Throwing shade: A.I. project a breakthrough in urban forestry

Beyond offering cooling shade, research shows trees can influence microclimates and help reduce the toll of heat waves on the electrical grid and human health. However, the specifics of how trees influence urban areas and the magic number needed for significant heat benefits remains unknown.

A new artificial intelligence-based project aims to advance this research by converting satellite data into accurate tree inventories in urban areas.

“We don’t know much about the trees in our cities and neighborhoods,” said Daniel Aliaga, the professor of computer science at Purdue University who leads the project. “We need to first know how many trees an area has and where they are, before we can understand their impact and plan improvements for the future.”

Physically counting trees is difficult and time consuming, so forestry is looking to remote sensing to quickly gather needed data. Satellite imaging offers the ability to look at almost any area, but one doesn’t have the resolution to identify individual trees, Aliaga said. To cut through the noise and speed tree recognition, his team’s technology follows the philosophy to “simplify and infer.”

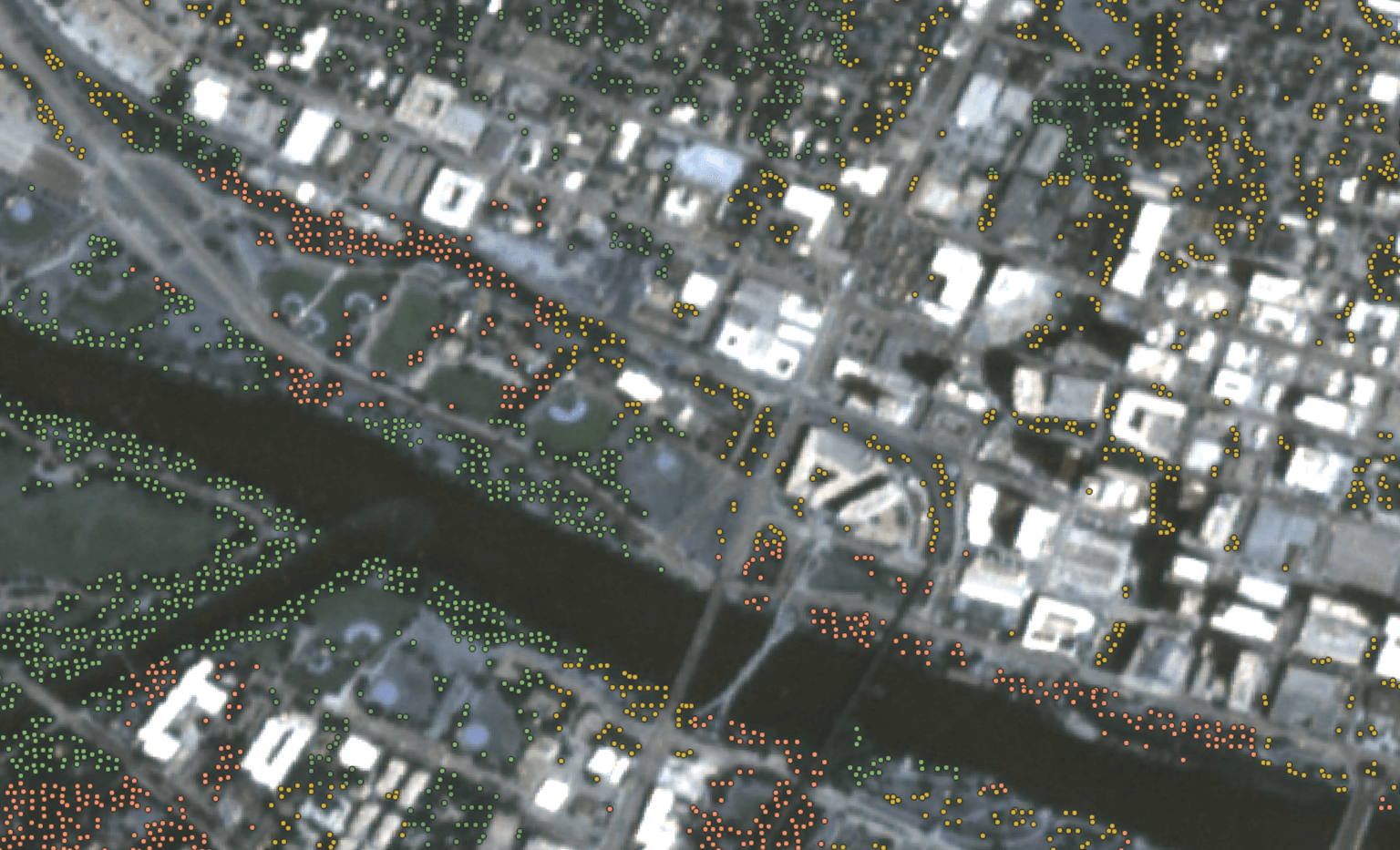

Illustration of a satellite image (3mpp), where trees, not visible from the satellite input image, were located. Trees are categorized by color zones as follows: green circles are parks; yellow circles are roadsides; orange circles are residential areas; and green circles are industrial trees.

Illustration of a satellite image (3mpp), where trees, not visible from the satellite input image, were located. Trees are categorized by color zones as follows: green circles are parks; yellow circles are roadsides; orange circles are residential areas; and green circles are industrial trees. “The real word is too complicated, so we transfer the problem to a simpler artificial world and infer the answer,” said Aliaga, who is part of Purdue’s Next Moves digital forestry initiative. “We look at something more like flickering dots than photorealistic images. Within this simpler construct of the data we use machine-based deep learning to identify patterns that correlate to trees.”

He and Purdue researchers Adnan Firoze, a graduate student in computer science, and Bedrich Benes, professor of computer science, performed experiments over four cities: Chicago, Austin, Indianapolis, and Lagos. A paper in the journal The Visual Computer details the work and show the technology has an accuracy of greater than 90 percent.

Aliaga is a pioneer in the field of inverse procedural modeling, which is the scientific term for the process. Since 2007 he has refined the procedure and applied it to the geometry of cities, traffic and other urban spaces. Forestry was a natural next step in his work, he said.

“We train the deep learning technology with both real-world data and synthetic data that we create,” Aliaga said. “We also take advantage of urban management rules that provide clues like ‘this seems like a backyard’ or ‘this seems like a road’ for the deep learning to follow.”

Another key to the solution of this visualization problem is using data that covers a full year and all seasons, Aliaga said.

“I call the project ‘Trees Over Time’ because that is the heart of it – following trees through the seasons is how we achieve accuracy and efficiency in the tree identification,” he said. “This adds the richness of leaf loss patterns that the technology recognizes as tree-related.”

Aliaga currently works with faculty in Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources including Songlin Fei, the Dean’s Remote Sensing Chair and leader of Purdue’s digital forestry initiative; and Brady Hardimen, associate professor of forestry and natural resources and environmental ecology engineering.

“Our goal is for this technology to one day help urban planners and policymakers craft better spaces for people and the environment,” he said.