What Purdue researchers learned from the 2024 eclipse

While most vehicles driving towards the path of totality in the 2024 solar eclipse were loaded with family, friends and enough snacks to get everyone through hours of bumper-to-bumper traffic, Purdue Agriculture researchers had already filled their cars with recorders, microphones, bees, plexiglass hives and set off to set up to observe and listen to the impact of the eclipse.

The labs of Bryan Pijanowski in Forestry and Natural Resources and Brock Harpur in Entomology traveled south to reach the path of totality a week in advance to set up their equipment.

Pijanowski, who studies the sounds of nature and how they change over time and under different conditions, had scouted out a wetland at Southeast Purdue Agricultural Center (SEPAC). Marshes and bogs offered promising soundscapes: frogs croaking, birds chirping and the babbling flow of water as fish rushed past. The lab members set up recorders across the woods and waters a week ahead of time to listen in to the local environment both before and during the eclipse.

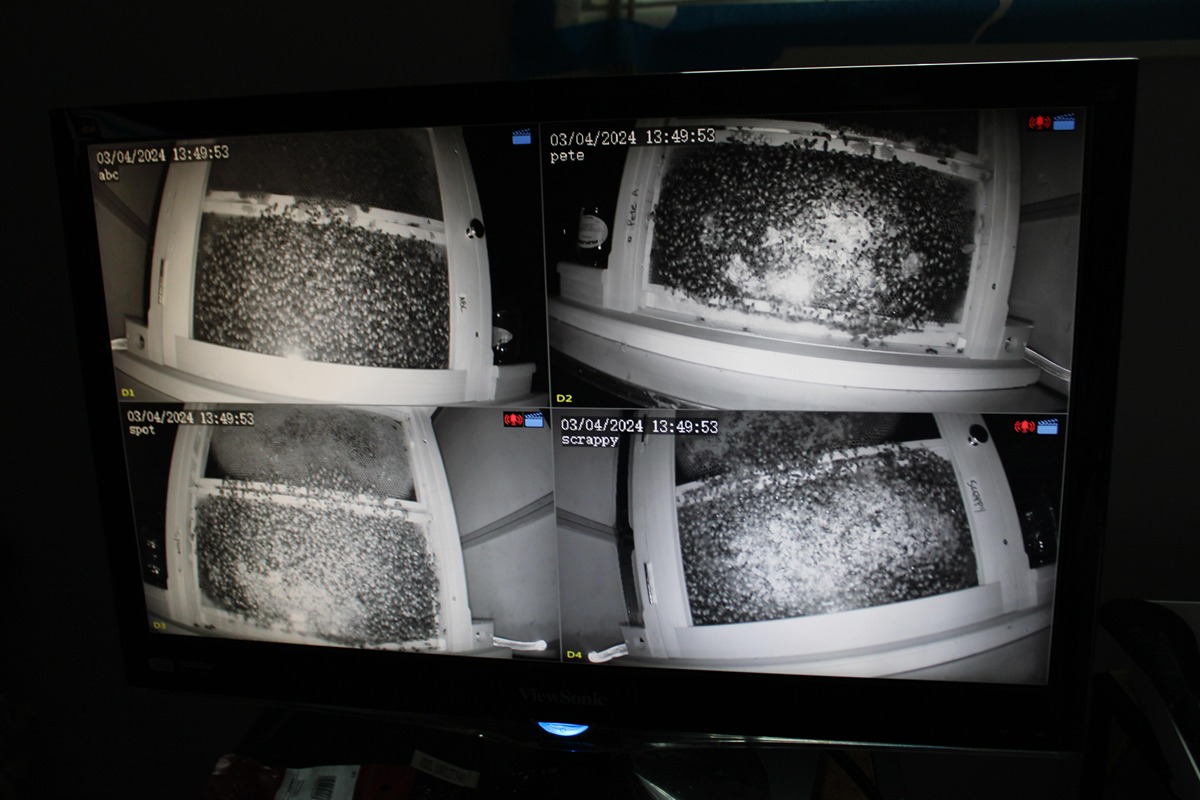

An urban location was chosen for the entomology lab focused on honey bees. Harpur’s students established glass observational hives in a garage in Bloomington, Indiana, the week before the eclipse.

“Our project is part of a nationwide effort led by Barrett Klein at the University of Wisconsin La Crosse. There haven’t been any scientific studies on the behavior of bees inside their colony during an eclipse,” Harpur said. “We didn’t know how honey bees would respond to this celestial event.”

For graduate students like Izaak Gilchrist and Sam Lima, experiences like this are guiding forces for future research directions.

For graduate students like Izaak Gilchrist and Sam Lima, experiences like this are guiding forces for future research directions.

Lima, from Pijanowski’s lab, had watched the 2017 eclipse from Baltimore. Driving to SEPAC with her labmates, though, was on another level. While half of the lab went down to the water, she and a few others climbed to the top of a hill and listened from a clearing formed by two intersecting trails.

“It was a different experience from being downtown in the middle of Baltimore versus sitting in the middle of the woods,” Lima said.

The most exciting part of being in the wetlands to Lima was the frogs. “There are these little frogs called spring peepers, and they’re not usually active when the sun is out. But when it got really dark, the frog chorus was loud. I just recently learned which sounds were spring peepers, so it was cool to hear them come out and know what they were.”

Unfortunately, the frogs weren’t the only loud things that came out in totality. Viewers across Indiana set off fireworks to celebrate the occasion, which overcrowded the sounds on much of the Pijanowski lab’s recordings. While this makes the recordings difficult to use for further analysis, Lima is certain that there is still plenty of good data from the week leading up to the eclipse that her lab can use.

Pijanowski also said that their personal observations would be useful for future research directions. “We saw fish jumping out of the water at a much greater rate during totality than before and after. Is this because they thought it was night, or did the insect patterns change?”

Lima has been studying rangelands and grazing patterns in Mongolia, and watching the eclipse has reaffirmed her motivation to study the day-and-night cycles of sound in those pastures.

For Harpur’s lab, visual observations were more important than sounds. They aimed infrared cameras at the plexiglass-walled hives to watch honey bee activity inside of the colony, looking specifically for worker bees making figure-eight patterns and shaking their bodies rapidly.

Graduate student Gilchrist explained that this was their waggle dance. “Bees have a waggle dance when they come back from foraging to tell other bees where they found a good resource, usually food. They convey a lot of information with this waggle dance, like the distance of how far away this food source is. And they'll dance more vigorously if they think it’s a really good spot.”

The angle of this dance is also very important for other worker bees to find the resource. They use the position of the sun in the sky as a compass to show the bees which direction to take. The nationwide effort asked how the waggle dance would change as the total solar eclipse took their compass out of the sky and how the darkness of totality would affect bee circadian rhythms.

how the darkness of totality would affect bee circadian rhythms.

During totality, Gilchrist and her lab colleagues observed bees flocking back to their hives. It will be up to their collaborator Klein to analyze the videos of the bees to see how the waggle dance changed. But Gilchrist saw changes in the hives that are relevant to her own research on drones—or male honey bees.

While worker bees tend to be kicked out of a hive if they fly into the wrong one, drones can be allowed into different hives, even if they don’t breed with the bees there or provide any benefit that humans can yet perceive.

“We did see some weird stuff with drones during the eclipse,” Gilchrist said. “When we brought in the observation hives, there were not many drones in them. A few days after the eclipse, we were seeing a lot more drones, and they definitely were not reared in those colonies. They weren't there for long enough. So, we think that drones from a nearby beekeeper got in.”

Beyond the research implications, Gilchrist was excited to join her lab for the major event. Figuring out how to transport bees, hives, and reinstall them in the darkness of a garage while still observing them was a challenging task. Although she led the charge and became the “Eclipse captain” for her team, she gives credits to her labmates, especially Stephanie Hathaway, who found a place for the bees in Bloomington and took photos every step of the way.

The total solar eclipse was fast, fleeting and full of uncontrollable environmental conditions. But, both the Pijanowski lab and Harpur lab found points of interest to study, something researchers won’t be able to do in Indiana again until 2099.