuge manager at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, worked with Robb to establish the refuge. Robb was tasked with writing the legislation to see if the land could be transferred to the refuge system. Although there were concerns with the munitions, Robb and Miller figured out an overlay workaround with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, worked with Robb to establish the refuge. Robb was tasked with writing the legislation to see if the land could be transferred to the refuge system. Although there were concerns with the munitions, Robb and Miller figured out an overlay workaround with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“There were issues with some of the federal laws and the Army’s responsibility for the munitions, but everything we found showed there weren’t really contaminants that affected wildlife populations,” Robb noted. “There were munitions, which factor into how we manage the land, but there was all kinds of biodiversity and all kinds of neat wildlife. Even today, we keep finding neat wildlife there, including species that could be soon classified as endangered. Initially we were granted a 25-year permit and we just renegotiated it a couple years ago to a 99-year permit.”

Working at the refuge, first as an operations specialist for four years, then a refuge manager for 10 and as a project leader at Muscatuck and Big Oak National Wildlife Refuge Complex since 2013, Robb has worked to gather facts, information and feedback on management that can be shared. He also has passed his knowledge down to countless interns.

“I expect a lot out of interns and I sometimes push folks into things where they are uncomfortable initially,” Robb said matter-of-factly. “I am not everyone’s cup of tea, but I always encourage them to try different things. I remember doing bird work with one intern, finding and monitoring nests in different kinds of forests where there was an Acadian flycatcher female. The female makes a different call when she is building a nest or around a nest. I said, if you hear that, find the bird’s nest and don’t come back until you find it. She had a look of horror and said ‘what if I don’t find it?’ She found it and we laugh about it now.

“A lot of wildlife is observation and persistence. Learning new skills, trying different things, collecting data, communicating and becoming part of a team are things we try to do with all of our interns. Some people flourish and blossom in front of your eyes. And some may become a dentist or physician or work in environmental law and that is fine too. They should just love what they are doing.”

The Chase S. Osborn Award is presented for distinctive contributions to wildlife conservation in the state of Indiana, of which Robb has many.

“I decided to nominate Dr. Robb for the Osborn Award after spending an afternoon riding around Big Oaks with him in preparation for a field tour we were hosting,” Purdue extension wildlife specialist Jarred Brooke said. “I was humbled by the stories he shared and the remarkable management efforts he showcased during our time together. From crawfish frog restoration and monitoring Henslow’s sparrow populations to implementing prescribed fire on a challenging landscape shaped by its history as a military base, his work stands out. His team’s success in navigating a long-term agreement between the Department of Defense and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to protect Big Oaks for at least the next 99 years is a testament to their dedication. The accomplishments of Dr. Robb and his team are truly a conservation success story for Indiana.”

One of the standout projects that Robb and his team have worked on is the conservation of crawfish frogs. Robb and Daryl Karns, who was a professor at Hanover College, were out with some students one night and thought they heard crawfish frogs off in the distance near the Air National Guard’s Jefferson range. Later, Robb discovered that their ears were not mistaken.

“After that, I would walk out in areas that we had burned and I started seeing frogs go into holes,” Robb recalled. “Eventually Kerry Brinson at Jefferson Range was mowing and saw something strange; we both observed this frog go down a hole and saw that it was in fact a crawfish frog. Then one night, one of my interns found one on the road. We started surveying there and found they were just everywhere that the habitat was good on the property. So, then the question became how did they get here. They could have been here all along and a remnant population increased as the land was cleared and returned to the way the Native Americans had it when they were doing slash burn agriculture along with bison trails that came through the area. Or maybe they could have been transported here by accident through a fisheries stocking. Or they could have spread east with the land clearing. We don’t know.”

It took a while to find a successful pond. Robb and his team would find some ponds where the eggs were laid and they would dry up. They would consistently find big older frogs but no young frogs when they first started. Eventually, the team concluded that the new bomb craters when the Army was testing were acting very much like a bison wallows and crawfish frogs really like an early successional wetlands, ponds without a lot of competition or predation.

They tested methods such as treating and draining ponds and found the frogs preferred drained ponds. Then, Robb and his staff found a wetland with successful metamorphs and began comparing a random selection of ponds to try to replicate the successful pond through wetland restoration and draining and managing ponds. Those efforts were successful and the population began growing, although not without challenges. Success also brought evidence of diseases and parasites, such as Ranavirus and Perkensia infections, two conditions that brought mass die-offs.

“There are a lot of questions,” Robb said. “If we can figure out how various conditions are affecting things, it could change management and restoration work. We are happy to have doubled the population of crawfish frogs at Big Oaks, but there is more work to be done.”

Another aspect of land management Robb has focused on in his time at the refuges is prescribed burns.

“Henslow’s sparrows and Indiana bats were the first things we worked with because both seemed to be influenced by fire,” Robb explained. “We started a fire program here and radio tracked Indiana bats to see where their maternity colonies were in trees and some of those were in in areas that were influenced by fire. We also did work with the forest and grassland birds and that morphed into working with the Henslow’s sparrows. We started finding a lot of nests and that resulted in some publications. Then that morphed into cerulean warbler work that resulted in some interns doing master’s graduate work. The work that the fire management officer Brian Winters did was essential in building that fire program and he was great to work with.”

influenced by fire,” Robb explained. “We started a fire program here and radio tracked Indiana bats to see where their maternity colonies were in trees and some of those were in in areas that were influenced by fire. We also did work with the forest and grassland birds and that morphed into working with the Henslow’s sparrows. We started finding a lot of nests and that resulted in some publications. Then that morphed into cerulean warbler work that resulted in some interns doing master’s graduate work. The work that the fire management officer Brian Winters did was essential in building that fire program and he was great to work with.”

Robb has worked with others within the refuge system – namely Melinda Knutson, Pat Heglund and Heather Tonneson - to assemble a book of best practices for other managers. Forging the Future: A Guide to Implementing Adaptive Management in the National Wildlife Refuge System helps managers avoid trial and error type management by offering suggestions for how to improve data collection and when to do adaptive management vs. a research project, etc.

“We started looking at the success and failures of different management techniques,” Robb noted. “It is hard to do adaptive management because of the time and commitment required to get the data and analyze it every couple of years, so research projects can be a lot quicker. Trying to identify how and when to do that type of work was a group project we worked on for several years.”

Robb also has been instrumental in implementing deer and turkey hunts for youth across the state. With the rules and regulations that apply to wildlife refuges, he was able to work with the Indiana Deer Hunters Association and local conservation officer Andy Crozier to begin an early youth hunt. After a few years of trial runs, resulting in successful hunts at Big Oaks involving up to 150 youth, the practice has been incorporated statewide thanks to proof of concept.

rules and regulations that apply to wildlife refuges, he was able to work with the Indiana Deer Hunters Association and local conservation officer Andy Crozier to begin an early youth hunt. After a few years of trial runs, resulting in successful hunts at Big Oaks involving up to 150 youth, the practice has been incorporated statewide thanks to proof of concept.

Working with a team of interested parties, Robb helped establish the non-profit land trust Oak Heritage Conservancy in southeastern Indiana.

“All of the private interest groups, the non-government organizations and the state all got together and talked about our needs and what was working and not working,” Robb said. “One of them was that there was a hole in the land trusts in this area. We just didn’t have coverage, so we got a group of folks together who were willing to be the board and started getting it designated as a non-profit. Dan Webster, a professor at Hanover, who was on the board at the time, donated some of his land and boom, we had a land trust.”

The Oak Heritage Conservancy is now in the process of potentially merging with others locally to make a better case for funding and to hire permanent staff.

Robb also helped form and establish the non-profit refuge friend group, Big Oaks Conservation Society. The group – “pillars of the community – from retired surgeons to pharmacists and lawyers – that are my liaison to the community” can raise funds, talk to legislators and support the refuge in ways that Robb and his colleagues cannot. They help fund activities like the youth hunts and an outdoor women’s event and support the Christmas bird count among other things.

Community science - from the Christmas bird count to the North American butterfly count to its first bio blitz in 2024 - is important to Robb’s mission of getting the biodiversity of the refuge to be more known and to have the spaces better utilized by locals.

“Our mission is to preserve, conserve and manage wildlife habitat for future generations of Americans,” Robb stated. “We are wildlife first, serving hunting, fishing and wildlife observation. We have a lot of biodiversity and that is why we fought hard for this place. We are America’s best kept secret as far as conservation, people just don’t know about the refuge system. There is so much here and we keep finding more species and need more help to document it all.

“We have all these plant and wetland resources that clean the water and filter out the agricultural silt and chemicals throughout our landscape. That allows us to have mudpuppies and salamander mussels, which may be put on the endangered species list. We have cranberry here. That’s a northern plant, but we have it here because we have all of these little niches and things find there way here and survive. All of these things matter. They are all connected and talking about these larger landscapes is important. The real challenge is getting land trusts and state partners and everyone to work together to try to keep it all going.”

For his part, Robb is invested and, despite the honor of joining the ranks of the Chase Osborn Award honorees, he won’t be stopping anytime soon.

“If you look at some of the people who are on the list of Chase Osborn Award recipients, those are some great, great conservationists and wildlifers that have really contributed a lot in the state,” Robb noted. “It is a real honor to be included with them. I’ve worked hard and I love this and if you are passionate about it, there is always more to do. I’m very curious and very stubborn, so I will keep trying until things work out.”