Purdue team introduces advance in automatic forest mapping technology

How lightning travels from the sky to the ground inspired the concept behind a new algorithmic approach to digitally separate individual trees from their forests in automatic forest mapping.

“When lightning travels from the sky to the ground, it finds the path of least resistance through the atmosphere,” said Joshua Carpenter, a PhD student in Purdue’s Lyles School of Civil Engineering. That led him to think the same way of his digital forest data, or point cloud.

“If I could somehow treat all of the points in this point cloud like a path of least resistance, that will tell me something about where the tree is located,” Carpenter said. The concept also works from a plant biology standpoint.

“Every leaf in a tree needs to be supplied with nutrients, and nutrients come from the ground. So, we find the shortest route for tree nutrients from the canopy down to the ground.” Carpenter and four Purdue co-authors published the details of their mapping methods recently in the journal Remote Sensing. The approach means the difference between mapping a few trees to mapping hundreds of acres at a time quickly and with high accuracy. It also could lead to making digital twins of forests, which could improve management planning in the face of climate change, disease outbreaks and population growth.

The work was partially supported by Purdue’s Integrated Digital Forestry Initiative. This initiative, one of the five strategic investments in Purdue’s Next Moves, leverages digital technology and multidisciplinary expertise to measure, monitor and manage urban and rural forests to maximize social, economic and ecological benefits.

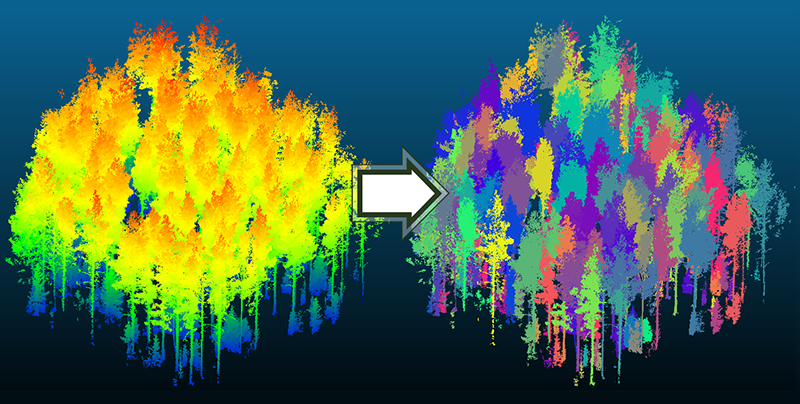

This image shows the input and output data of the tree segmentation algorithm. The input data (left) is colored by elevation. The results of the algorithm (right) use color to segment each tree from the point cloud.

This image shows the input and output data of the tree segmentation algorithm. The input data (left) is colored by elevation. The results of the algorithm (right) use color to segment each tree from the point cloud.

“We developed a new individual tree segmentation algorithm that can be used to do tree inventory for large areas,” said article co-author Jinha Jung, assistant professor of civil engineering. Carpenter is a member of Jung’s Geospatial Data Science Laboratory, which specializes in mapping and measurement.

“Another contribution of this paper is how to evaluate the performance of the segmentation algorithm with data collected from the ground,” Jung said.

The algorithm has proven more highly accurate according to most metrics, often by a wide margin, when compared to the current state of the art. Validation involves directly tagging and measuring individual trees in the field to correlate with LiDAR data collected at the ground level and aerially at different times of the year to capture trees that are leafy and leafless.

The team is still addressing issues arising from their three data collection methods: photogrammetry (creating 3D imagery from 2D photographs) and two types of LiDAR (aerial and ground-based).

Data in the point cloud have the same structure, but the data from each method contain different anomalies. One might capture tree canopy top details quite well but miss elements of the trunk and vice versa. Sometimes features in the landscape block data collection, too.

“The goal is to use all of the different point clouds that are available to make a flexible algorithm,” Carpenter explained. “But coming up with a method to work with each of the specific anomalies is challenging.”

Working in the 400-acre Martell Forest about 8 miles east of campus, the Purdue team continues to broaden the scope of its technology.

“How can we get from several hundred acres to several thousand or several hundred thousand, and then to every tree on the planet? That’s the future,” said article co-author Songlin Fei, professor and Dean’s Chair of Remote Sensing in Forestry and Natural Resources. “The issue is how to scale it up.”

Taking inventory requires tedious fieldwork to sample 5% or 10% of an area. “A 100% inventory has never been an option. This paper is demonstrating technologies that allow a census of every single tree. We’re talking about a tremendous leap,” Fei said.

The Remote Sensing paper focuses on forest mapping, but more algorithms will be needed to achieve complete inventories.

“We can do diameter measurements with this data. But how about other key inventory features, like straightness, timber grade or species identification? Those are yet to be accomplished,” Fei said.

The technologies now make it possible to produce a digital twin of an entire forest to see the potential effects of an ice storm or high winds.

“If you do a forest management plan, you cannot just harvest the trees and see how it looks,” Fei noted. “But in the digital world, you can cut any tree you want, and you can put it back. That allows you to do simulations and better management planning.”

In recent decades, geospatial data have vastly increased agricultural production. The Purdue researchers seek to do likewise for forestry, a source of important raw materials for construction and fuel. Catastrophic wildfires and invasive species that have wiped out large stands of American chestnut and ash trees now focus attention on the importance of forests.

“We have applied all these technologies successfully to agriculture,” Carpenter said. “But other domains now need our attention.”