Contaminants in the cold: How everyday chemicals are affecting Antarctic fish

Antarctica, once seen as a pristine wilderness, has trouble brewing in its waters.

As researchers, tourists and military personnel venture to the region in growing numbers, they’re leaving behind more than just footprints. Human waste and pollutants, including pharmaceutical and personal care products (PPCPs), are making their way into the icy waters of Maxwell Bay – with potentially lasting effects on the region’s delicate ecosystem.

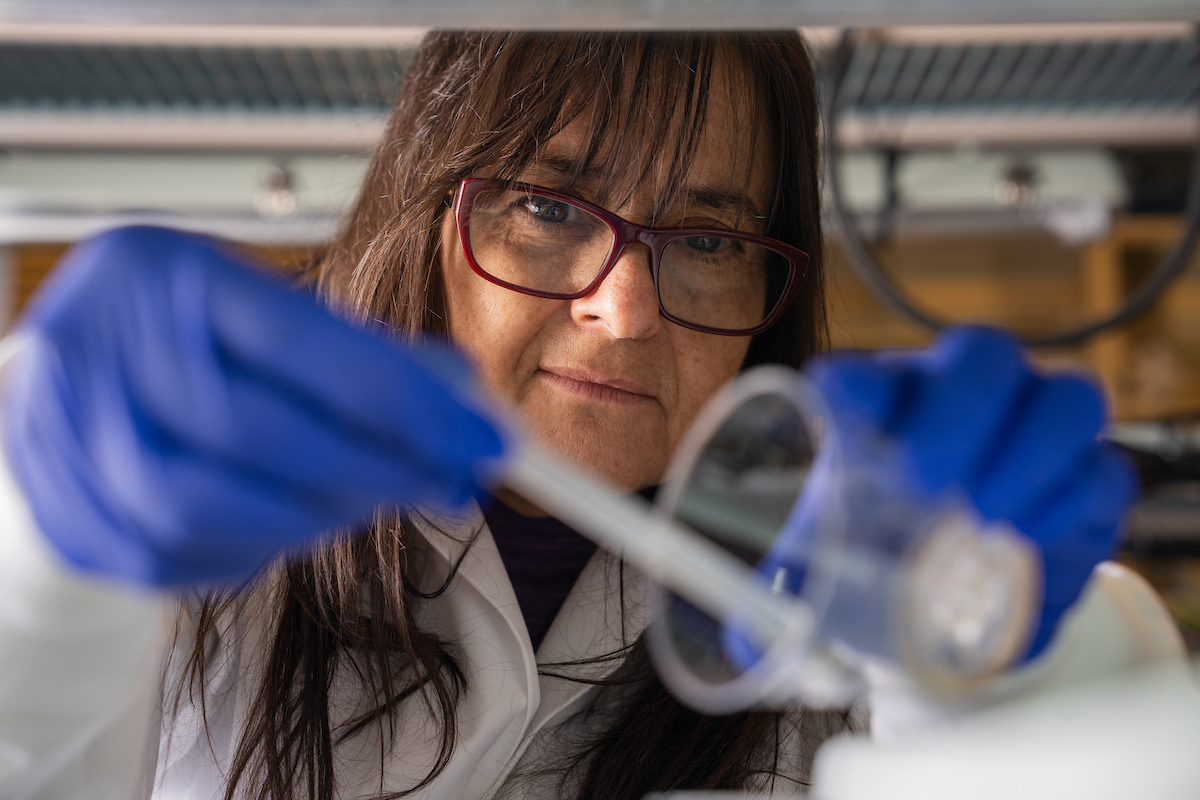

Ecotoxicologists Maria Sepúlveda from Purdue University’s College of Agriculture and Paulina Bahamonde from the Universidad Mayor Center for Resilience, Adaptation and Mitigation in Chile, are leading a study on how PPCPs affect the Antarctic spiny plunderfish (Harpagifer antarcticus), a key bioindicator of pollution’s impact on marine organisms.

Now in its third year, the project, “Endocrine disrupting consequences of pharmaceutical and personal care products on the Antarctic fish Harpagifer antarcticus: influence of human settlements and scientific research” (FONDECYT 1230485), is funded by the National Research and Development Agency of Chile and receives logistical support from the Chilean Antarctic Institute (INACH).

This research sheds light on human impact in one of the world’s most isolated ecosystems and highlights the urgent need to protect Antarctica’s fragile environment.

The growing human presence in Antarctica has been driven by rising temperatures and technological advances, making the continent more accessible. Maxwell Bay, located between King George and Nelson Islands, is home to several permanent research stations, an airport, and cruise ship traffic.

“Before, people could only visit Antarctica during the summer,” said Bahamonde, the project’s principal investigator. “Now they are there year-round.”

The Madrid Protocol, in effect since 1998, enforces strict environmental protections in Antarctica. Most research stations use primary wastewater treatment, separating solid and liquid waste, and some add chlorine to kill bacteria like E. coli before releasing effluent into the bay.

Even treated wastewater contains pollutants like PPCPs—including medications, soaps, lotions, and other hygiene products. Many of these chemicals act as endocrine-disrupting compounds (EDCs), which can alter metabolism, suppress immune function, and affect reproduction in marine life.

Under normal conditions, PPCPs degrade quickly, but Antarctica’s frigid waters may slow the process. The continuous influx of sewage-derived chemicals could lead to long-term exposure for marine organisms.

“These chemicals are broken down by bacteria,” explained Sepúlveda, professor of ecotoxicology and aquatic animal health in the School of Forestry and Natural Resources. “We expect that process to be a lot slower in freezing temperatures.”

To understand the effects of PPCPs on Antarctic marine life, Bahamonde and Sepúlveda are studying the Antarctic spiny plunderfish. This species is abundant in Maxwell Bay and has a very limited habitat, making it an ideal bioindicator of local contamination.

“They’re easy to collect – you can just pick them up with your hands,” Bahamonde explained. “Since they don’t move much over their lifespans, we can link their condition directly to their location.”

The study focuses on several locations along the Fildes Peninsula, with water and fish samples taken near several permanently occupied research bases. They also use reference samples from Collins Bay, upstream from human activity, and Nelson Bay, across from the inhabited region.

The research effort spans the eastern hemisphere. In Antarctica, Bahamonde gathers fish tissue samples—brain, gonads, and liver—for analysis in her Chilean lab. Sepúlveda, the only U.S.-based researcher on the team, helps to analyze and interpret the transcriptomic data at Purdue.

The chemical analysis of water requires specialized equipment unavailable in Chile. The team initially worked with a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) lab and are now partnering with Mark Servos, professor and Canada Research Chair in Water Quality Protection at the University of Waterloo in Canada, for further testing.

Sepúlveda will soon travel to Antarctica to collect more water samples to track chemical levels in the bay over time – and she may even don a wetsuit to catch plunderfish herself.

Early findings from the study reveal that fish from contaminated areas show weakened immune systems and increased parasite loads compared to those from cleaner waters. They also exhibit endocrine disruptions, such as smaller gonads and hormonal imbalances.

“A lot of these chemicals are estrogenic,” said Sepúlveda. “For example, vitellogenin, a protein normally found only in females, appears in males exposed to PPCPs.”

Bahamonde likens these effects to human reproductive issues like polycystic ovary syndrome, early puberty and declining sperm counts. While these effects aren’t inherited, they can reduce fertility and impact populations over time. They might also be passed on to animals that prey on fish from polluted waters, like penguins or marine mammals.

As expected, PPCP levels are highest near heavily occupied research stations. But even uninhabited sites contain traces of contamination, carried by glacial melt and currents around the bay. The exception – one base that shipped its waste back to its home country, rather than releasing it into the water.

Though the project is only funded through 2026, both Bahamonde and Sepúlveda believe their work is just beginning. The ecotoxicologists want to explore how sewage treatment affects gene resistance in bacteria that can break down PPCPs and how PPCPs may affect other biological components of this fragile environment.

“People talk about microplastics, persistent pollutants and pesticides, but PPCPs don’t get the same attention,” said Bahamonde. “Our research can help protect Antarctica’s unique ecosystem.”

This research is a part of Purdue’s presidential One Health initiative, which involves research at the intersection of human, animal and plant health and well-being.