Tomatoes in spaceflight: A giant leap for human (and plant) kind

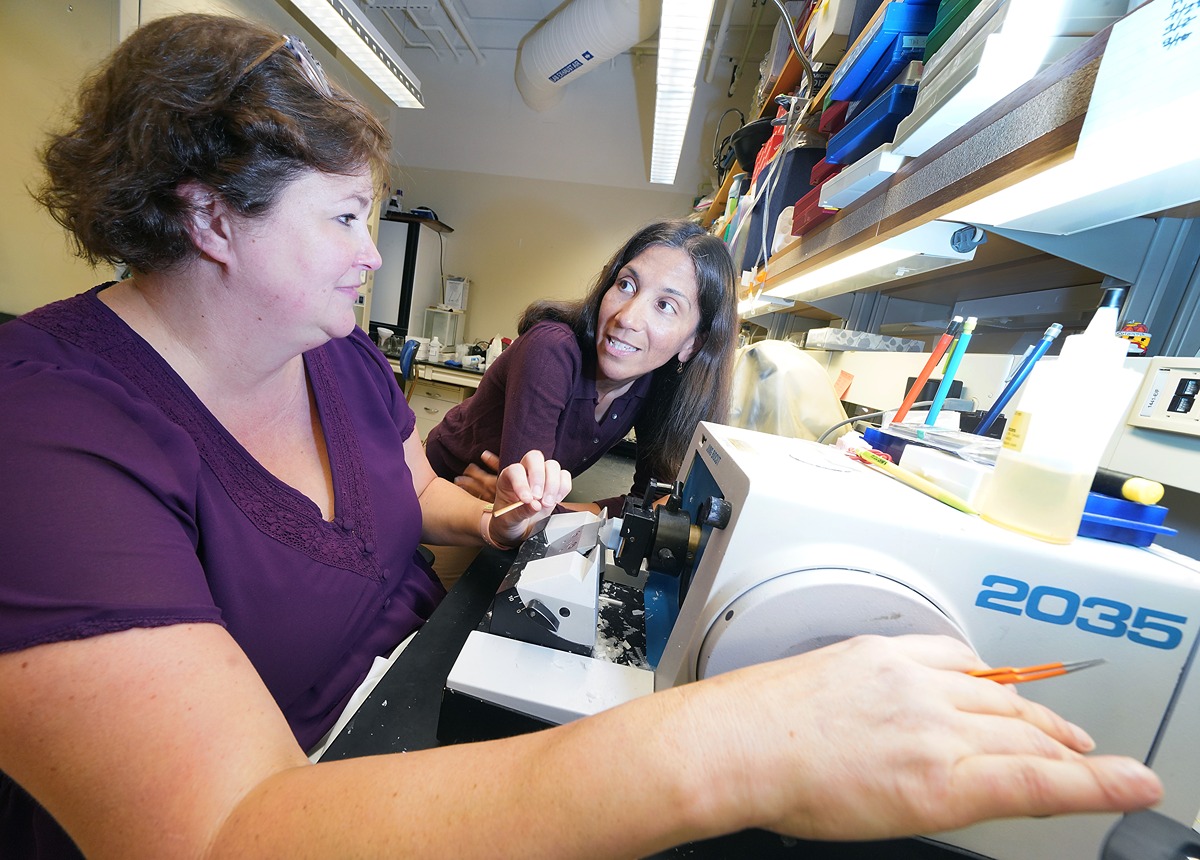

Space calls out to us to explore and possibly discover a second home. But how will humans sustain themselves on years-long flights or in living on another planet? Denise Caldwell, a PhD candidate working in the Iyer-Pascuzzi lab at Purdue, is using her botany powers to lay the foundational knowledge needed to feed ourselves while in space.

NASA wants to send people to the moon and Mars, but they can't do that without growing plants in spaceflight. We’re developing protocols for plant growth on board the International Space Station (ISS) that can be used and adapted by different spaceflight missions for different crops.”

- Anjali Iyer-Pascuzzi, Professor in Botany & Plant Pathology

Plants are already being grown on the ISS. From flowers to spicy peppers, NASA has been testing how different plants grow in spaceflight. There is less gravity aboard a spaceship or satellite—a phenomenon called microgravity—so water and air move differently, and that could affect how food is grown. One of the biggest challenges researchers are facing are pathogens: bacteria, fungi and viruses that can infect the plant and kill them or decrease the yield of food from harvest. Some of these pathogens, like Fusarium oxysporum, have already made their way on to the ISS.

Fusarium oxysporum is a fungus that comes into contact with a plant through its roots in the soil. From there, it causes an infection that makes the whole plant wilt, which means major crop losses. Here on Earth, fungicides help fight Fusarium oxysporum and other pathogens like it, but pesticide application is dangerous for the people aboard in a closed environment like the ISS.

Fusarium oxysporum is a fungus that comes into contact with a plant through its roots in the soil. From there, it causes an infection that makes the whole plant wilt, which means major crop losses. Here on Earth, fungicides help fight Fusarium oxysporum and other pathogens like it, but pesticide application is dangerous for the people aboard in a closed environment like the ISS.

Caldwell is researching how the fungi’s growth and infectious potential would be affected by the microgravity in space. “What we're asking is: can the pathogen colonize tomato plants in space like it does on Earth? If we lessen gravity, can we somehow confuse the pathogen enough that it can't colonize the plant? What happens if the fungus can't sense gravity? Is it going to destroy the whole plant, or will it just destroy root tissue and not go up to the stem?”

To answer these questions, Caldwell and Principal Investigator and professor in botany and plant pathology, Anjali Iyer-Pascuzzi, are working with Erin Sparks, an associate professor in plant and soil sciences at the University of Delaware. They’ve used a clinostat, a device that rotates the plants in a circle similar to how a Ferris wheel spins at a carnival. This motion confuses the tomatoes growing on it so that they can no longer tell up from down. Plants use gravity to tell which directions to grow their roots and shoots, and taking this away from tomatoes has affected their growth patterns, even without any pathogens involved.

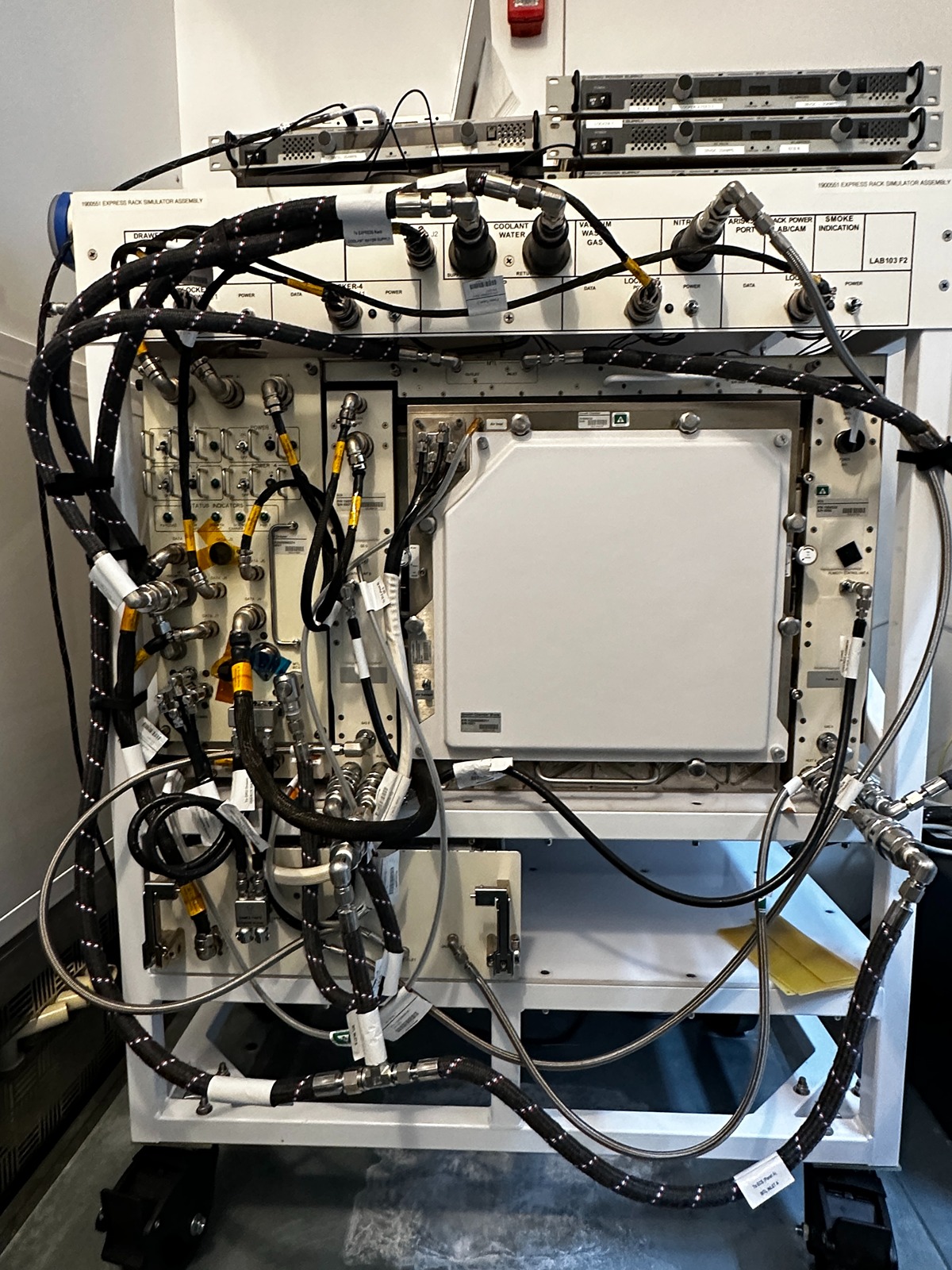

Caldwell has spent the past couple of years preparing tomatoes for spaceflight. They’ll be grown in an Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) aboard the ISS, which is essentially a mini greenhouse with a very controlled environment. Caldwell designed an experiment using a “science carrier” that will form the base of the APH. She had to specialize every aspect of growing the tomatoes so that it would work in space, from exchanging soil for a rocky substrate that can be fully sterilized to adding wicks that help force the water flow to where it is needed around the tomatoes.

Caldwell and Iyer-Pascuzzi will monitor the tomatoes through a camera and give directions to the astronauts on the ISS and Kennedy Space Center to change conditions in the APH as needed. Caldwell will be relying heavily on lessons she learned while completing her horticultural undergraduate degree at Purdue.

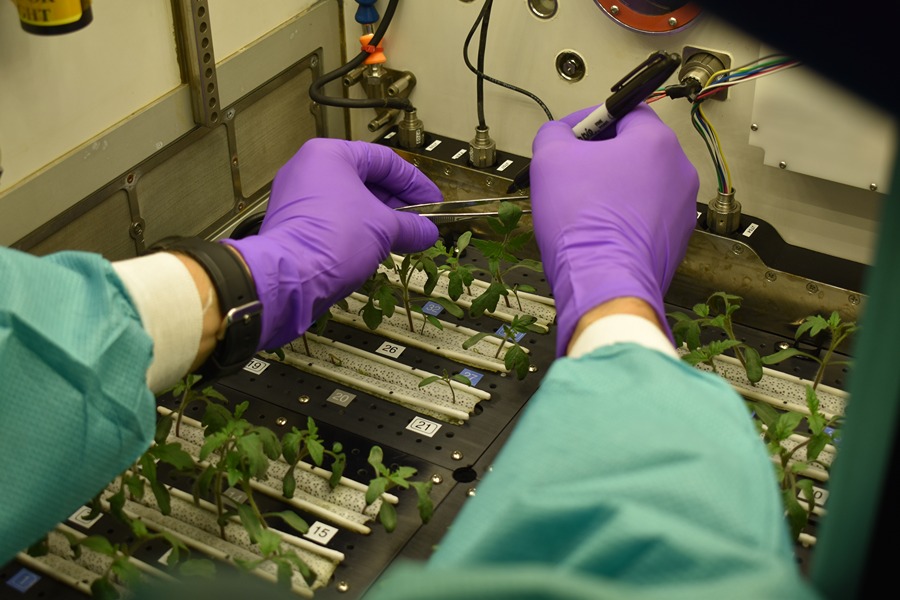

Once the tomatoes are 14 days old, the astronauts will swab some of their leaves with salicylic acid, an ingredient used in facial cleansing products. Salicylic acid acts as a plant hormone that induces the plants’ defense response as if a pathogen were there. This allows Caldwell and her colleagues to see how the plants’ reaction to pathogens changes in microgravity without sending pathogens up to space, which would be a danger to other experiments. Astronauts will then flash freeze the leaves and send them back down to Earth for Caldwell and Iyer-Pascuzzi to study plant-defense gene expression in those samples.

These tomatoes were grown by scientists in an APH at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to predict and give a comparison to how they will grow on the ISS. Photo provided by the Kennedy Space Center.

These tomatoes were grown by scientists in an APH at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to predict and give a comparison to how they will grow on the ISS. Photo provided by the Kennedy Space Center. If all goes well, the culmination of Caldwell and Iyer-Pascuzzi’s work with NASA will take flight on SpaceX CRS 29 aboard the Falcon 9 and reach the ISS in early November. It could be a year or longer until the plant samples come back down to Earth, but Caldwell is excited to see where this science leads.

The Iyer-Pascuzzi lab’s work in space is funded by a grant with NASA: The Effect of Spaceflight and Simulated Microgravity on Plants’ Defense Responses. This means that Caldwell and Iyer-Pascuzzi have coordinated with scientists from Kennedy Space Center, astronauts on the ISS, NASA engineers, and representatives from U.S. Senate sub-committees.

The Iyer-Pascuzzi lab’s work in space is funded by a grant with NASA: The Effect of Spaceflight and Simulated Microgravity on Plants’ Defense Responses. This means that Caldwell and Iyer-Pascuzzi have coordinated with scientists from Kennedy Space Center, astronauts on the ISS, NASA engineers, and representatives from U.S. Senate sub-committees.

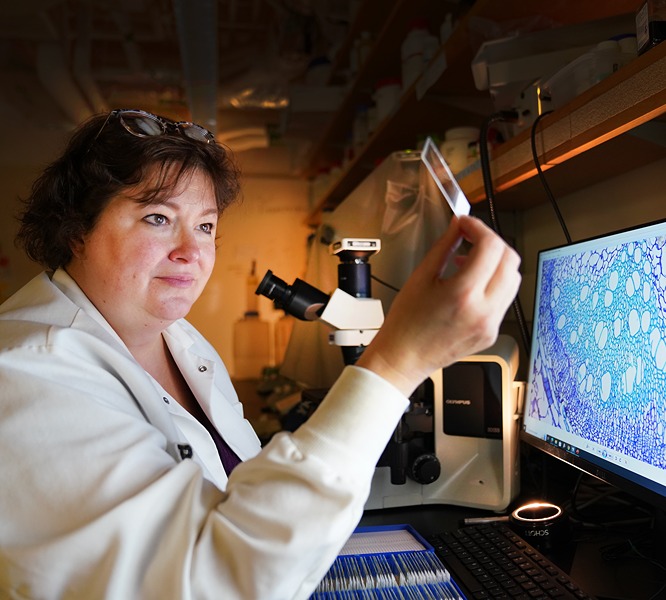

“Denise has done a fantastic job leading this project,” Iyer-Passcuzzi said. “Her combination of horticultural and microscopy skills has made this project work really well.”

Caldwell said she sometimes feels a bit like Matt Damon in the movie The Martian. “NASA told me that we had presented really amazing research, and Anjali and I are going to be the bedrock of this foundation of defense responses in plants for space exploration. After that, we finally realized how instrumental the science we're doing here really is.”

To join Caldwell and Iyer-Passcuzzi and watch the tomatoes take off, be sure to reserve a spot for the virtual viewing of NASA's SpaceX 29th Commercial Resupply Mission Launch.