Trade and trade policy outlook, 2024

January 16, 2024

PAER-2024-02

Russell Hillberry, Professor of Agricultural Economics

In last year’s outlook (Hillberry, 2023), the implications of the Russia/Ukraine war for international trade in agriculture were a major focus. Nearly-comprehensive sanctions on Russia and Belarus, as well as war-generated disruptions in Ukraine and Russia’s exports of agricultural commodities, had disrupted many markets relevant to U.S. export-oriented agriculture. While both the war and the sanctions remain, their economic consequences for agriculture seem to have been mitigated in the last year.

Fertilizer prices were one of the markets most disrupted by the war. Russia and Belarus are major suppliers of fertilizers, especially potash. Reduced supplies of natural gas to Europe also disrupted the production of other fertilizers there. Fertilizers prices fell through-out 2023 (Quinn, 2023). It seems that fertilizer markets have largely adjusted to the shock, through increased output of alternative suppliers, and the rearranging of international supply chains in this input (Lvovskiy, 2023).

Prior to the war, Ukraine and Russia were both large exporters of agricultural commodities, especially wheat. Wheat prices fell throughout 2023, and now sit below their prewar levels (USDA, 2023). Supply chains in wheat markets have also been spatially reallocated, with Ukrainian wheat often now travelling through Europe rather than the Black Sea. Associated disruptions to the European market generated some trade policy disputes in 2023, including the filing of a World Trade Organization (WTO) complaint by Ukraine against protective measures taken by Poland, Hungary and the Slovak Republic (WTO, 2023).

Oil and gas markets were also disrupted by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Prices in these markets also appear to have normalized. The retail price of diesel in the U.S. for example, sits very near its pre-war levels, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Retail Price of Diesel Fuel (on Highway), in Dollars per Gallon.

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED database

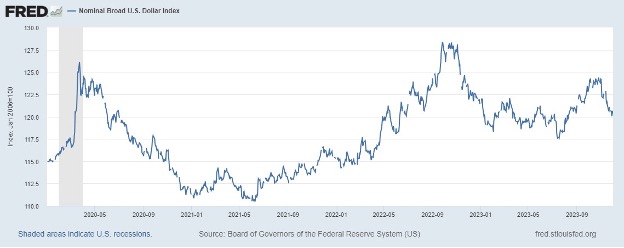

Last year’s review noted that the rapid increase in US interest rates associated with an inflationary spike had led the U.S. dollar to appreciate against other world currencies. Other things equal, an appreciating dollar should reduce the costs of foreign inputs, but make US exports less competitive on foreign markets. Last year at this time, this author conjectured that subsiding inflation would lead to U.S. interest rate cuts, which might have been expected to lead to a dollar depreciation, reversing earlier moves. While inflation has subsided, the Federal Reserve has yet to begin cutting interest rates. It seems likely that this will happen in 2024, though the scale of such cuts is difficult to forecast (Moore 2024). If the cuts are sizable – which would be more likely if the economy were to slow – they would probably lead to dollar depreciation. 2023 saw the value of the dollar fluctuate, but finished the year at basically unchanged from the same time last year.

The most significant trade policy developments of 2023 were not directly related to agriculture. Under President Biden, the U.S. has offered large federal subsidies to manufacturers (and prospective manufacturers) of semiconductors and electric vehicles. Purchasers of electric vehicles also qualify for federal subsidies. All of these subsidies come with strings attached, namely requirements to use U.S. domestic content, or in some cases the content of preferred U.S. trading partners.

While the subsidies have their purposes, from a trade policy perspective they pose important problems. First, they appear to be inconsistent with the U.S. WTO commitments, and they have angered long-time U.S. trading partners (Rappeport, 2023). Second, subsidies of this size have consequences similar to tariffs; they push U.S. economic activity away from sectors where the U.S. has comparative advantage (including agriculture) and towards sectors that may not be cost competitive absent the subsidy. Third, the subsidies must also be financed, generating an eventual tax liability on other sectors of the economy. As with tariffs, U.S. subsidies have also generated responses by foreign policymakers, which undermine some of the benefits that U.S. subsidies might have otherwise generated (Swanson et al., 2023).

What are the implications for export-oriented agriculture? There are several. First, trade policy makers in foreign governments who are frustrated by US trade policies in other dimensions are unlikely to look favorably on U.S. requests for improved market access in agriculture. Second, the focus of U.S. trade policymakers has clearly shifted away from pursuing the interests of export-oriented agriculture; improving market access for agriculture has been a secondary consideration, at best. Finally, resource allocation costs associated with policies aimed to support favored manufacturing sectors are relevant. Policy-induced expansion of one sector of the economy implies reduced activity in the others.

Although the bright spots in this environment are few, a 2023 WTO agreement limiting fishing subsidies suggests that, despite setbacks in the last decade, the multilateral body can still play an important role in international economic relations. In the agreement, countries agreed to limit their subsidization of commercial fishermen in ocean waters. If it is successful in reducing overfishing, the agreement should benefit aquaculture, at least in the short run. More broadly, its implications for agriculture are that the WTO is still a potentially effective venue for negotiating reductions in subsidies around the globe. Further global progress on reduced subsidies in agriculture would be useful for those U.S. producers who are able to compete on international markets without them.

Trade Policy and the 2024 U.S. Presidential election

The 2024 event that is most likely to affect trade policy is the 2024 Presidential election. While voting in the primaries has not yet begun, it seems likely that the candidates chosen by their prospective parties will be President Joe Biden and Former President Donald Trump, a rematch of the 2020 campaign. When election season rolls around, most national candidates bow to pressure to protect uncompetitive industries that are important in politically sensitive states. These two candidates have proven histories that make them more likely than most recent candidates to do so. Those involved in export-oriented agriculture should certainly be paying attention, since those actions typically undermine their the interests of export oriented agriculture.

For what follows we take as given the proposition that the US trade policy orientation that best suits the interests of export-oriented agriculture are conditions similar to those that existed in 2000, with most of those conditions still in place as late as 2016. This means that U.S. trade policy is largely stable and predictable, with low tariffs and broad adherence to the rules-based global trading system that has done so much since World War II to advance global peace and prosperity, while at the same time enabling U.S. farmers to increase their exports around the world. Good-faith negotiation of preferential trade agreements with countries that offer sizable prospects for growth in agricultural exports are probably good for the agricultural sector, even if not ideal for the economy as a whole.

Former President Trump’s trade policy was almost entirely antithetical to these ideals. His first act as President was to withdraw from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a preferential trade agreement including most of large economies in the Asia-Pacific (ex-China). U.S. producers lost the improved market access commitments made in the agreement by large prospective agricultural markets such as Japan and Korea. Agricultural producers in countries that remained in the agreement (Australia, Canada and New Zealand, among others) instead benefited from the new commitments, many of which the U.S> had helped to negotiate. Trump then moved on to starting a trade war with China, generating retaliatory tariffs by China on U.S. soybeans and other products. Next Trump broadened his trade war, raising tariffs on long-standing US allies and trading partners like Japan and the European Union. While the retaliatory tariffs from Europe and other trade partners were less obviously consequential for large commercial agriculture than were China’s tariffs, they reduced U.S. agricultural exports nonetheless (Morgan, 2022). Trump next set out to undermine the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement mechanism, refusing to allow any appointments to the appellate panel that is necessary for penalties against countries that violate trade rules (Packard, 2020). In his efforts to renegotiate NAFTA, his impulse to tear up the agreement altogether had to be restrained by agricultural interests in Washington (Baxter, 2017). While the fallout from his policies for agricultural producers finally began to register with him near the end of his administration, his efforts to undo the consequences of his own policies were limited in their effectiveness (Bown, 2022).

One might have hoped that President Biden would return U.S. trade policy to its pre-2017 settings. Early moves to normalize trade relations with longstanding allies like Europe and Japan were important steps in this regard, but much of the rest of Trump’s trade policy was left in place. As a result, many of the countermeasures that other countries took in response to Trump’s tariffs are also still in place. Despite recovering somewhat from the depths observed during the trade war, the U.S. share of China’s agricultural imports has plateaued below its prior levels (Bown and Wang, 2023). While the Biden administration has touted its efforts to revive the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism (Bade, 2023), critics argue that the rhetoric rings hollow (Bacchus, 2023). Biden’s expansion of “Buy American” policies, together with his green subsidies and associated trade restrictions also seem inconsistent with current WTO rules (Kaufman et al., 2023). Agricultural interests in Washington are pushing the Biden Administration to try to negotiate improved market access through the WTO, though this is clearly not a centerpiece of his agenda (Palmer, 2023),

It will be interesting to see the degree to which trade policy becomes an issue in the 2024 campaign. President Biden rarely speaks about this issue directly, though his approach to the issue has begun to come into focus, and it seems reasonable to expect him to continue on the path he has already taken. President Trump seems primed to raise the prominence of trade policy again, recently proposing 10 percent tariffs on virtually all imports to the United States (Stein, 2023). Should Trump be elected once again, one might expect consequences for U.S. agriculture that are similar to those that occurred in his previous term.

In the post World War II period, U.S. Presidents of both parties traditionally supported the expansion of global trade through negotiation with U.S. trading partners. A key U.S. goal of these negotiations has often been to increase market access for U.S. agricultural producers. It is thus surprising that in 2024 we should see once again the match-up that nearly everyone expects. On the one hand we have a sitting president who seems indifferent to the market access goals of U.S. agriculture. On the other hand we have a former President, unchastened by the fallout of the trade policies of his first term, promising more of the same if he is returned to office. Perhaps the more relevant question is this: why have the interest groups and politicians who represent rural midwestern voters been so far so unsuccessful in raising the salience of trade policy in the Republican Presidential primary campaign?

References

Bade, Gavin (2023), “Biden officials try to revive a key world trade referee after Trump steamrolled it,” Politico, https://www.politico.com/news/2023/09/22/tai-targets-china-climate-in-call-to-reform-wto-00117491

Baxter, Annie (2017), “The agriculture industry urges caution on the NAFTA renegotiation,” Marketplace, National Public Radio, July 17, https://www.marketplace.org/2017/07/17/agriculture-sectors-urges-caution-nafta-renegotiation/

Bacchus, James (2023), “Biden Administration Continues to be Wrong about WTO,” Cato at Liberty weblog, September 26, https://www.cato.org/blog/biden-administration-continues-be-wrong-about-wto.

Bown, Chad (2022), “China bought none of the extra $200 billion of US exports in Trump’s trade deal,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, July 19. https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/china-bought-none-extra-200-billion-us-exports-trumps-trade-deal

Bown, Chad and Yilin Wang (2023) “China is becoming less dependent on American farmers, but US export dependence on China remains high” Peterson Institute for International Economics, March 21. https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/china-becoming-less-dependent-american-farmers-us-export-dependence-china

Hillberry, Russell (2023) “Trade and Trade Policy Outlook 2023” Purdue Agricultural Economics Report. https://ag.purdue.edu/commercialag/home/paer-article/trade-and-trade-policy-outlook-2023/

Kaufman, Noah, Chris Bataille, Gautam Jain, and Sagatom Saha (2023) “The US broke global trade rules to try to fix climate change – to finish the job, it has to fix the trade system,” The Conversation, September 5, https://theconversation.com/the-us-broke-global-trade-rules-to-try-to-fix-climate-change-to-finish-the-job-it-has-to-fix-the-trade-system-212750

Lvovskiy, Lev (2023) “Belarus’ potash industry is going through the mill” https://www.ips-journal.eu/topics/economy-and-ecology/belarus-potash-industry-is-going-through-the-mill-7139/

Morgan, Stephen (2022), “Retaliatory Tariffs Reduced U.S. States’ Exports of Agricultural Commodities” Amber Waves, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, March 7. https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2022/march/retaliatory-tariffs-reduced-u-s-states-exports-of-agricultural-commodities/

Moore, Simon (2023) “Markets See Spring 2024 Interest Rate Cuts, But The Fed Isn’t There Yet,” Forbes Magazine, Dec 5. https://www.forbes.com/sites/simonmoore/2023/12/05/markets-see-spring-2024-interest-rate-cuts-but-the-fed-isnt-there-yet/?sh=3a5a3a2020fc

Packard, Clark (2020), “Trump’s Real Trade War Is Being Waged on the WTO,” Foreign Policy, January 9. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/01/09/trumps-real-trade-war-is-being-waged-on-the-wto/

Palmer, Doug (2023), “Farm groups press Biden administration to make WTO market access proposal.” PoliticoPro, November 8. https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2023/11/farm-groups-press-biden-administration-to-make-wto-market-access-proposal-00126104

Quinn, Russ (2023) “DTN Retail Fertilizer Trends: Retail Fertilizer Prices Evenly Mixed at End of November,” Progressive Farmer, December 6. https://www.dtnpf.com/agriculture/web/ag/crops/article/2023/12/06/retail-fertilizer-prices-evenly-end

Rappeport, Alan (2023) “U.S. Looks to Allay European Fears of a Subsidy War” New York Times, October 31. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/31/us/politics/us-europe-subsidies.html

Stein, Andrew (2023) “Trump vows massive new tariffs if elected, risking global economic war,” The Washington Post. August 22. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/08/22/trump-trade-tariffs/

Swanson, Ana, Jeanna Smialek, Alan Rappeport and Eshe Nelson (2023), “U.S. Spending on Clean Energy and Tech Spurs Allies to Compete” New York Times, December 8. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/07/business/economy/clean-energy-us-europe.html

U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), (2023), “Prices Received: Wheat Prices Received by Month, US.” December, https://www.nass.usda.gov/Charts_and_Maps/Agricultural_Prices/pricewh.php

World Trade Organization (WTO), (2023) “Ukraine initiates WTO dispute complaints against Hungary, Poland and Slovak Republic” September 21, https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news23_e/ds619_620_621rfc_21sep23_e.htm