Sticking together under stress: NSF grant brings plant biologists and engineers together to discover how tissues stay connected

Staring up at redwoods and giant sequoias, or even the rose bush in your backyard, it’s hard to imagine that all plant life began as small sprouts. Plants come in different shapes, sizes and textures to color the world around us. Evolution drives this diversity of nature, but it is created by a complex network of mechanical forces that hides beneath our noses, in play within every developing bud, leaf, stem and root.

All cells — human, bacteria, yeast, plants — need to sense mechanical signals that are intrinsic to their development. Forces on and within cells are decoded to sense their own size and shape and get an accurate read on what their neighbors are doing. There’s this whole world of mechanical signaling that’s been really difficult to study because those forces are invisible, hard to measure and the molecules that sense forces are largely unknown.”

- Daniel Szymanski, professor of botany and biology

Plant cells have a thick wall on the outside, protecting them and defining the patterns of growth. The cell wall is made of tough materials with finely tuned physical properties. Plant organs, like a leaf, dynamically sculpt these materials in each cell.

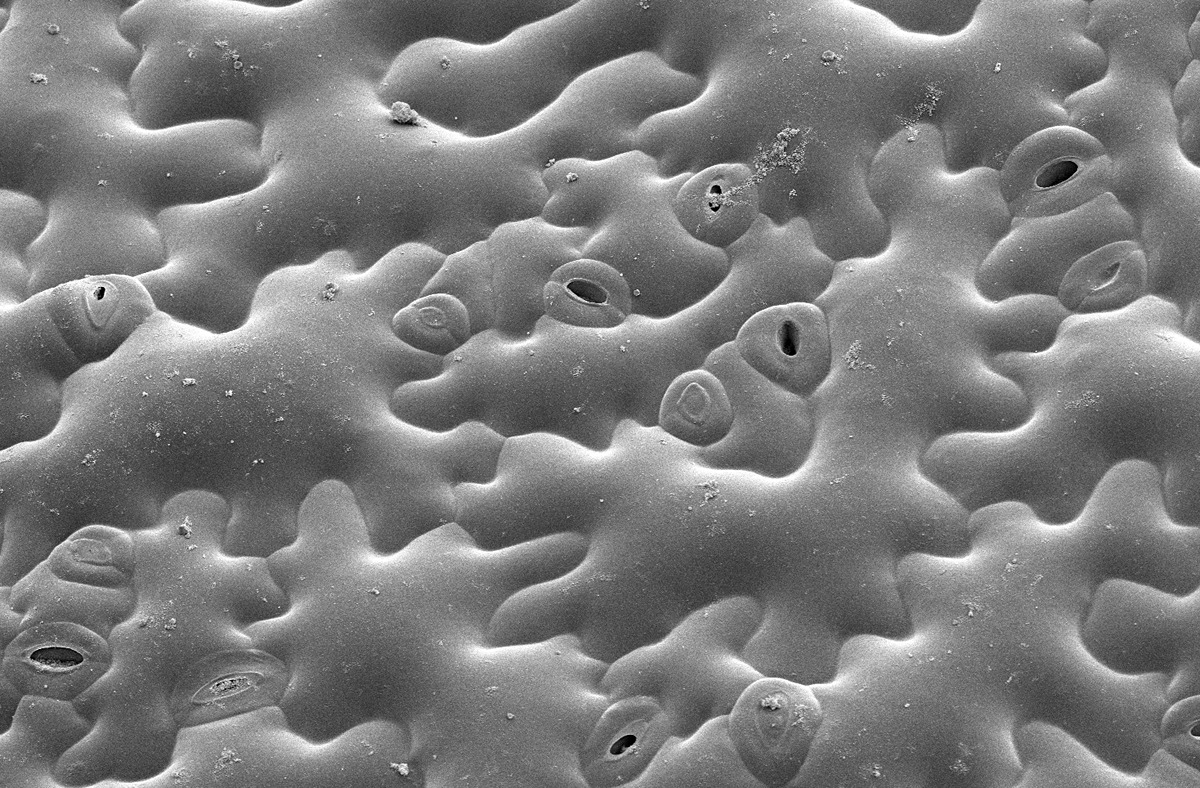

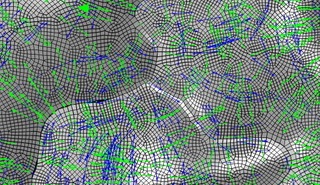

The outermost layers of cells in a leaf, called the epidermis, exert strong controls over the leaf to determine its patterns of growth. In leaves, it forms a functional, complex network of jigsaw puzzle piece-shaped cells that cooperate as a unit to define growth behaviors of specific cells and of the leaf as a whole. (Photo provided by the Szymanski lab.)

The outermost layers of cells in a leaf, called the epidermis, exert strong controls over the leaf to determine its patterns of growth. In leaves, it forms a functional, complex network of jigsaw puzzle piece-shaped cells that cooperate as a unit to define growth behaviors of specific cells and of the leaf as a whole. (Photo provided by the Szymanski lab.) Plant cells are “glued” to each other, yet they are constantly growing. The high internal pressures of plant cells generate strong and multi-directional forces in the cell walls to drive growth. A cell senses stress, and it adapts the wall composition to better support the leaf and stay connected to the rest of the epidermis. If this cell to cell adhesion fails, the entire developmental system falls apart, the plant loses water and dies.

Daniel Szymanski, professor of Purdue’s Departments of Botany and Plant Pathology and Biological Sciences, and Thomas Siegmund, professor in Purdue’s School of Mechanical Engineering, as well as Chelsea Davis, associate professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware, recently received an $1.1 million award to Purdue and a $345 thousand award for the University of Delaware from the National Science Foundation to advance knowledge on plant cell adhesion.

Szymanski’s lab analyzes epidermal development and how cells in a tissue stay connected using mutant plants that have a malfunctioning epidermis. By identifying genetic control pathways and analyzing gene function using real-time high resolution live-cell imaging, his team is discovering how plant cells sense destabilizing forces in the tissue and then reinforce cell to cell adhesion at locations of mechanical instability.

“The genes and protein machinery that enable tissues to remain intact during development aren’t known. The forces that destabilize the tissue have never been quantitatively analyzed,” Szymanski said. “This is why we formed an interdisciplinary team.”

To measure these mechanical forces and reveal how cell to cell adhesion works, Szymanski had to work with engineers and materials scientists.

Siegmund is an expert in the analysis of adhesion and fracture. His team constructs computational mechanical models that simulate plant cells and their mechanical behavior using a tool called the finite element method (FEM). The computational models reliably predict mechanical forces in and across the cell walls, providing insights into important forces for plant development.

team constructs computational mechanical models that simulate plant cells and their mechanical behavior using a tool called the finite element method (FEM). The computational models reliably predict mechanical forces in and across the cell walls, providing insights into important forces for plant development.

Equations of elasticity predict how cells deform and adhere to each other and then break away, and they are too complex to be solved analytically. The FEM divides the cell walls into several building blocks, called elements. Solving equations of elasticity for individual elements and assembling those into a patch of cells is doable with the FEM.

“In my lab, we have long studied adhesion between engineering structures,” Siegmund said. “We bond one component to another and question how strong and tough such an attachment is. We can now apply the mechanics of adhesion in engineering to the mechanics of plant cells to better understand the plant cell assemblies and the long term stability of plant cells.”

The models can make specific predictions about how a leaf epidermis operates, where the forces are most greatly expressed and how the cell senses and responds to them. Szymanski can then test those theories in his lab with real Arabidopsis thaliana plants. FEM, however, has to be developed using accurate data on the strength and toughness of cell to cell interactions, which are difficult to measure.

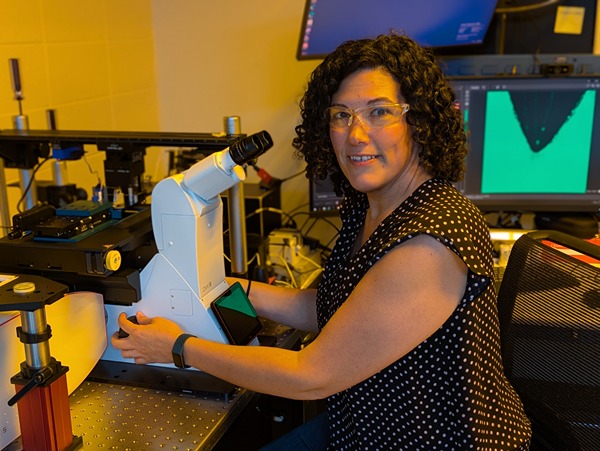

Most engineers study material properties on a large scale, pulling on big objects and testing how much force is required to stretch or tear it — not something only millimeters wide like a young Arabidopsis leaf. Luckily, Szymanski connected with Davis, then a professor of materials science and engineering at Purdue. Davis is an expert in testing tiny structures for their properties, using specialized tools to do it under a microscope.

Most engineers study material properties on a large scale, pulling on big objects and testing how much force is required to stretch or tear it — not something only millimeters wide like a young Arabidopsis leaf. Luckily, Szymanski connected with Davis, then a professor of materials science and engineering at Purdue. Davis is an expert in testing tiny structures for their properties, using specialized tools to do it under a microscope.

Davis and Szymanski formed an interdisciplinary collaboration and were funded by a National Science Foundation Transitions to Excellence grant. They each hired a postdoctoral researcher who would start out in one lab and eventually switch to working in the other’s lab to continue the project.

“The collaboration included bidirectional learning, where the engineers now understand the biomechanics of plants, and I’ve learned enough about their expertise for us to be able to communicate and participate as a diverse team,” Szymanski said.

For Davis and her lab, the project has been an exciting exploration into where their skills and technology can be applied to make a real difference.

“I’m talking to a bunch of prospective students that want to join my lab about this work. They are so eager to think about how we can make measurement tools and apply our understanding of mechanical engineering and material science to a biological system,” Davis said. “Students coming into grad school today want a PhD, but, more importantly, they want tools that will let them solve the problems of the world.”

In Davis’ lab at the University of Delaware they grow the Arabidopsis seeds sent by Szymanski until they are sprouts with two leaves, called cotyledons. These circular leaves are only a couple millimeters across and are pulled apart by micromechanical grips underneath the microscope.

“We were able to measure how hard it was to pull apart, how far we had to stretch it before it pulled apart, and we also watched how it separated,” Davis said, and noted that such data might be useful in agriculture’s fight to feed the world.

Szymanski explained, “In the last 10 years, we’ve been bringing in the mechanical models, and the rate of deep insights into biomechanics and growth has been accelerated 10-fold or even 100-fold. This is game changing.”

While Siegmund’s mechanical engineering lab has researched biological systems like human soft tissue and bone, they had to learn the biomechanics of plants to be able to model what was going on in the epidermis. With Davis watching for where stress appeared on leaves under the microscope as she pulled them, Siegmund said, “We can directly compare the outcome of our simulations — predicted hotspots — to the measured hotspots. It’s a great way to compare a computer simulation to experiments.”

The foundational knowledge gained from this project goes beyond understanding how plants adhere to each other — it gives key insights for future plant breeding and biotechnology practices to make more resilient crops with specified variations in organ size and shape.

For the students involved in the project, the research also trains them to understand both fields and build careers out of that combination. Davis shared that one of the postdoctoral researchers under the transitions grant has now works for the company that builds the measurement tools her lab uses and is expanding the engineering-minded business into botany.

“Because former postdoc Michael Wilson can speak like a plant biologist now and has seen how you can apply mechanical deformation to this whole new field, he’s going to change their business model. It opens up a whole other category of customers to them, and it potentially brings some tools to the botany community that they didn’t have before,” Davis said.