FNR Alumni Keep History Afloat

The improvement of forest trees is the work of centuries. So much more the reason for beginning now.

– George Perkins Marsh.

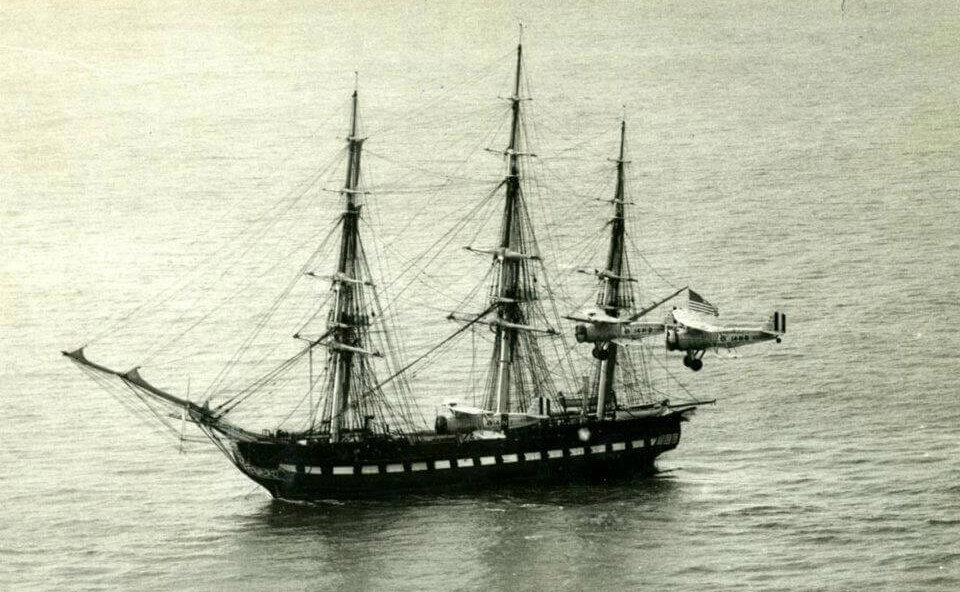

USS Constitution being greeted by Curtiss OC Observation Aircraft. Photographed during her 1931-34 cruise. (Courtesy of Commander Louis J. Gulliver, USN, (Retired), July 1940. Gulliver was in command of Constitution during her 1933-34 cruise. NHHC Photograph Collection, NH 55934.)

USS Constitution being greeted by Curtiss OC Observation Aircraft. Photographed during her 1931-34 cruise. (Courtesy of Commander Louis J. Gulliver, USN, (Retired), July 1940. Gulliver was in command of Constitution during her 1933-34 cruise. NHHC Photograph Collection, NH 55934.) From 1935 to 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Farm Securities Administration purchased more than 30,000 acres of land in southern Indiana under a program seeking to find land under cultivation that was susceptible to erosion, purchase the land and return it to its proper forest coverage.

In 1941, another 35,000 acres were purchased to provide ordnance storage for Navy weaponry, a place where munitions could be stored out of range of potential bombing raids launched from an enemy aircraft carrier.

Together, those land masses became Naval Ammunitions Depot Burns City, established for production, testing and storage or ordnance under the first supplemental Defense Appropriation Act. The base and town were later renamed Crane after Commodore William Montgomery Crane, Chief Officer of the Bureau of Ordnance.

Located 35 miles southwest of Bloomington, Indiana, in Martin, Green and Lawrence counties, Naval Support Activity (NSA)-Crane is now the third largest naval installation in the world by geographic area (108 square miles).

While the Crane base now specializes in developing advanced electronic systems, a handful of workers, many of them Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources alumni, are still working to fulfill the initial goal for the land, sustainable forests.

The work began in 1950s when the first Navy forester was hired. The Department of Defense formalized the work through the creation of a Forestry and Natural Resources program with the passage of the Sikes Act and the first large scale soil and water conservation project on the base, a series of flood control structures and ponds called The Boggs Creek Watershed, was dedicated in 1961. In the late 1960s, Crane foresters began creating forest management plans and conducting timber harvests.

Sustainable management of the now more than 50,000 acres of forest bore fruit in the early 1990s as the base saw its timber output surge from production of an average of 315,000 board feet per year to 2.3 million board feet in 1992, which made Crane the most profitable installation in the Navy by the end of the decade. The base now produces 3 million board feet of timber each year. Every tree is still selected by one of the three foresters on site as part of a 30-year harvest rotation to ensure that the forest maintains its beauty and productivity.

The Crane forests contain mostly white oak, black oak and hickory, which are well suited for the poor soils on the base. Black walnut, black cherry and tulip poplar also dot the forest in limited numbers.

Wood and the Navy

The United States Navy actually owes its start to wood. Six wooden frigates, capable of battling against the Barbary pirates of North Africa to protect the newly minted nation’s merchant ships, while also defending against possible invasion, were commissioned by Congress and President George Washington in 1794.

The U.S.S. Constitution and its cohorts were built out of live oak from southern coastal states and white oak from the Boston area due to the strength, water proof and rot resistant nature of the wood. Of the original six frigates, only the U.S.S. Constitution still floats. It is the oldest warship still afloat in the world. The ship earned its nickname Old Ironsides during the War of 1812, as British sailors observed cannon balls bouncing off the hull of the ship during battle and exclaimed that her sides must have been made of iron.

Throughout the years, the U.S.S. Constitution has required several renovations to keep it afloat. Now, just 12 percent of the wood remaining is original, but the Navy works to keep restorations historical, using the same kind of wood that was utilized when the ship was built and launched in 1797.

Forester Lynn Andrews with the Navy’s District Command in Philadelphia identified the Crane base as an optimal source for timber, and, in November 1973, the base was designated as sole provider of hull planks and non-laminate material.

Crane Answers the Call

Terry Hobson first went to work at Crane in May of 1974 after his freshman year at Purdue as part of a new co-operative learning program in the Purdue FNR department. By the time he graduated in 1978 and was a permanent employee on base, the U.S.S. Constitution had undergone its bicentennial renovation and Constitution Grove had been dedicated.

“They made a big hoopla about it in 1976 and wrote a lot of articles about the Navy base in the heart of white oak country,” said Hobson, who retired in 2010 after 37 years on base. “We never really heard much more about it for a while, then six or seven years before the 1992 dry docking, they contacted us and asked if we were still sourcing trees for them. Being out in the woods all of the time, inspecting the stands and marking a lot of timber, we knew where the better white oak were. In fact, I maintained a listing of the really superior trees and with the development of our GIS system I went back out to GPS the locations.”

The 1990s renovation, which took place in conjunction with the U.S.S. Constitution’s 200th birthday, allowed the ship to sail under its own power for the first time in over 100 years in July of 1997.

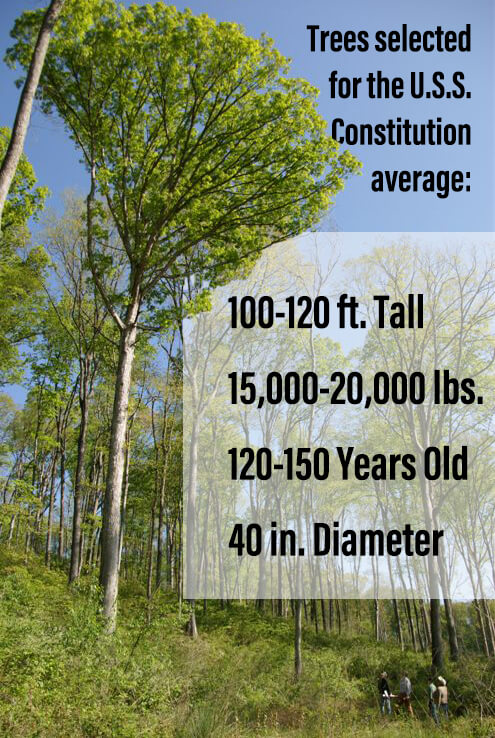

From 1991 to 1994, Crane foresters selected and sent 78 trees to an airplane hanger in Boston, where the logs were milled by a specially designed saw built by Wood-Mizer of Indianapolis.

Timber cutters Marty O’Neal and John Maners and timber buyer Jeff Page (FNR 2001) of Tri-State Timber alongside Trent Osmon (FNR 1999), Rhett Steele (FNR 2001) and Brady Miller (FNR 2001, 2003) of the Crane base stand together during the 2014 cutting.

Timber cutters Marty O’Neal and John Maners and timber buyer Jeff Page (FNR 2001) of Tri-State Timber alongside Trent Osmon (FNR 1999), Rhett Steele (FNR 2001) and Brady Miller (FNR 2001, 2003) of the Crane base stand together during the 2014 cutting. Trent Osmon began working at Crane in June of 1997 under Hobson as part of the co-op program, which was helped the student gain experience and provided Crane with knowledgeable part-time help to complete its forestry work.

“There was an article in National Geographic when I started at Crane and that’s kind of what got me hooked,” Osmon, who is now the Environmental Manager on base. “Terry showed me all of the photos he took when he had driven out to Boston during the restoration and I thought it was the coolest thing in the world. I remember thinking at that point, man, the next time they restore it, in 20 years or so, I want to be a part of it.”

Osmon and his crew, including fellow FNR alums Rhett Steele (2001) and Brady Miller (2001, 2003), were ready in 2012 when the call came in from the Naval Historic Heritage and Command personnel to begin preparations for the 2015 U.S.S. Constitution renovation. Dwight DeMilt and Bob Murphy came from Boston and worked with the Crane foresters to choose the trees that they thought were best suited for the project.

Timber harvest occurs in the late winter/early spring due to the weather as well as the preservation of the Indiana bat, which makes its habitat and summertime flying range in the Crane forests. A competitive bidding process led to Tri-State Timber based in Spencer, Indiana, being selected to harvest the trees. Industrial forester Jeff Page, a 2001 FNR alumnus, organized the harvest and transport of the logs for Tri-State Timber.

“Once we found out we got the job there was a lot of excitement,” Page said. “It’s just something neat to be a part of it, but it also humbles you and kind of puts you in your place. You have a lot of mixed feelings when you see trees of this caliber and are impacting something that is so rare that was around well before your lifetime, both the special trees and the battleship. These are extremely valuable trees. You have to have respect for the resource. It took a long time to grow those trees, and it’s impressive that they made it to that point and are flawless like that. It showcases our state and what we grow here and the benefit of forest management. They have been planning and managing for this at Crane for decades.”

Osmon, Page and Steele each got to cut on or saw down one of the Constitution trees, but Tri-State relied on its two best hand fellers, Marty O’Neal and John Maners, both from Spencer, Indiana, to do the rest of the work. Thirty-five trees were cut and put into storage on base with the plan of sending them to Boston that fall. Due to delays at Charlestown Navy Yard, where the ship is drydocked, Osmon did not escort the first shipment of logs to Boston until July 2015. In total, only 20 logs made the trip to Boston for use on the U.S.S. Constitution, which was in better condition than originally anticipated.

“We grow some of the highest quality white oak in the country,” Steele said. “What we’re doing in the woods on a daily basis is trying to regenerate white oak for future generations, not just for the U.S.S. Constitution.”