Plant scientists maintain critical research to save data and irreplaceable plants

The College of Agriculture accounted for more than a third of Purdue researchers who asked for access and support to continue critical research when facilities closed this spring.

Adapting mid-experiment

With about 15 wiliwili trees in the Lilly Greenhouses, and only 150 left in the wild after an insect pest decimated its population, Purdue oversees an important concentration of this deciduous tree native to Hawaii. Scott McAdam, assistant professor of botany and plant pathology, has been growing the trees for three years.

His research broadly focuses on drought responses in land plants. When the campus shut down in March due to the coronavirus outbreak, McAdam and his graduate student, Cade Kane, were studying the mechanisms that trigger the wiliwili to shed its leaves to survive the dry season. Such experiments last three to four months.

“It’s almost impossible to stop these experiments once you get going,” McAdam says. Kane had been labeling every leaf for five months. By noting when each leaf was initiated and tracking when it fell — Would the oldest leaves fall first? — the research team hoped to identify a physiological trigger.

“Coming into March, we had four months of labeled leaves,” McAdam says. “To create a drought takes about a month. When the university had to shut down, the idea that we could just work on the computer now was impossible.”

But that wasn’t McAdam’s only concern. He works with a collection of living plants, many of which are rare or irreplaceable, or that would require international travel to source again. Spring semester, he had three graduate students and a lab technician taking turns to water and monitor them daily — enormous tree ferns from Hawaii; relatives of maize from Central America; Gondwanan flora from South America, New Zealand and Australia; and rare plants from across North America.

“These are plants not very common in cultivation but extremely useful in research,” he explains. “They couldn’t be left behind.”

The College of Agriculture tried to accommodate McAdam and many of his colleagues so they could keep their projects going. “While much research at Purdue slowed, the college was able to keep 160 labs open during the pandemic due to their essential research and the need to get fields planted this spring,” says Bernie Engel, associate dean of research and graduate education. As of May 11, the College of Agriculture accounted for 152 of 406 requests university wide to continue critical research.

McAdam says such support and cooperation among his colleagues prevented any loss of his beloved plants, and that his research is “slowly coming back from survival mode.”

Photo provided by Scott McAdam

Photo provided by Scott McAdam  Photo provided by Scott McAdam

Photo provided by Scott McAdam New professor, new MS student

When Diane Wang arrived at Purdue in January as a new assistant professor of agronomy, she was especially excited to begin her research in Purdue’s Controlled Environmental Phenotyping Facility (CEPF). “This is the best growth chamber in the world to grow crops,” she says. “These types of phenotyping facilities that give you fine control over environmental conditions are rare.”

The CEPF is an important resource for Wang, who develops and tests computer simulation models of how different crop varieties grow in response to environmental distress — ultimately, to improve plant breeders’ predictions under novel climatic scenarios. By the time the university closed campus facilities in March, she had three experiments growing in the CEPF on brassica, papaya and rice. The studies on the genetics and physiology of rice would form the basis of her new graduate student’s master’s degree.

When the CEPF shut down, Wang terminated the first two experiments. The brassica studies are in collaboration with Miami University of Ohio, so Wang felt she had some backup. Papaya seeds can be difficult to germinate, so she took some of the plants home. “They sheltered in place with me, so we lost no time on those,” she says.

Her first concern actually wasn’t the growing plants at all; she was most worried about her master’s student. “Things are so new for me, but she had just started graduate school and I couldn’t even imagine how she was feeling about all the uncertainty,” Wang says.

Master’s degree students are normally on tight timelines, and Wang’s student must complete these studies in preparation for next year’s field season in Stuttgart, Arkansas. “I didn’t want to throw her research off course,” Wang says. “That was the primary concern for me — my responsibility as a mentor to help her get her research done in a timely manner.”

Wang and her student met virtually every week through the shutdown to discuss theory, project management, relevant literature, and general topics. And although the CEPF was closed, their rice continued to grow there. “The nice thing about the CEPF is that it’s almost 100 percent automated, and it’s easy to socially distance there,” Wang says. “[Facility manager] Chris Hoagland has been fantastic and can do a lot remotely from his computer at home.”

After a few weeks, Wang and her student were allowed back in to the CEPF, as different research teams carefully work around each other’s schedules. As a new faculty member, the gradual ramping-up time allowed Wang to refine her research priorities and procedures. “Having that space to think and prioritize has made me realize how important organization and planning are,” she says.

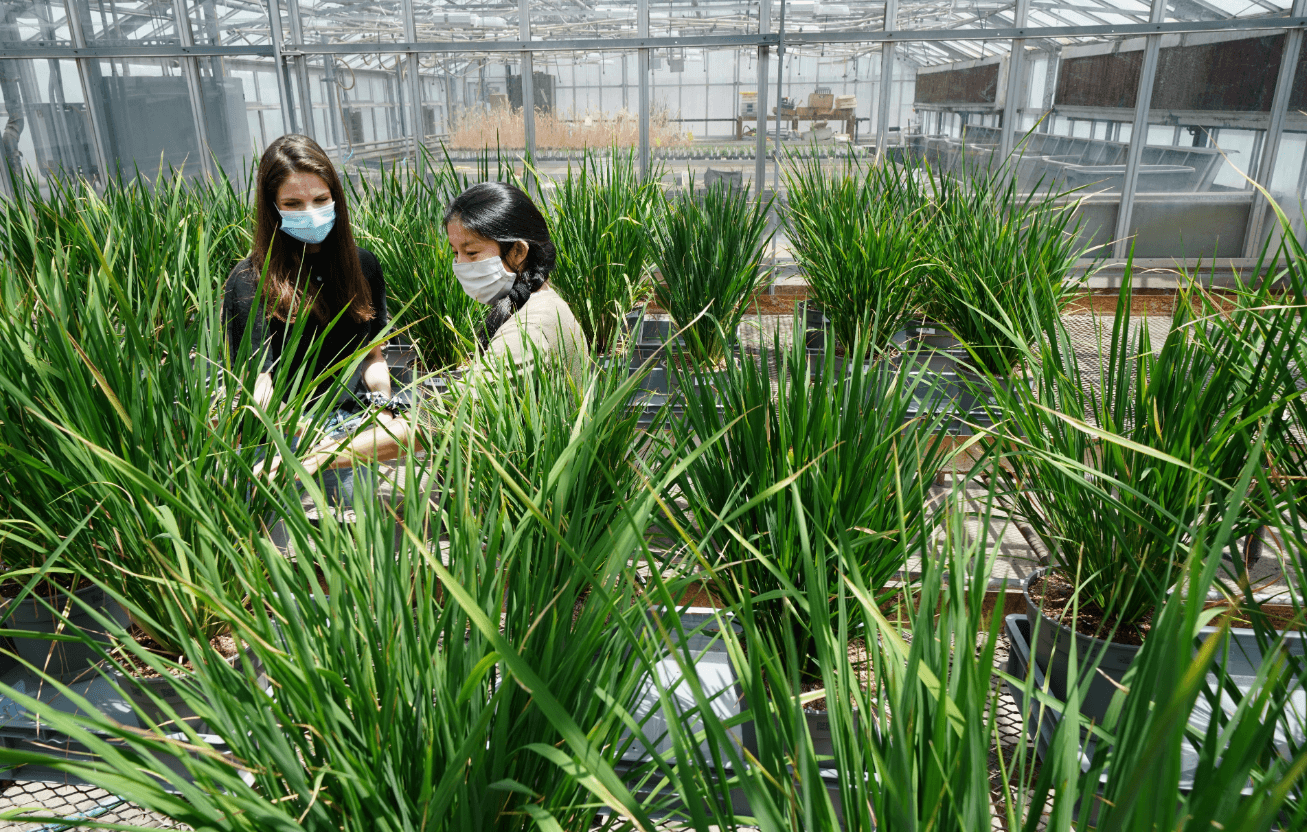

Diane Wang and her master’s student, Rachel Imel

Diane Wang and her master’s student, Rachel Imel Saving time and data

John Couture, assistant professor of both entomology and forestry and natural resources, had two entries on the critical research list — one a short-term project mostly in the CEPF; and the other, a longitudinal study with a small forest plantation at Martell Forest. In both projects Couture uses hyperspectral data to tell him how the plants are faring, just at different scale and scope.

So whether he’s studying novel technological approaches to advance breeding in maize for traits that confer yield stability under drought stress, or is in year three of five tracking disease spread among the trees, he didn’t relish the prospect of losing data over a months-long delay.

Initially Couture’s biggest concerns were his team’s health and converting his Plant-Insect Chemical Ecology class, which included a lot of hands-on activities, to an online course during spring break. He then turned his attention back to his research.

“We took a brief pause in the CEPF to figure out how we deal with this,” he says. “On the second project, we had some time to make preparations.”

Couture sent his graduate students home with samples and instructions to write. “My grad student was asking, ‘When can I get back to my plants in the greenhouse?' I said, ‘just wait — we’ll keep them alive.’ The students have data, and writing is as good an exercise as doing any type of lab work. It all needs to get written up at some point.” Meanwhile Couture and his lab manager and technician took turns watering plants with a mutual goal of sheltering in place and keeping things alive.

It worked. “Once more information came out, we were able to schedule people in the lab, one at a time for a long time,” Couture says. Operating procedures evolved with the availability of PPE and more information. “We feel more comfortable having a few people in the lab, but it’s not full by any means. We’re still being cautious.”

Couture says that as a researcher, “what happens in nature is what I’m interested in, so long-term projects are important.” But based on his experiences this spring, he’ll continue to balance his large, multiyear field projects with smaller projects that can be completed under certain conditions within a certain time frame. He also intends to work with his graduate students to envision their dissertations earlier, building in time to adjust schedules if needed.

Early on Couture realized he didn’t know if any of his students or staff might be at risk due to health issues. “You try to encourage best practices, but you don’t know everything that is going on in people’s lives,” he says. “On an interpersonal level, this has made me more aware of the importance of discussing general life with students and put that in the forefront for me.”