Pollination: A classic tale of romance, love, and death

Plants are more romantic than you may think. In fact, the story of pollination may as well have been written by Shakespeare himself.

Pollination, an important step in seed plant reproduction, parallels the story of Romeo and Juliet. Specifically, the process of pollen tube reception is much like the classic tale of romance, love, and death.

Sharon Kessler, assistant professor in botany and plant pathology at Purdue, has devoted her lab to studying this phenomenon. Kessler’s lab focuses on the cell communication that occurs between male and female plant tissues during pollination. In other words, Kessler studies how plant cells “talk” and signal to one other.

“It’s like a love story – there’s attraction, dating, and then it culminates in death for both cells,” said Kessler. “It’s really interesting to me. People don’t usually think about the hidden communication that occurs during pollination.”

The search for a soulmate

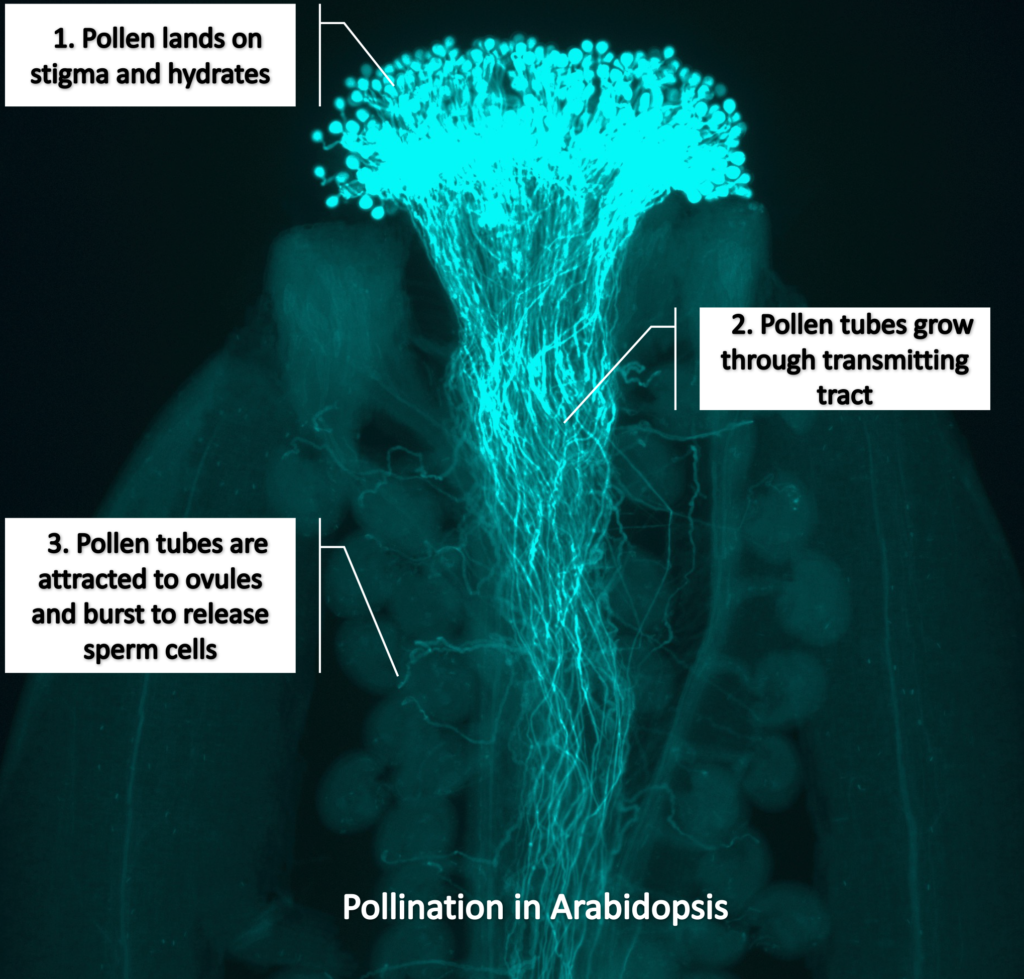

When a flowering plant reproduces, the male tissue of the plant (called the stamen) makes pollen, which contains sperm cells. When the pollen lands on the female part of the flower called the pistil, it grows a pollen tube, which is responsible for carrying the sperm to the ovules. The pollen tube’s search for the egg is much like a person’s search for a soulmate.

The dating phase

Special cells within the ovule, called synergids, emit attractant molecules that tell the pollen tube where to go. You can think of this signaling process as the romantic attraction that happens between two people. The pollen tube “dates” the synergid cells to find just the right place to quite literally spend the rest of its life.

True love

Once the pollen tube finds its “soulmate” synergid, another signaling process occurs, which tells the pollen tube when to burst and release the sperm cells so that fertilization can occur. In plant reproduction, there are two sperm cells and one egg cell. One sperm cell goes to the egg to make the embryo, while the other will fertilize the central cell, which becomes the endosperm of the seed. Endosperm is generally the part of the plant that we eat – like a corn kernel.

Death

Unfortunately, this is the tragic end of our pollination love story. As soon as the pollen tube bursts, it dies. Not only that, but the receptive synergid cell also dies. And although it’s a sad ending, this entire story is very important to agriculture and plant growth in general.

“All flowering plants do it this way,” said Kessler. “It’s one of the evolutionary advantages that allowed plants to grow in a lot of different places.”

The first plants, like mosses and ferns, always had to grow near water. Otherwise, they couldn’t reproduce because the only way that sperm could travel was by swimming.

No one truly understands how pollen tubes evolved, but at some point, the eggs got enclosed within ovules and the sperm got enclosed within pollen. With this tough, protective coating on the sperm, it could fly around in the air or be carried by pollinators. But then the sperm needed a way to get to the egg. That’s why the pollen tube evolved.

“But then you’ve got to have a mechanism that allows the female to tell the pollen tube when it’s arrived in the right place,” said Kessler. “That’s exactly our research – how does the female communicate with the male to tell it it’s at the place at the right time.”

Geneticists, cell biologists, and molecular biologists all work together in Kessler’s lab to explore these complex processes. One of Kessler’s hypotheses about pollen tube reception is related to plant disease resistance and could eventually have a big impact on plant breeding.

Kessler’s lab has found a gene involved in pollen tube reception that is a member of a family of proteins that were originally discovered in research related to plant disease resistance – specifically in resistance of barley to a fungal pathogen called powdery mildew. Just like a pollen tube must communicate with the female plant tissue before it bursts, the pathogen must communicate with a plant cell before it invades.

If a plant has this gene, it’s susceptible to the pathogen. If the gene is mutated, the plant becomes resistant to the pathogen, but it also can’t receive pollen tubes, which means it can’t reproduce. Kessler and her lab are working to provide more evidence in support of this hypothesis.

“We need to understand this because we’re always trying to make plants more resistant to pathogens, but in doing that, you could also unintentionally affect reproduction,” said Kessler. “It’s definitely something to think about.”

Kessler’s lab is devoted to understanding how plants “talk” to one another and how that can affect plant reproduction. Although pollination may seem like a simple biological process, there’s much more to it than meets the eye. And sometimes, there’s even a romantic story involved if you take the time to look.

Faculty Profile Page: https://ag.purdue.edu/

The Kessler Lab website: http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~kessles/index.html