Many stories have been told about people effected by travel bans both foreign and domestic due to COVID-19, but FNR graduate student Laura Jessup was in the thick of it, locked in Peru for several days after attending a workshop when the country’s president Martin Vizcarra closed the borders on March 15.

The trip may have been doomed from the start. A workshop studying how plant traits are affected by climate change and fire, was originally slated to take place in Chile, then the relocated event in Peru was shut down a week early as the country closed its borders due to COVID-19 concerns, stranding Jessup, a PhD student, and 26 other members of her class.

“The course was actually originally scheduled to be in Chile, but about the time they were finalizing the plans for it, Chile had real major political unrest, so they figured Chile wouldn’t really be safe anymore, so at the last minute they moved it to Peru,” said Jessup’s advisor Jeff Dukes, Professor of Forestry & Natural Resources & Biological Sciences and Director of Purdue Climate Change Research Center. “And then all of this happened. So, it was sort of a three-hour tour, if you get the Gilligan’s Island reference.”

Jessup, who is part of the ecological science in engineering interdisciplinary graduate program in addition to being an FNR student, first heard about the plant trait course from Dukes.

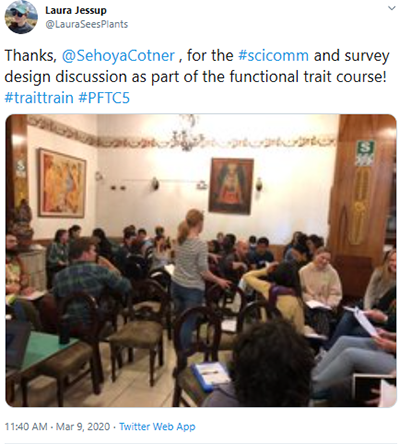

“The opportunity to get hands-on training in trait-based ecology was really exciting, as well as the opportunity to travel at the same time,” Jessup said. “Field work and traveling are two things that I love, so I was pretty immediately drawn to the idea of the class. The class wasn’t just field work, it was also learning how to do open science and learning how to analyze data and work with data and work with a team collaboratively. So, above and beyond just learning the measurement techniques in the field, I was very excited to learn how scientists work together over broad geographical areas. We had people from 12 countries there.”

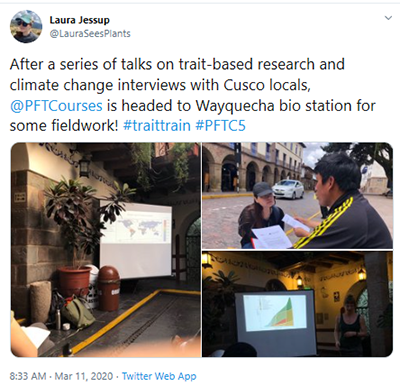

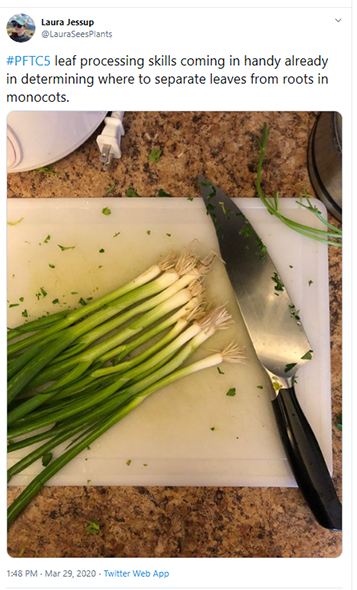

The workshop fit soundly within Jessup’s research on carbon storage. The DeWitt, Michigan, native is especially interested in roots ecology, below ground ecology and how and why plants allocate carbon to certain organs – whether roots, leaves or stems. The course looked at leaves across an elevation gradient, kind of a climate change gradient.

“As you move up the mountain and climate change happens, the elevation will be indicative of future environmental changes, so we can see what plant communities are like at this elevation vs. this elevation and that might tell us how plant communities are going to change,” Jessup explains. “We were specifically looking at how plant traits, specifically leaf traits might change due to climate.”

An ominous cloud began forming over the trip the day that Jessup was due to depart for Peru as an email was circulated from Purdue regarding the cancellation of university-sponsored spring break travel and study abroad trips.

“It was kind of disconcerting receiving an email from Purdue the morning I was getting on a bus to head to O’Hare,” Jessup recalls. “I technically didn’t fall into those categories, but I thought, ‘should I?’ In the back of my mind, I knew that there was a possibility that something like this could happen, but I think I was very optimistic that it wouldn’t get that bad in three weeks or whatever so I would be able to return on time. I think a lot of the participants in the course said the same thing… they knew that it didn’t seem quite right to be traveling but they were optimistic that it was going to be ok.

“One thing that Jeff (Dukes) said to me when I was still in Peru is that this is a good exercise in exponential thinking. We are very familiar with the idea of exponential growth especially as it relates to the coronavirus, with its perfect exponential curve, but our responses to that need to be exponential as well. We need to anticipate exponentially. So, instead of being cautious when I left, I probably should have just canceled the trip, which would have seemed extreme at the time, but looking back would probably have been the right thing to do.”

In spite of initial concerns, Jessup and 46 others made their way to Cusco, Peru, for the workshop and began their work in earnest, heading to a remote village three hours from Cusco in Manu National Park.

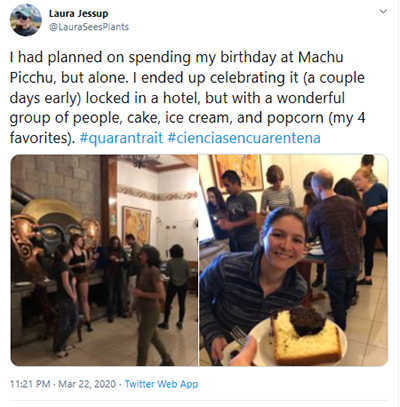

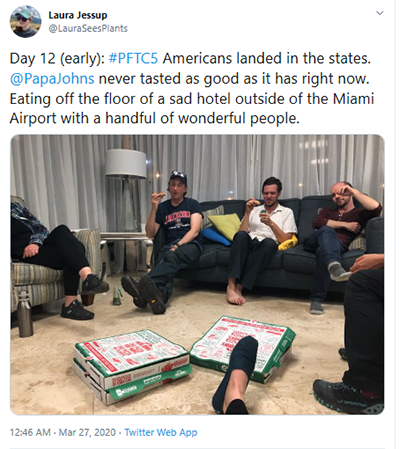

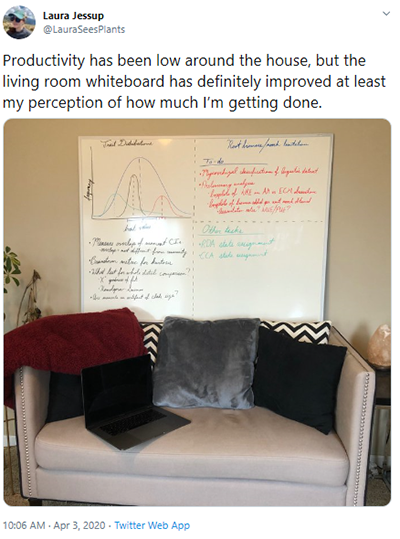

After giving herself time to process the saga and return to daily life, albeit once again in quarantine, Jessup has returned to science.

"At this point, I kind of miss them," Jessup retorts.

Jessup continues to keep her sense of humor as she retweets articles detailing her saga and those of many others still seeking to return home. Follow @lauraseesplants on twitter for more.