Patrick Ruhl Selected for Osborn Early Career Award

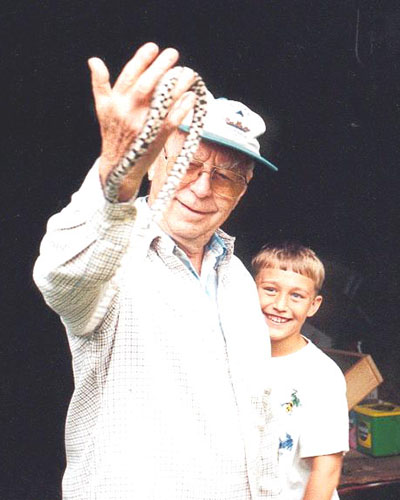

Patrick Ruhl grew up in West Lafayette, Indiana, within a stone's throw of Purdue University. He played tennis on the William Henry Harrison High School team. The son of a biology teacher has early memories of catching bugs, flipping over rocks and logs to find salamanders, going on hikes, and hunting and fishing.

Patrick Ruhl grew up in West Lafayette, Indiana, within a stone's throw of Purdue University. He played tennis on the William Henry Harrison High School team. The son of a biology teacher has early memories of catching bugs, flipping over rocks and logs to find salamanders, going on hikes, and hunting and fishing.

"Spending time in a deer stand just appreciating the sounds and sights, or being on a lake at night and hearing the frogs singing and the owls and appreciating the beauty of the night sky, all of those things funneled me toward a great appreciation for the systems that are required to keep things working the way they need to, how all the pieces work together and how, if things get out of balance, you can lose the frogs singing or the salamanders can disappear from the streams or the woods," Ruhl reminisced. "In a natural progression, I just followed my passion."

That passion led Ruhl to study biology at Harding University in Arkansas, where he was surrounded by a faith-based community and encountered professors who honed the appreciation and value of nature first instilled by his parents, Joe and Gail. Those professors helped transform Ruhl from 'the kid who came to class decked out in camouflage and was only interested in all things deer: deer hunting, deer management, etc.' by helping him realize that a good scientist pursues the relevant important questions no matter what species happens to be the focal point for a particular study.

"I took some key classes in my undergrad at Harding," Ruhl recalled. "I took a great herpetology course with Dr. Mike Plummer and Nathan Mills, both of whom were awesome herpetologists at this small Christian school in Arkansas. I just lucked out. They both really enjoyed their focus species, but the difference was that they were really in it to answer the interesting scientifically relevant questions. Through a lot of prodding and development and through different classes, they got me to realize that there's a difference between being a gee-whiz kid and being a scientist. They took me from just thinking salamanders and birds are cool to diving deeper into what scientifically relevant, ecologically important questions we could address that could have more of a broad impact, while still focusing on organisms I found interesting. They took me out of the 'I want to study deer because I like deer hunting' mode and into a more conservation minded, ecosystem centric world view. They made me want to follow the questions."

Because he spent his summers back home in West Lafayette and his father had connections at Purdue, Ruhl found himself volunteering to assist with various research projects for Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources students during his undergraduate years. Projects ranged from planting chestnut seedlings for Dr. Rob Swihart in multiple plots based on difference in canopy coverage and soil type, to setting up transects and doing small mammal trapping for Pat Zollner's student Val Clarkston for her research on flying squirrel demography at Jasper Pulaski Wildlife Preserve.

Because he spent his summers back home in West Lafayette and his father had connections at Purdue, Ruhl found himself volunteering to assist with various research projects for Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources students during his undergraduate years. Projects ranged from planting chestnut seedlings for Dr. Rob Swihart in multiple plots based on difference in canopy coverage and soil type, to setting up transects and doing small mammal trapping for Pat Zollner's student Val Clarkston for her research on flying squirrel demography at Jasper Pulaski Wildlife Preserve.

"It broadened my horizons a bit, but I was volunteering on projects that wouldn't necessarily get me out of bed in the morning," Ruhl said. "Over time, I learned about different management techniques that go into maintaining different types of habitat. It was cool and interesting and I was learning about all of these different mammal species I didn't know about, but also the greater context of experimental design. Those sorts of concepts kept building upon one another and seeing real life examples of that was beneficial for me. That is not to say that I went into my master's completely understanding how to set up an experiment without any pitfalls, because that was not the case, but they were good experiences."

A two-week intersession ornithology course at Harding opened Ruhl's eyes to the diversity of birds and the problems associated with bird conservation and wildlife conservation in general. He knew at that point that he wanted to get a master's degree and work in conservation, which led him back to Purdue and contacts he had made over the years.

Initially, Ruhl planned to study birds under Dr. Barny Dunning, but research needs set him on a different path. A mark and recapture project with Plethodontidae, a family of lungless salamanders, at the Southeast Purdue Agricultural Center (SEPAC) piqued Ruhl's interest. The study, which was already underway when Ruhl arrived, was part of a biomass harvesting program that was investigating how those types of harvests, which take everything out of a site, could be detrimental for ecosystem services, especially for bioindicators like salamanders.

Initially, Ruhl planned to study birds under Dr. Barny Dunning, but research needs set him on a different path. A mark and recapture project with Plethodontidae, a family of lungless salamanders, at the Southeast Purdue Agricultural Center (SEPAC) piqued Ruhl's interest. The study, which was already underway when Ruhl arrived, was part of a biomass harvesting program that was investigating how those types of harvests, which take everything out of a site, could be detrimental for ecosystem services, especially for bioindicators like salamanders.

"The stand had already been established, the treatments had already been set up, so it was a good master's project," Ruhl said. "I didn't have to do any of the planning, I was just going to pick up a project that had already been started and carry it on to completion, but I ran into a lot of problems with how I would have set the methodology up differently. I ran into a lot of issues, but it was a good learning experience for me to figure out how I would do it differently if I was going to set up a study, which really prepared me well for going into my PhD. I learned that you basically need to know how you are going to analyze your data before you ever step foot into the field."

After completing his thesis, "The Effects of Biomass Harvest on Eastern Red-Backed Salamanders," at SEPAC, there was a mutual feeling between Ruhl and Dunning that they would like to continue to work together.

"I really enjoyed Barny as an advisor and he was an awesome mentor," Ruhl stated emphatically. "We were able to figure out our relationship and use the master's project as a trial run and then get down to business for the key questions we wanted to work on for the PhD. We figured out that we really worked well together and so if there was money available, he wanted to keep me in his lab and the feeling was mutual. I mentioned that I really wanted to study birds with him. The Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment had already been underway for a decade or so, and the system was primed for figuring out things about mature forest bird associations, so it all worked out."

A project right at the heart of forest management implications for breeding birds in the state needed addressed, but most researchers did not want to tackle it because it involved working in six- to eight-year-old clear cuts, which consist mostly of intense vegetation and brambles, and setting up and monitoring mist nets for 60 days each summer.

A project right at the heart of forest management implications for breeding birds in the state needed addressed, but most researchers did not want to tackle it because it involved working in six- to eight-year-old clear cuts, which consist mostly of intense vegetation and brambles, and setting up and monitoring mist nets for 60 days each summer.

"I think what stands out about Patrick's work was his willingness to tackle difficult questions that took a great deal of fieldwork, time and sweat," Dunning said. "He did a three-year field project as part of his PhD where he was banding birds throughout the summer, collecting feathers, blood and fecal samples from dozens of birds. This meant that he was out in the field before sunrise and working in densely vegetated clearcuts filled with brambles and thorny plants. Most people wouldn't tackle the questions that he addressed because it was just too much work. Patrick did it all with great enthusiasm; he just loves working with birds and being in the field. His results were surprising to many of us (for one thing, he found that the most common birds he caught in the clearcuts were species thought to be restricted to older forest) and that meant that he was in demand to give talks on his research all over the state. He became a real spokesperson for the benefits of active forest management to private landowners throughout the region. The published papers from his master's and PhD research are all used by public land managers as guides for how to manage our public lands."

With backing from conservation organizations like Amos Butler Audubon Society and several other small grants from local Indiana Audubon societies and the Indiana Academy of Science, the funding was acquired and Ruhl got to work planning the massive project despite a few concerned glances from researchers questioning his massive undertaking.

"I went to a couple of meetings with researchers on the HEE before I started the project and when we got to the point where they learned that my plan was to set up mist nets in the clear cuts, it was a little daunting to see their reactions," Ruhl remembers. "They would say good luck or have fun with that, or it sounds good on paper, but I need to show you what these sites look like. It is basically just Rubus and Smilax, blackberries and greenbrier, copperheads and rattlesnakes."

Ruhl stuck to his plan of setting up mist nets in each of the six clear cuts on the different research units on the HEE. He would sample each for a 10-day period over the summer. To prepare for the project, the first winter he took a GPS, trimming sheers, loppers, a hacksaw and measuring tape to the sites to measure and create openings for the 12-meter long mist nets, which had to be placed a standardized distance from the forest edge. He cleared and flagged the areas, but the following summer when he came back to start his field season and place the mist nets, the vegetation had already grown back. But Ruhl was undeterred. In fact, as time went on, he kept adding more data points to the study.

Ruhl set up a sampling array around each net, 12 one-meter square plots, which were measured for vegetation density. After banding birds each morning, Ruhl and his cohorts counted the exact number of ripe blackberries in the plots each afternoon. They also did vacuum sampling for invertebrates each day to associate insect availability for the leaf-gleaning species that the team caught. They also did the same with pitfall traps for birds foraging on the ground. Halfway through the study, they also began taking blood samples. Questions about roosting habits of female worm-eating warblers, a species of special conservation concern in Indiana, brought Ruhl to put radio transmitters on some of his mist net catches to track their movements.

Ruhl set up a sampling array around each net, 12 one-meter square plots, which were measured for vegetation density. After banding birds each morning, Ruhl and his cohorts counted the exact number of ripe blackberries in the plots each afternoon. They also did vacuum sampling for invertebrates each day to associate insect availability for the leaf-gleaning species that the team caught. They also did the same with pitfall traps for birds foraging on the ground. Halfway through the study, they also began taking blood samples. Questions about roosting habits of female worm-eating warblers, a species of special conservation concern in Indiana, brought Ruhl to put radio transmitters on some of his mist net catches to track their movements.

"Looking back, it seems a bit sadistic that we would subject ourselves to that level of torment, but by getting really accurate counts each day, we were able to look at different habitat covariates and food variables," Ruhl said. "We learned that the only way you could find out what was there was to get in there and do it. The questions really started to drive the enthusiasm and the research project forward at that point. Initially I went into it with the question of what's happening in the clearcuts, but we ended up catching a bunch of things we did not expect, which brought many more questions and side projects."

The findings of the research bore the benefits of the team's diligence and extra efforts. Mist net catches showed that there were many more family groups, or parents with their fledglings, and mature forest birds occupying the clearcuts than previously thought. Through the blackberry and vegetation surveys, they were able to establish a trend line of ripe fruit availability in the clearcut and directly correlate that with scarlet tanager abundance in the clearcuts. The vacuum sampling provided a look at other food variables that could be correlated to the appearance of various species. Blood samples showed that there was niche partitioning between mature forest species, or that they were each using the clearcut for slightly different resources.

Prevailing knowledge prior to Ruhl's research was that mature forest species such as worm-eating warblers only came to the clearcuts in the post-fledgling period, but Ruhl and his team caught several adult birds a month before the first fledgling was thought to occur.

Prevailing knowledge prior to Ruhl's research was that mature forest species such as worm-eating warblers only came to the clearcuts in the post-fledgling period, but Ruhl and his team caught several adult birds a month before the first fledgling was thought to occur.

"The high association of adult birds with the clearcuts way before phenologically they should have been there was an interesting discovery," Ruhl said. "We know that they are one of the first to recolonize after an early successional opening like that, but we were able to learn some interesting things and apply that knowledge to conserving the species."

A major discovery was how prevalent mature bird species were in the clearcuts especially in the early part of the breeding season when they were expected to be mostly in the mature forest.

"One of the benefits of being a grad student with a major professor who knows a lot more than you do about something is that when you come to them with data, you get to watch their jaw drop to the floor and then you realize that it is significant. To me, saying that we caught 120 worm-eating warblers in the clearcuts this year was just a number. But as I presented the data at various Audubon society events across the state and at the national ornithology meeting, every time I shared that story and saw people's reactions it ignited my fire to try and explain it more or figure out what the data meant."

Radio tracking of female worm-eating warblers, which were assumed to be in the clearcut for the post-fledgling period, brought another major finding. Evidence showed that these birds may in fact have been nesting in the clearcuts as they were caught in June, which was early according to commonly held beliefs about their phenology and compared to any records for the state of Indiana. Ruhl also found that these birds were roosting, or spending the night, in the clearcuts, which offered key information about their life history.

"Tracking the worm-eating warblers, we didn't expect that they would be the most abundant or most commonly encountered bird in the clearcuts, but in three years we caught over 500 individuals," Ruhl recalled. "That first year we caught so many worm-eating warblers and saw an interesting trend in terms of how and when we caught them, that opened the door for so many questions of what they were doing in  there, how it related to our understanding of their breeding phenology and habitat use and post fledgling ecology and led to tangentially related projects that involved nest searching, characterizing their nest habitat and even basic bird biology. There are still many questions to be answered, even within that system. What I learned is that it doesn't have to be groundbreaking, national news type science for it to be important. You can find out what worm-eating warblers are doing in southern Indiana and it can be really important for informing a lot of conservation efforts."

there, how it related to our understanding of their breeding phenology and habitat use and post fledgling ecology and led to tangentially related projects that involved nest searching, characterizing their nest habitat and even basic bird biology. There are still many questions to be answered, even within that system. What I learned is that it doesn't have to be groundbreaking, national news type science for it to be important. You can find out what worm-eating warblers are doing in southern Indiana and it can be really important for informing a lot of conservation efforts."

Another finding of the project was that chestnut-sided warblers were detected in the clearcuts, hundreds of miles south of their known breeding range, and that they were breeding on the HEE as evidenced by behavioral observations and females spotted with fledglings later in the season.

After completing his PhD on "Postfledgling Habitat Associations of Mature Forest Birds with Early Successional Habitat in South-Central Indiana" in 2018, Ruhl was hired as an assistant professor of biostatistics, environmental science, ecology, herpetology and ornithology at his alma mater, Harding University. In addition to his teaching, Ruhl is Director of the Gilliam Biological Research Station, a 700-acre property where he incorporates the forestry knowledge he gained at Purdue and implements best management practices on the pine plantations and powerline right of ways as well as a low wetland habitat, which is ideal for salamanders.

Although Harding is not a research institution, Ruhl has found ways to engage his students in research projects to give them hands-on field experience. As a certified bird bander, he does weekly bird banding at the property with his undergraduate students. Currently, his students are tackling questions about wintering sparrows, of which five species live at Gilliam. One student is preparing to do radio telemetry next winter. Another is going to do point count surveys for breeding birds in the spring. Two others are collecting blood samples from sparrows to look at diet and prey items based on stable isotope data. A radio transmitter project on song sparrows may also be on the horizon.

"I learned from Barny what a good professor looks like, one that engages undergrads in hands-on activities," Ruhl said. "It is cool to be able to teach in the way that I saw Barny teaching and interacting at summer camp and at banding outings at the Purdue Wildlife Area. I think you can tell when the professor is fired up about the questions and it makes students want to be involved. I'm learning how to be the mentor/professor that I saw in Barny and he has really made an impact on how I teach my conservation biology and ornithology courses and my teaching style in general. It is cool to hear what my students are doing now and how they are applying some of the things they've learned as they go on to graduate school or into other areas."

"I learned from Barny what a good professor looks like, one that engages undergrads in hands-on activities," Ruhl said. "It is cool to be able to teach in the way that I saw Barny teaching and interacting at summer camp and at banding outings at the Purdue Wildlife Area. I think you can tell when the professor is fired up about the questions and it makes students want to be involved. I'm learning how to be the mentor/professor that I saw in Barny and he has really made an impact on how I teach my conservation biology and ornithology courses and my teaching style in general. It is cool to hear what my students are doing now and how they are applying some of the things they've learned as they go on to graduate school or into other areas."

Ruhl is just four years removed from completing his PhD, but there is no question that his research has made an impact on Indiana conservation, especially that of worm-eating warblers, making him a deserving early career recipient of the Chase S. Osborn Award for Wildlife Conservation.

"I was really surprised and honored when I received the call from Barny," Ruhl said. "Being a professor at a small liberal arts school, you can lose sight of some of the impact you have had as a researcher. There's a heavy focus on teaching. I try hard to incorporate research and I'm lucky enough to teach a lot of classes that are more research based, but it is encouraging to know that my research efforts have been recognized and all the work that went into them is making a real difference. The real award is knowing that the stuff that we figured out is being used to better inform wildlife management practices."

"I was really surprised and honored when I received the call from Barny," Ruhl said. "Being a professor at a small liberal arts school, you can lose sight of some of the impact you have had as a researcher. There's a heavy focus on teaching. I try hard to incorporate research and I'm lucky enough to teach a lot of classes that are more research based, but it is encouraging to know that my research efforts have been recognized and all the work that went into them is making a real difference. The real award is knowing that the stuff that we figured out is being used to better inform wildlife management practices."

One of Ruhl's major collaborators over the years has been 2021 Chase Osborn recipient Ken Kellner, with whom he has completed four publications. Ruhl acts as the "bird guy" with the knowledge of the system and how it all fits together, while Kellner is the "stats guy with the math brain." Ruhl notes that without his fellow graduate students, including Kellner; research assistants in the field; the many individuals who have been part of the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment, and his graduate committee made up of a diverse group of professors, those results would not have been possible.

"Coming into the grad program I had this idea that I had to be an expert, but what I ended up coming away with is that nobody can be a jack of all trades," Ruhl said. "Science is so collaborative and what I learned at Purdue is that good projects have experts from this field and that field, and a data analysis part and isotope part, etc., and everybody comes to work together on this thing that is bigger than any one of those individuals by themselves."