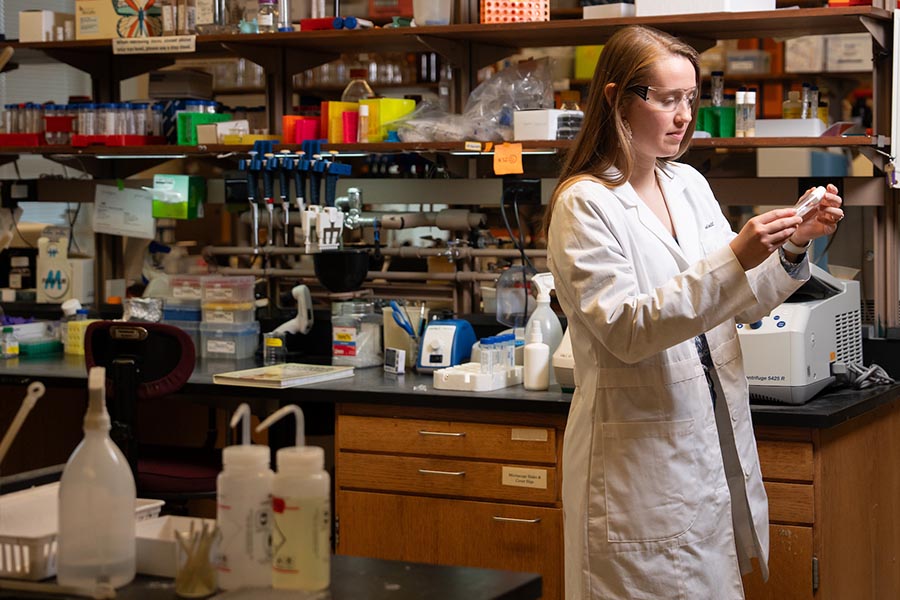

Kendall Cottingham - Graduate Ag Research Spotlight

We’re working at the basic molecular level, but if we can identify a problem in our fruit flies and correct it, this is the basic first step for how drugs get made.

- Kendall Cottingham, Biochemistry

The student

Growing up in Bloomington, Kendall Cottingham was certain that she liked science and was a people person. She figured she’d be a doctor, preferably the kind that doesn’t deal with much blood (she’s a bit squeamish). But while studying at West Liberty University, a small public university in West Virginia’s northern panhandle, an experience opened her eyes to other possibilities.

“I had a roommate who worked in a research lab, and she said, ‘Why don’t you just come to a lab meeting with me, and my boss will give you a project.’ So, I did, and he did.”

Later, that professor took Cottingham and other lab members to an experimental biology conference in Florida. “That’s where I saw research on display for the first time, and I was in awe,” she recalls. “That’s when I shifted my focus from ‘should I be a doctor?’ to ‘I want to pursue research and teaching.’”

Cottingham is now a fifth-year PhD candidate in the Department of Biochemistry.

Purdue was a clear choice, she says. She wanted to be back in the Midwest, closer to family, and she was attracted to the department’s rotation program, where students get to try out different research labs.

When she rotated through Hana Hall’s lab, she knew she’d found her place.

“I was her first grad student,” Cottingham says. “Because of that, I got a lot of one-on-one mentoring and personalized research experience. Her passion for her science was really exciting to me.”

The research

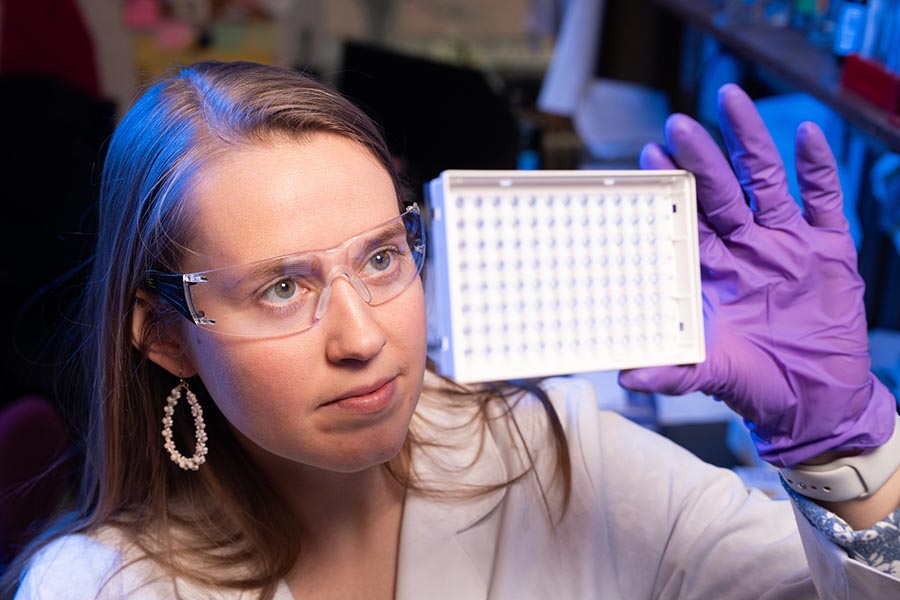

Hall’s lab investigates molecular mechanisms behind age-related neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Cottingham works with fruit flies — which at the cellular level are remarkably similar to humans — to understand how specific RNA modifications might affect neurological function.

“We’re trying to identify where these problems are coming from in neurogenerative diseases and create solutions that could go to human use one day,” she says. “We’re working at the basic molecular level, but if we can identify a problem in our fruit flies and correct it, this is the basic first step for how drugs get made.”

Opportunities

Cottingham’s first conference as a graduate student was in France.

“It was a very niche conference. Only people who study RNA were there,” she says. “So I got to learn a lot of cool stuff from the top dogs of this very specific field we’re in.”

Other conferences have provided opportunities to network more broadly with graduate students and postdocs doing parallel work. “It’s a chance to understand what life is like for other people in my shoes,” she says.

On campus, Cottingham is in her third year as president of the Biochemistry Graduate Student Organization, attends monthly social events with her department and plays pickleball with her lab partners.

“We have a good community. I never feel like I’m just an isolated student working on a project all alone.”

Cottingham and her husband like hosting game nights — Camel Up and Ticket to Ride are house favorites — walking their two puggles and volunteering at their church, where Cottingham mentors a group of sixth and seventh grade girls.

“They ask me how my fruit flies are doing,” she says. “They think it’s a little bit gross!”

Future plans

Cottingham, who expects to graduate next December, hopes to combine her two loves, research and teaching. She was inspired to pursue science by her high school chemistry teacher, who had students play bingo to learn the periodic table. She’d love to work at a small university like her alma mater, West Liberty, where she was able to have regular personal interaction with faculty.

“My favorite thing is teaching someone why I’m excited about what I’m excited about,” she says. “That’s how I got to be where I am.”