Ag faculty member devising new drug delivery tactic for citrus greening disease

Purdue University’s Kurt Ristroph has received a $1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture to develop nanocarriers as an antibiotic delivery system to help plants fend off citrus greening disease.

More formally known as Huanglongbing (HLB), citrus greening disease has left the Florida citrus industry in nearly total ruin since 2005. Spread by the Asian citrus psyllid, an insect that resembles aphids, the disease also has afflicted citrus trees in California and Texas.

“The mixing technology we’re using to make nanocarriers is the same that has been used by pharmaceutical companies like Pfizer,” said Ristroph, assistant professor of Agricultural and Biological Engineering. Collaborating on the project with Ristroph are Greg Lowry, Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh; Arnold Schumann, University of Florida; and Philippe Rolshausen, University of California, Riverside.

HLB bacteria live inside the trunks and roots of trees, attacking their vascular systems. Previous attempts to kill the bacteria with antibiotics have failed.

“It’s difficult to reach the location in the tree trunk where the bacteria live,” Ristroph said. The bacteria live in the phloem of a tree’s vascular system.

“Humans have veins and arteries. Plants have xylem and phloem,” Ristroph explained. One approach has been to bore a hole into the tree trunk and inject the antibiotics with a syringe, “but you don’t have a good guarantee that you’re going to the phloem. And if you don’t, then you’ve just done a lot of damage to your tree.”

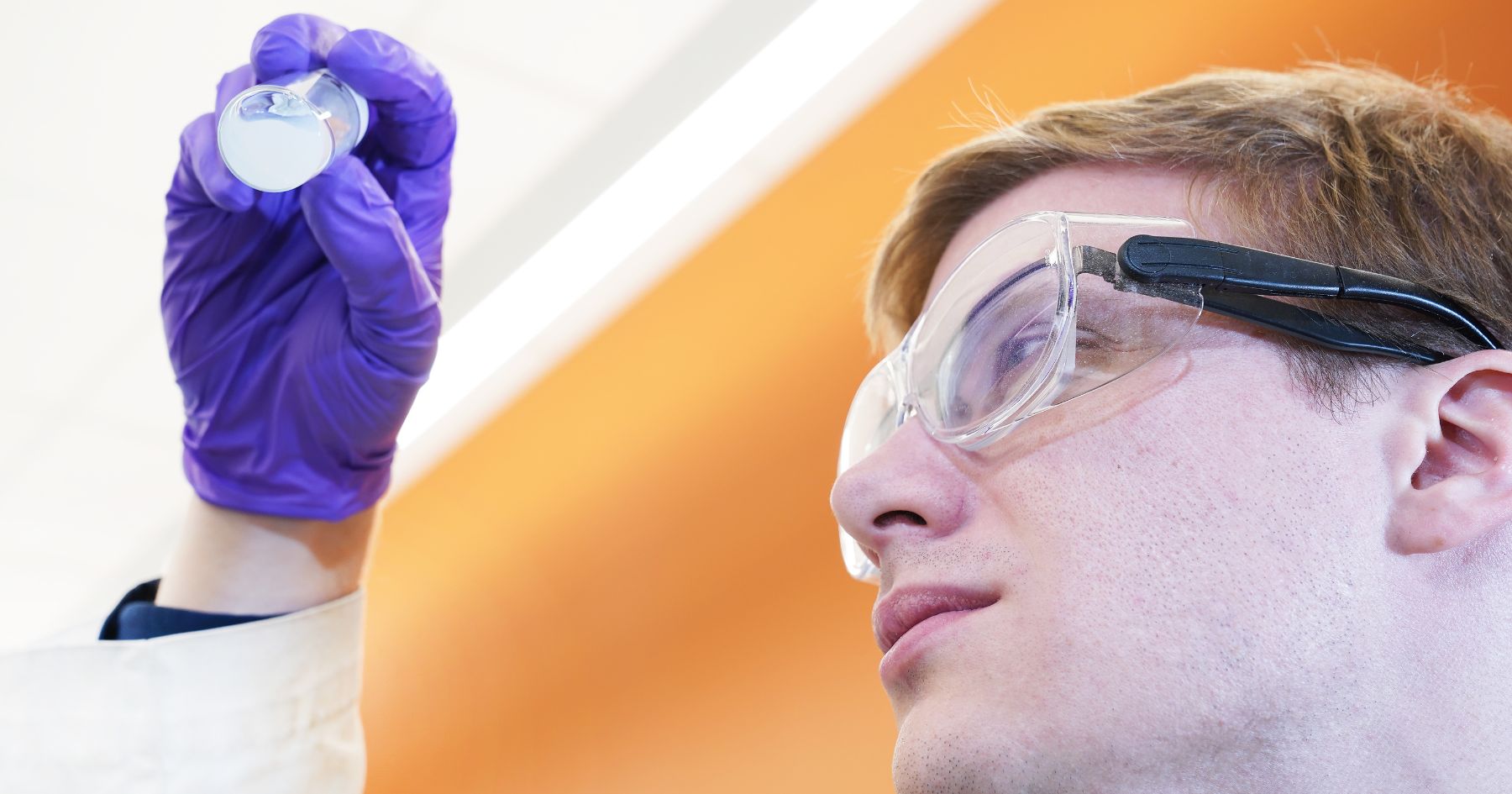

Kurt Ristroph, assistant professor of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, holds two vials of nanocarrier treatments being tested for treatment of plant diseases. (Photo Credit: Tom Campbell)

Kurt Ristroph, assistant professor of Agricultural and Biological Engineering, holds two vials of nanocarrier treatments being tested for treatment of plant diseases. (Photo Credit: Tom Campbell) Another issue: the bacteria live in the phloem of both the trunks and the roots. But if an injection kills only the bacteria in the trunk, they can repopulate from the roots back into the tree.

“We’ve shown that our nanocarriers, at least in another plant system, can get into the phloem and down to the roots. If we make our nanocarriers encapsulate an antibiotic that will kill this disease, then put them on the leaves of a tree. We think they’ll go inside the tree, down the phloem to the roots and they’ll release their antibiotic drug along the way. Maybe it can kill all the bacteria and maybe it can cure the disease,” Ristroph said.

Ristroph completed his Ph.D. in chemical engineering and materials science at Princeton University. He specialized in pharmaceutical formulation—packaging an existing drug molecule into a new form to improve its function. If a drug doesn’t readily dissolve in the mouth, for example, the drug can be reformulated into a form that can be given orally.

At Princeton, Ristroph developed nanocarriers for human drug delivery. He used a technology called “Flash NanoPrecipitation” that his Ph.D. adviser, Robert Prud’homme, developed as a large-scale way of making nanocarriers. The nanocarriers consist of a core—the drug awaiting delivery—and a shell that encloses it.

After completing his Ph.D., Ristroph became a Schmidt Science Postdoctoral Fellow. Schmidt Fellowships are designed for scientists who wish to switch from their Ph.D. field into another specialty.

“My proposal for the postdoc was to pivot from human drug delivery to plant drug delivery, to see if this large-scale formulation for making drug nanocarriers can be used in agriculture,” Ristroph said. “And it’s not just drugs for plants. Plants need all kinds of agrochemicals. They need fertilizers and pesticides, hormones and sometimes antibiotics.”

During his postdoctoral research with Greg Lowry at Carnegie Mellon, they obtained some promising preliminary data suggesting that nanocarriers made by Flash NanoPrecipitation can get into plants and move around. They began to look for an incurable plant disease and came across citrus greening. So now, with the USDA grant, Ristroph and his collaborators will work to use nanocarrier formulations for drug delivery to plants rather than people. Many challenges still await.

“We’re using antibiotics that have already been approved for citrus greening. We have to get them where they need to go in the plant,” he said. “We’re going to have to be incredibly effective to show that we can cure the trees.”

Ristroph’s efforts are driven in part by his family’s agricultural background in southern Louisiana, where his parents own and operate a sugarcane farm.

“As we were working on this process in grad school, I was thinking, this is really large scale and it’s low cost per unit. I wonder if this could do some good in the ag world?”

Ristroph received the USDA grant only two months after he joined the Purdue faculty last August. Already he has already built a research group consisting of one postdoctoral scientist, three graduate students and two undergraduates. Half the group works on drugs for plants, while the other half works on drugs for people.

“I’m very fortunate because there’s a lot of work to do,” he said.