From herbaria to fern gametophytes to tree ecology

The COVID-19 pandemic greatly affected all aspects of life, but few realize how much it affected the world of plants. For many people, houseplants became a new hobby, well suited to the long hours inside. Some people realized they have a passion for plants that went beyond looking for distractions. This happened to Sidney Bunch, who started out her academic career studying music education and performance on the cello at Butler University until a prickly succulent—Mr. Cactus to be precise—came into her life.

“I woke up one day,” Bunch recalled fondly, “and out of nowhere, I was like I need to get a cactus. I need to get one. And my mom was like, ‘What are you going to do with a cactus? You don’t need a cactus.’ She finally caved and got me one. And it was my first ever plant. I just kept staring at it. It was just so fascinating.”

From caring for Mr. Cactus and growing other plants during quarantine, Bunch realized how interesting and complex plants were. Butler no longer has a botany program, but she found outlets for her curiosity in working in their botanical garden, herbarium, and in reading botany textbooks on her own time. She made the switch to Purdue University to study plants in the Botany & Plant Pathology department a year ago, and now she’s finding her place as a junior transfer student in the plant science major.

Sidney Bunch poses with the plant that got her started in studying botany, Mr. Cactus, in the library of the Purdue University Herbaria in Lily Hall

Sidney Bunch poses with the plant that got her started in studying botany, Mr. Cactus, in the library of the Purdue University Herbaria in Lily Hall This summer, Bunch is scratching her plant itch by working in the Lily greenhouses and the Purdue University Herbaria, which houses samples of fungi, vascular plants, lichens, and more in the The Arthur Fungarium and The Kriebel Herbarium. Bunch is scanning samples from both collections’ African specimens, barcoding them, and then adding them to a digital database called Specify. This work is funded by a National Science Foundation grant, under which many universities are compiling their African specimens into digital databases so that environmental scientists can access the information.

Working with plants has changed the way Bunch sees the world, so much so that she’s writing an article about plant awareness disparity for the Indianapolis Native Plant Society. “Not as many people pay attention to plants as they should. And, on a large scale, it’s extremely harmful because people aren’t taking in how diverse places that they don’t consider diverse actually are, like Indiana: super diverse! Nobody wants to go build a Walmart in the middle of the Amazon rainforest because they know it’s diverse, and they can see it. But they make environmentally poor decisions when they don’t realize something is diverse.”

Bunch has found mentors from Herbarium Coordinators both at Butler with Marcia Moore and at Purdue with Rabern Simmons. She enjoys getting treated as an equal by them, and their trust in her allows her to work independently. Even though it took her a while to find the right field, Bunch already knows what she wants to do. “Either work at a greenhouse conservatory, like Garfield Park up in Chicago, in the desert or fern room specifically if I had to choose one. I like public horticulture. Another amazing job would be working as a herbarium coordinator.”

Sidney Bunch organizes a sample over a light box to be scanned into the digital database

Sidney Bunch organizes a sample over a light box to be scanned into the digital database Like Bunch, Baylee Riester also came to realize that plants were in her future after exploring other options. She’d wanted to be a vet for the longest time, but then she switched from Penn High School to Mishawaka High School and joined their gardening club. She met her mentor and boss Jake Crawford from the Mishawaka Landscape Department while fundraising to build a greenhouse for the school. That experience pushed her to the plant sciences.

“He definitely inspired me because he’s very passionate about plants and wanting to learn more,” Riester said. “After working for him for so long, and now that I’m here learning about plants, he’s like ‘You know way more than I do. You’re going to have to teach me all the things you’ve learned.’”

Riester, now a senior majoring in plant science and minoring in horticulture, has found her calling in building communities around plants. She designed and planted an orchard of apples, peaches, plums, pears, and cherries for her Mishawaka community in a local park, and she manages it even while still at Purdue. She hopes to use it as a teaching resource as it grows and develops. Riester knows now that her calling is extension and outreach.

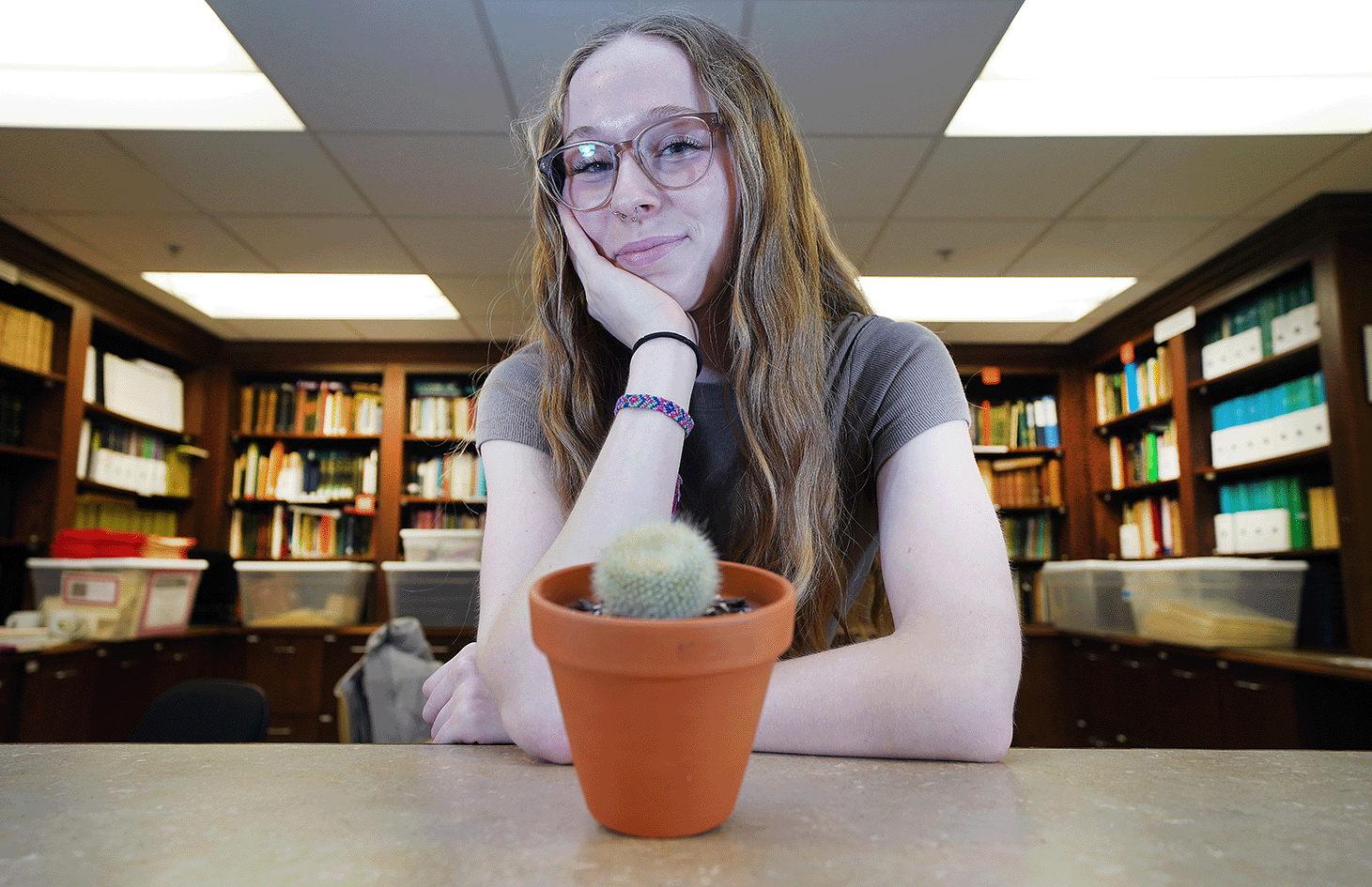

Riester has spent her time in a couple of different labs in the botany department, and she is currently in Yun Zhou’s lab studying the development of Ceratopteris gametophytes, or the young growth stage of a particular type of fern. She spends most of her time making media, plating spores, and—her favorite part—looking at the young ferns under the microscope and taking almost fantastical images of them. Baylee Riester focuses a plate of fern gametophytes under the microscope in her lab

Baylee Riester focuses a plate of fern gametophytes under the microscope in her lab Riester described the daily ins-and-outs of her job in Zhou’s lab, saying “I have to find fern spores that are starting to germinate, and then I treat them with different hormones or peptides. Later, I come back and take images of the gametophytes. In a way, I’m mimicking changes in the environment and seeing how it affects their growth. We can use the information that I got this summer to ask more questions, or see if there’s ways to improve meristem growth in crops and increase their yield.”

While this microscope work and basic science might seem far from the work that Riester would one day do in an extension office, she is reassured that every bit she learns is going to help her and the communities she serves. “I want to use my knowledge to help other people.”

Botany student Levi Berry is also hoping to take everything he learns from the lab to help communities. He is a passionate junior plant science major who worked previously in a molecular lab like Riester’s but is spending this summer interning with Morgan Furze, where he is excited to study trees.

“The reason I wanted to work in this lab is because it was focused on trees and woody perennials and how they interact with their environment,” Berry explained. “The lab’s focused on a lot of non structural carbohydrates, which are carbohydrates that are stored and used for energy. It's a tree ecology lab, and that's what I'm really interested in.”

Levi Berry peers through some young pine trees in the Horticulture greenhouses

Levi Berry peers through some young pine trees in the Horticulture greenhouses The Furze lab is new to campus, and Berry is still deciding what research project he wants to take on there. There are lots of possibilities for him: from researching how lichen that grows on trees can be an indicator of environmental health, to studying how relative biodiversity affects individual plant health with the trees recently planted on small plots in Greater Lafayette. He likes thinking about the bigger picture of how plants interact with each other and their environment.

Berry wants to go to graduate school, and he wants to foster community through urban agriculture. He said, “I would love to further efforts towards food autonomy, increase the biodiversity of urban areas and get more plants into cities.”

Not only is Furze giving Berry the space to explore his different botanical and sustainability interests, but she is also making space for his creativity. Berry is an artist who loves sketching pieces that reflect the beauty and power of nature. With Furze’s permission, he is designing a mural or art wall to brighten up the empty space of the new lab.

Levi Berry sketches out on a bench in the Jules Janick Garden

Levi Berry sketches out on a bench in the Jules Janick Garden