Kellner Tabbed with Osborn Early Career Award

All the knowledge is in the connections. – David Rumelhart.

As the son of two elementary school teachers, education was an important aspect of life for Dr. Ken Kellner. Growing up in a rural area of Buffalo, New York, and being home-schooled by his mother during his elementary school years, gave Kellner him the flexibility and freedom to play outdoors and learn about nature, which set the foundation for a career that has impacted the world of wildlife conservation and quantitative ecology.

Mrs. Reinhold, Kellner’s high school biology teacher, cultivated that love of nature and “opened my eyes to the idea that getting into science and being a researcher was something I could do as a job.”

As Kellner turned his attention to college, family ties guided him to Wheaton College in Illinois. Kellner followed in the footsteps of his parents and some of his grandparents, all of whom are alumni.

“There was a little bit of family pressure to go there, but it's a really good school and I wanted to go somewhere further away from home to try to be on my own, and the academics were excellent,” Kellner recalled. “I think I made the right choice; it was a great experience.”

Unknowingly, the choice to attend Wheaton also would set the trajectory for the rest of his academic career.

Kellner’s advisor at Wheaton was Dr. L. Kristen Page, who was named a Distinguished Ag Alumni Award winner at Purdue in 2020. Kellner credits Page for helping him transition from focusing on biology to ecology and for steering him to Purdue to continue his education.

“She was just amazing,” Kellner said. “The opportunities that she gave me as I worked for her over the four years I was at Wheaton slowly built up my skill set in fieldwork and she guided me into the idea of grad school because that was something I didn't even know was possible until I got to Wheaton. She knew I was interested in quantitative-type stuff in addition to ecology and she said ‘why don't you go talk to my former advisor at Purdue who does that kind of thing’. And so I went to interview with Rob (Swihart) and that was so great, I honestly didn't really even consider many other options at that point, because it just seemed like such a perfect fit.”

The interview with Swihart for graduate school was not Kellner’s first time on the West Lafayette campus, however, as he had come to Purdue with Page a few times as she collaborated with Dr. Gene Rhodes and others on research about raccoon roundworm.

“With Rob specifically, from my first meeting with him I could tell that he would be a very good person to work for,” Kellner said. “I had read some of his papers when I was an undergrad and they had a very heavy math aspect to them. It was just so exciting to me that you could combine the ecology and field work stuff that I was doing with Kristen with something that also had a big math component. I knew that I would have to work for someone who really was an expert on both those things, and so Rob made a ton of sense. I was also blown away when I had gone to the Purdue campus with Kristen before. That was my first experience going to a big R1 research school and it just blew me away, all the buildings and the posters up in the hallway of all the serious research that everyone was doing, and the campus was beautiful. It kind of put an impression in my mind that this is what a big, graduate research experience ought to look like. And my experience at Purdue certainly matched my expectations, to say the least.”

In his eight years at Purdue, including two as a postdoctoral researcher after earning his master’s degree (2012) and PhD (2015) in forest ecology, Kellner’s research subjects ranged from small mammals to birds to aspects of the forest ecosystem. In the beginning, he did a lot of work on the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment in southern Indiana, researching several taxonomic groups. He focused on the small mammals of the project as he worked on his master’s degree. For his PhD, Kellner focused more on the intersection of wildlife and forestry, specifically the different animal impacts on oak regeneration.

His work included topics like dispersal of acorns by small mammals, deer herbivory in clear cut openings, weevil infestation of acorns and how many acorns are being produced, looking at all of the different components of that life cycle and how animals impacted it in different ways. That resulted in Kellner building a combined model of all of those things to try to determine where wildlife was having the most impact on that process. Later he also researched the impact of the timber harvesting that happened at the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment on the bird community.

Collectively, his published research has advanced the knowledge of 100 species of Indiana wildlife (23 mammals, 69 birds, and 8 reptiles), including seven state-endangered species and five species of special concern. It is that work that made him a strong candidate for and the eventual winner of the Chase S. Osborn Early Career Award in 2021.

The Osborn Award is presented by Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources to an individual who, by writing, research, teaching or other personal accomplishments has made significant contributions to wildlife conservation in the state of Indiana.

“It’s really an incredible honor, really kind of unbelievable to me and just so humbling that my colleagues would think that highly of me to even nominate me” Kellner said. “The idea that I could pay back even a little bit of all of the time and the knowledge that my advisor and my committee and everyone else contributed to my education at Purdue, that I could turn around and contribute a little bit to knowledge of wildlife species in Indiana and specifically conservation … I'm so happy that I was able to make even a small difference in my time while I was at Purdue to sort of start paying back a little bit of the debt that I owe pretty generally, and to all of the many people at Purdue that helped me along in my career.”

From Purdue, Kellner moved on to a postdoctoral position at West Virginia University, where he continued to hone his skills and career aspirations. His past work with the Hardwood Ecosystem Experiment was part of the draw to WVU, where he would work on summing up the Missouri Ozark Forest Ecosystem project, on which the HEE was based. That and the opportunity to work with and learn from Chris Rota, who is well known in the quantitative ecology community, made it the perfect match.

“I had already worked on a bunch of different aspects of the HEE, so working on MOFEP in similar ways was a logical progression and allowed me to work on a range of vertebrate taxa,” Kellner said. “I was also able to work with Chris on some other projects that were more quantitative in nature as well.”

In 2019, Kellner accepted a position as a research scientist and biometrician at the Global Wildlife Conservation Center. The Center is part of the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) in Syracuse, the oldest institution in the United States focused on studying the environment. His work has shifted from the field to the computer lab, but he is still able to work with a variety of species.

“It's always a trade-off,” Kellner said. “I don't spend a ton of time in the field anymore, and I certainly loved that experience at Purdue and before when I did it more often, but there is something really amazing about being able to come into work and work on entirely different data sets every day. The choice I made was to focus more on the statistics and quantitative side of these problems, and work with a huge range of collaborators who can provide the expertise on the species specifics or on the ecology side. You can jump between projects much more easily if you're focused on the stats side because you don't need to be an expert, you just need to work with experts. One day, you might be working on wolves on Isle Royale and the next day you're working on vultures and the next day on lions and the next day on whales. It's really cool to be able to jump between projects like that and have an impact on a huge range of different areas, while applying more or less the same statistical tools that I’ve been using all these years. It definitely keeps it interesting and fresh.”

Kellner takes the data that is collected in the field and finds ways to clean it up, summarize it and analyze it in ways that can be translated into products like publications, figures or graphs.

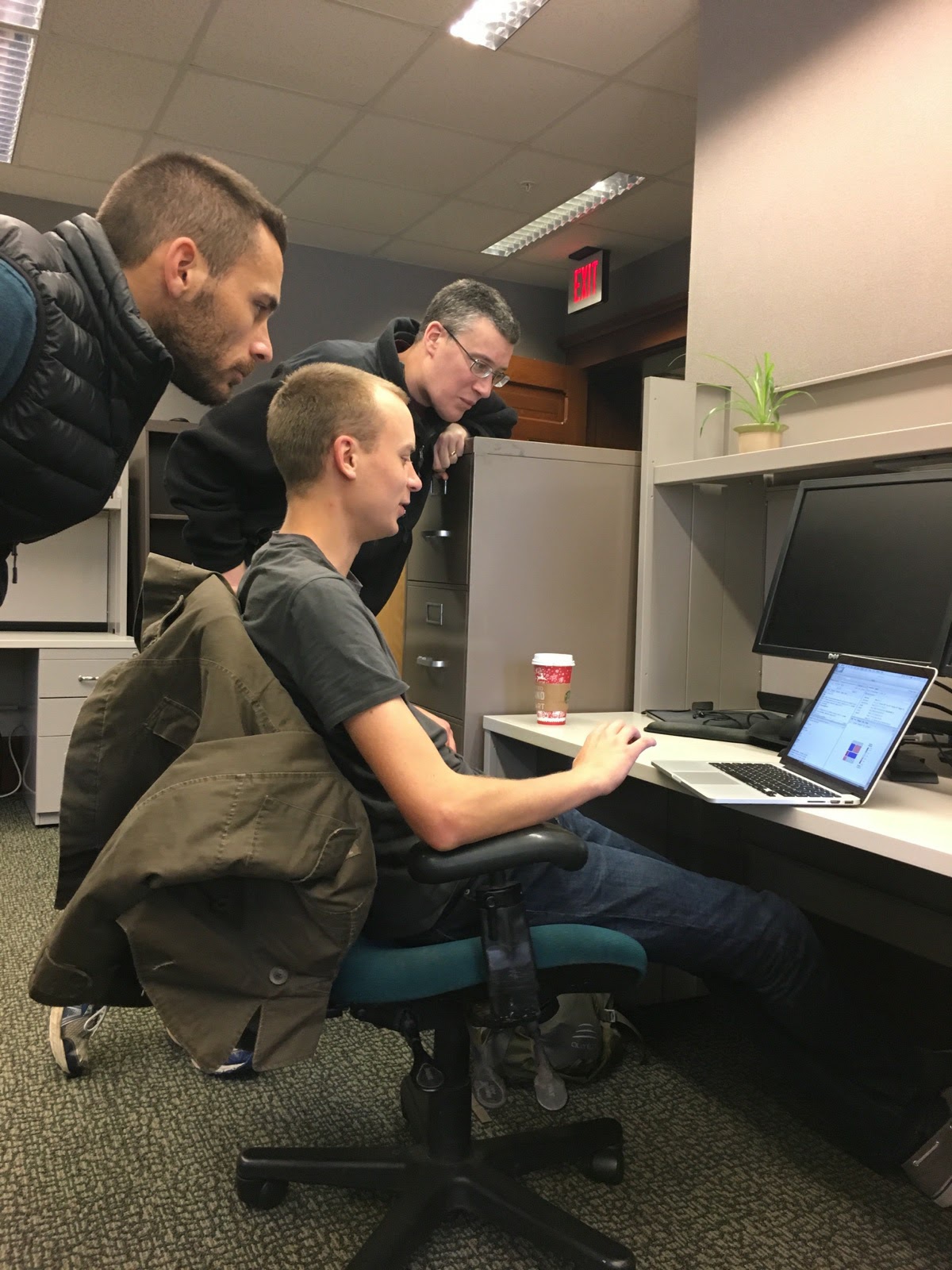

“I’m trying to take all of the messy aspects of field ecology, clean those up and solve the issues by identifying the trends and patterns that are often hidden in the data,” Kellner explains. “It’s a lot of sitting at a computer and working through data and interacting with your collaborators and figuring out their underlying goals and hypotheses and figuring out how you can design an analysis that answers the questions they had in mind when they initially designed the study. I’m primarily taking data sets and constructing models that address the hypotheses.

“I also do a lot of work on Open Source scientific software, creating tools that other people can use for their statistics. Not everybody has the monetary resources to pay a bunch of money for really expensive software so it's important to me to create something that is accessible to anyone anywhere across the world. I really like doing that because you can have a much bigger impact on the field, as potentially hundreds or thousands of people are going to use the tool that you develop. That is really exciting because a small effort you make can have a big impact overall and enable a lot of really cool studies that you otherwise wouldn’t have a chance to or time to participate in.”

Kellner’s Open Source analysis tools are freely available to help facilitate others seeking to make population density estimations for species that can’t be estimated through other means. The R package ‘jagsUI,’ which Kellner developed at Purdue in 2015 to streamline Bayesian analyses of wildlife populations and communities, has nearly 500 citations. In 2020, he published a new version of the popular R package ‘unmarked,’ which facilitates occupancy and density estimation for species in which individuals cannot be uniquely identified. Recently, he released an R package called ‘ubms,’ which uses a popular interface to fit hierarchical models in a Bayesian framework.

In total, Kellner has published 38 peer-reviewed articles, including 20 on ecology and conservation or Indiana wildlife. He also has given 27 presentations, including seven on responses of Indiana wildlife to timber harvesting and climate change.

As Kellner continues to widen the scope and impact of his work through both research and analysis tools, there is no question that his time at Purdue and the people he has met along the way provided a launching pad for his current role and whatever lies ahead in his promising future.

“It was a perfect match for my career goals to end up at Purdue; it was exactly what I needed,” Kellner said. “Having a fantastic advisor was amazing and my graduate student colleagues were all amazing. The resources were incredible, like really nothing I've seen anywhere else I've been in terms of the resources that were available to me as a graduate student. I'm so happy that I chose to go there. In some ways I stumbled into it because I had this connection from Wheaton and it just ended up being lucky that I went there. It really has laid the foundation for everything I've been able to do since then. I'm incredibly grateful to everyone at Purdue for believing in me and providing me with the research resources I needed to be successful both at Purdue and afterward. I hope to continue to contribute in the future, whether that’s through open source software or directly through collaboration with people at Purdue, to continue adding that body of knowledge.”

In the video below Kellner credits some of the many individuals who impacted his career and led him to where he stands today, as Purdue FNR’s 2021 Early Career honoree for the Chase S. Osborn Award in Wildlife Conservation.