New field crops pathologist hits the ground running

“The hardest part for me,” said Darcy Telenko, “is being from a farm and knowing the impact. Knowing what it feels like when a farmer had a great crop, and a new disease emerges that impacts the final harvest and their bottom line. When talking about tar spot, I am honest with our Indiana farmers there are currently more questions than we have answers. I want to give them good, research-backed information, but we just don’t have it yet. Hopefully, we will soon.”

Telenko grew up on a dairy farm in New York but was never interested in the cows. She preferred tending to the vegetables that her family grew for their farm market. “That’s how I knew I wanted to do plant science research, even before I went to college.”

Telenko served as the Extension vegetable specialist at Cornell University before joining Purdue as an assistant professor of botany and plant pathology in August 2018. Soon after she arrived, tar spots emerged as a serious threat to corn in the American Midwest.

“There’s nothing like starting a new job in field crop pathology right as a new disease hits corn,” said Telenko. “I definitely wasn’t expecting that. I didn’t know anything about tar spot when I first started, but it gave me a unique opportunity to take the lead on something right away.”

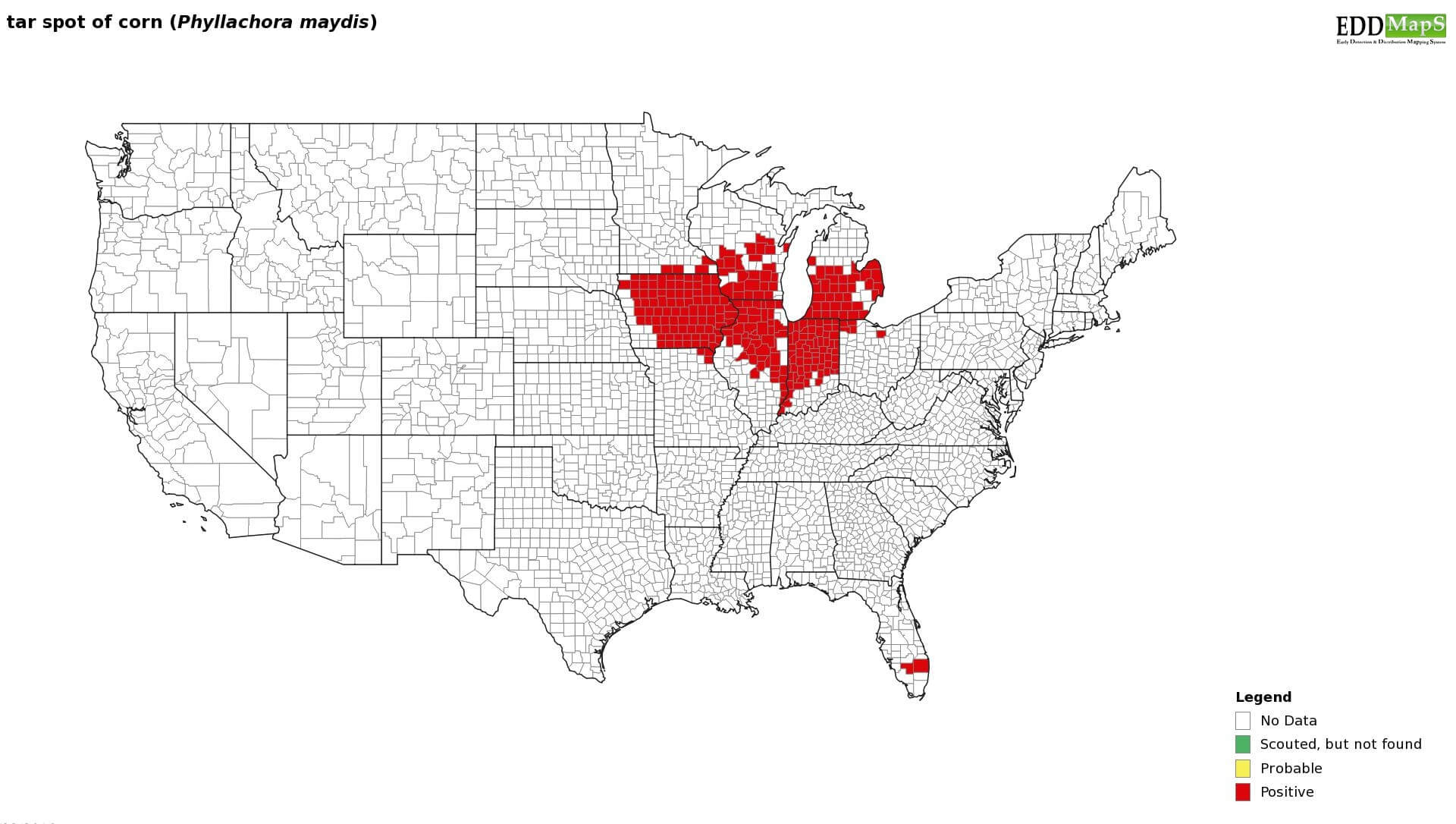

Tar Spot has a long history in agriculture but was new to Indiana. For over 100 years, a tar spot complex had a significant impact in Latin America, some areas losing over half their corn in a season. Tar spot had not been identified in the United States until 2015 when it was first found in Indiana and Illinois.

“Initially tar spot wasn’t of concern because only one of the two pathogens associated with the tar spot complex in Latin America was identified,” said Telenko. “It was also found later in the season as the corn was already reaching maturity resulting in little to no yield impact, but 2018 proved us all wrong.”

She quickly gathered preliminary data to measure the disease’s effect on yields. “Unfortunately, it’s easy to see the impact when some growers are losing 20 to 60 bushels an acre,” Telenko said.

Telenko has just finished harvesting corn from the 2019 field season where she had various research trials out to evaluate management options for tar spot. This includes fungicides for efficacy.

“Making a timely and effective fungicide application is going to be important since most fungicides available are only active for 14 to 21 days, meaning farmers must detect tar spot early and time the application precisely.”

“I’ve looked for tar spot so much that I close my eyes and see it, but it was still like a needle in a haystack when I first found it this year. I was in a field for over 30 minutes scouting and ready to quit right before finding a single black stroma at knee level.”

To make detection faster, Telenko is working with Christian Cruz, an assistant professor of botany and plant pathology.

“We cannot forget that this is a connected world,” said Cruz. “What we understand about the happenings at the disease’s origin is going to help us find solutions to use here. We rely on collaboration because one single group cannot do everything.”

In 2017, we were doing research in South America on a different emerging disease, wheat blast,” said Cruz. His team collected ground truth information from experts walking the fields and compared the data with UAV imagery. “That’s when things became very interesting,” said Cruz. “I started plotting and making correlations. It was not perfect, but there were very particular trends.” In 2019 his group published final results associated with the temporal dynamics and digital disease measurements of this emerging disease.

Cruz began to modify the wheat blast protocols and models for Telenko’s research, planning to utilize UAVs in a similar fashion.

Telenko values such partnerships, whether brainstorming with Cruz, comparing trial results with peers in neighboring states, or educating farmers through Extension.

“The only way we know what’s happening is to work closely with the farmers,” said Telenko. “Going and visiting farmers gives us a glimpse of the problems they are being faced. I can’t make it everywhere, but we have the Extension Network and Extension Educators in all 92 counties.”

“Five years from now, I hope I can tell those farmers, ‘We’ve found integrated management tools that will help you save 50 bushels an acre when tar spot is active.’ Those are the kind of thoughts that drive me. That’s what brings joy to my job.”