Researchers Investigate Effects of 2021 Cicada Emergence

When the 17-year cicada emergence event occurred in 2021, researchers wondered how this sudden influx, or pulse, of easily accessible food would affect mammal activity from dietary responses to roaming habits. Alexis Proudman (BS Wildlife 2024) and her colleagues set up trail cameras and acoustic recorders to find out.

or pulse, of easily accessible food would affect mammal activity from dietary responses to roaming habits. Alexis Proudman (BS Wildlife 2024) and her colleagues set up trail cameras and acoustic recorders to find out.

Proudman, along with Dr. Landon Jones, Morgan Watkins and Dr. Elizabeth Flaherty, recently published the findings of their study in an article titled “Activity responses of a mammal community to a 17-year cicada emergence event” in the Journal of Mammalogy.

“When we started this project, my colleagues and I wanted to determine how the rare mass-emergence of periodical cicadas would affect mammal activity,” Proudman explained. “Our study was unique in that our survey methods were not biased towards predators of cicadas, meaning that we were able to examine non-dietary responses to the emergence as well. We predicted that mammalian carnivores, omnivores, and insectivores would either increase their activity to maximize foraging time or decrease their activity since food would be more easily accessible. We also predicted that mammalian herbivore activity would remain the same since cicadas are not a food resource for these species.”

Research began in the summer of 2021 as a part of Proudman’s internship in FNR’s Diversity in Faces, Spaces and Places Natural Resources Science Research and Extension Experiences for Undergraduates (REEU) program funded by the USDA. The program introduced undergraduate students to research opportunities and extension work, setting up pairs of students with a mentor to create a fully-fledged research project.

Spaces and Places Natural Resources Science Research and Extension Experiences for Undergraduates (REEU) program funded by the USDA. The program introduced undergraduate students to research opportunities and extension work, setting up pairs of students with a mentor to create a fully-fledged research project.

“Throughout this project, I learned that starting a research project doesn’t mean you have to be an expert right away,” Proudman shared. “I failed many times, learned from my mistakes, and finally succeeded in the end. The most important things I learned from this research were to 1) never give up no matter how discouraged you may feel, 2) be brave enough to step out of your comfort zone, and 3) take every chance you can to present your research in front of others. Those three things have given me greater confidence in myself and my capabilities. I found my love for research through this project and I am now a master’s student at the University of Connecticut where I am doing research on bat foraging ecology. After I graduate, I hope to work as a research scientist or mammal biologist.”

Methods

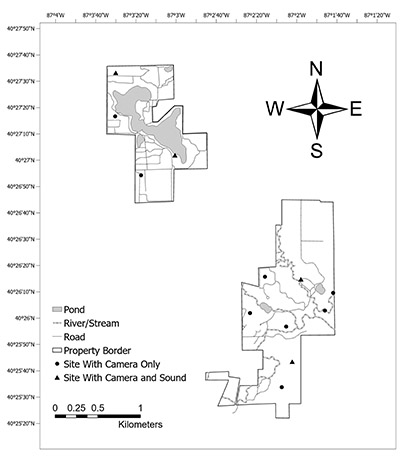

Researchers tested whether the activity levels of eight mammal species in northwestern Indiana shifted in response to spatial and temporal variation in cicada densities by deploying trail cameras and acoustic recorders in Martell Forest and the Purdue Wildlife Area from May 18 to June 20, 2021.

Cameras and sensors were placed in 12 sampling locations (eight at Martell and four at PWA) covering more than 300 hectares. Camera locations were chosen to target areas of likely cicada emergence, or areas where mature forests of hickory, walnut, elm and oak trees existed during the most recent 17-year cicada brood emergence. Browning Strike Force Sub Micro Series Extreme (Model BTC-5HDX) trail cameras were placed 200 meters from one another within each study site to maximize coverage and minimize capturing the same individual animals on multiple cameras. Cameras were pointed toward areas of likely mammal activity such as facing trails or fallen logs. Images were captured 24 hours a day with a fast sensitivity (0.4 seconds), a burst of three photos when motion was detected and a zero-second delay between trigger events.

activity such as facing trails or fallen logs. Images were captured 24 hours a day with a fast sensitivity (0.4 seconds), a burst of three photos when motion was detected and a zero-second delay between trigger events.

To detect the activity of bats and arboreal mammals, such as southern flying squirrels, researchers placed four acoustic recorders at camera locations of past or suspected bat or flying squirrel activity. The Song Meter Mini Bat Ultrasonic Recorders with acoustic microphones attached (0 to 12 kHz or 10 to 120 kHz) were placed at two tree locations each in Martell Forest and PWA. Recorders were set to record for five minutes at the start of every hour beginning at 6 p.m. on May 18 through 6 p.m. on June 19. Acoustic data was analyzed and synced with data from cicada surveys.

Researchers also conducted manual cicada counts every three days. They counted both live cicadas and exuviae, or the molted outer skin of the insect, found in a five-meter radius surrounding the camera traps and also in the three trees nearest to the camera.

Findings

After the five-week study, researchers analyzed camera images and classified terrestrial mammals by species or genus in the event a species could not be distinguished. They also identified bat vocalizations and the vocalization from southern flying squirrels captured by the ultrasonic recorders.

"We identified 10 species of terrestrial mammals from a total of 611 camera images. Six mammal species accounted for the majority of images: Raccoons (Procyon lotor, 224 images, 36.7%); White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus, 119 images, 19.5%); Fox Squirrels (Sciurus niger, 116 images, 19%); Eastern Gray Squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis, 57 images, 9.3%); Peromyscus spp. (44 images, 7.2%); and Eastern Chipmunks (Tamias striatus, 24 images, 3.9%). The other 4.4% of mammal images were represented by Coyotes (Canis latrans, 5 images); Eastern Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus floridanus, 3 images); Groundhogs (Marmota monax, 4 images); and Virginia Opossums (Didelphis virginiana, 4 images).

Coyotes (Canis latrans, 5 images); Eastern Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus floridanus, 3 images); Groundhogs (Marmota monax, 4 images); and Virginia Opossums (Didelphis virginiana, 4 images).

"We identified the following numbers of bat vocalizations by species within recordings: Hoary Bat (7,754 vocalizations, 79%); Big Brown Bat (1,823 vocalizations, 19%); Silver-haired Bat (71 vocalizations, <1%); Little Brown Myotis (54 vocalizations, <1%); Indiana Myotis (52 vocalizations, <1%); Eastern Red Bat (13 vocalizations, <1%); Evening Bat (3 vocalizations, <1%). Additionally, we detected 52 ultrasonic trill vocalizations from Southern Flying Squirrels in 20 acoustic recordings over a period of 2 days in 1 location.

"Across the 12 sampling locations, we counted a total of 2,613 adult cicadas and 6,392 cicada exuviae during 11 cicada surveys. Cicada densities (as exuviae) varied substantially by site across surveys, ranging from 0 to 4.32 exuviae/m2, with a mean of 0.15 exuviae/m2. Between days 15 and 18 (fifth and sixth surveys), cicada density spiked from a mean of 0.01 to 0.22 exuviae/m2 and peaked at a mean of 0.57 exuviae/m2 during the seventh survey. Cicada densities remained high for almost a week before declining to 0.07 exuviae/m2 during survey 10."

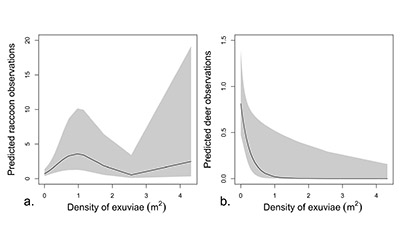

Proudman explained that as predicted, findings showed that raccoons increased their activity as the abundance of cicadas increased, likely a result of the species spending more time foraging on the easily attainable and nutritious cicadas. But, she noted that increased activity was not the only response to the cicada emergence.

“We were surprised to find that white-tailed deer activity decreased dramatically during the emergence, which did not support our predictions for herbaceous species and is not likely explained by foraging patterns,” Proudman said. “Possibly, deer were avoiding areas where cicada chorusing would make it hard for them to hear predators.”

The publication further explains:

"To avoid predation, deer often exhibit vigilant behavior, using visual and auditory cues to detect possible predators (Lingle and Wilson 2001; Lark and Slade 2008; Lashley et al. 2014; Gulsby et al. 2018). The choruses of Brood X species dominate the soundscape of an area (Simmons et al. 1971; Williams and Smith 1991)—consequently, deer vigilance might have been less effective when cicadas were most abundant. Foraging also reduces vigilance in deer (Lark and Slade 2008). Additionally, the cicada emergence in our study occurred during White-tailed Deer birthing. When females are with fawns, they tend to increase vigilance (Lashley et al. 2014). Thus, deer in our study may have: (1) decreased their activity due to increased sound; or (2) moved temporarily to areas with fewer cicadas."

After this study, researchers now have more insight into how mammal communities respond to resource pulses, including the effects that resources pulses may have on non-predatory species. But more work is still to be done.

“There are so many insect-animal relationships that have yet to be discovered, and this research demonstrates that. In the future, I hope research will investigate more insect-animal relationships beyond just predator-prey,” Proudman said. “Future research should use direct tracking methods to understand positive and negative habitat use and fine-scale movements across a gradient of cicada densities. Additionally, exploring potential shifts in diel activity patterns of mammalian species during cicada emergence could give further insight into how these communities respond to resource pulses.”