January 14, 2013

Farm Growth: Venture Analysis and Business Models

Continued consolidation and concentration in the agricultural industries has stimulated numerous discussions and debates about the advantages and disadvantages of large vs. small firms and why the general trend/direction of most structural change in agriculture is to larger scale businesses. Why in general do the big get bigger, and how likely is it that this phenomena of growth will continue or dissipate? What is the economic and financial underpinning for growth of a business, and why is consolidation and concentration a natural result of business success? Given the numerous new venture growth options available, how does one make a reasoned choice? And what alternative business models might be used to organize and implement the growth process?

The Logic of Growth

Much of the discussion of size and growth by economists and financial analysts focuses on economies of size and managerial incentives and motivations. There is ample evidence that the cost curve for most firms in most industries is downward sloping – larger businesses generally have lower costs of production/distribution than smaller businesses. And in general, many managers are motivated to expand and grow their business: a growing business provides more opportunity to employ the skill sets of an increasingly capable management team; the capital markets and investors generally reward growing firms with better stock prices; managerial compensation and rewards frequently include a sales growth incentive; suppliers often provide better pricing and other incentives to firms that are expanding their business and increasing their purchases; and buyers of products often prefer to do business with fewer firms and so will provide preferred supplier incentives including better pricing or guaranteed purchases to businesses with larger and growing volumes.

Certainly size economies and managerial motivations are critical and provide strong explanations for growth – for why the big get bigger. But is there more to the story – are there additional reasons and/or explanations for growth, particularly for those businesses that are currently successful but only modest size. Is in fact growth a natural phenomenon – a result rather than a goal? And why might firms grow and industries continue to consolidate even if size economies do not exist and/or managers and the stakeholders of the business are not motivated to grow? What is the logic of growth? And why is consolidation and concentration a “natural” phenomena?

Economies of Size

The argument that growth is a natural phenomenon of success in managing a business starts with the concept of economies of size. Few debate the fundamental shape of the cost curve – smaller firms generally have higher per unit cost of production/distribution than larger firms. The real issue however is not whether costs per unit of output decline as output increases, but whether at some size or scale, do costs per unit begin to rise. The key question is whether the classic academic U shaped cost curve characterizes agricultural businesses, or whether the cost per unit of output remains relatively constant as size increases after the initial decline from smaller scale to minimum efficient size firms and plants. The detailed empirical evidence is available elsewhere, but in essence, studies of the cost structure for agricultural businesses as well as most other industries indicate that the cost curve driven by production and technical efficiency is relatively flat after the minimum efficient size is achieved, and that successful managers are generally available over time to continue to constrain any cost per unit increases as the firm expands or grows.

One of the fundamental reasons why costs continue to decline as output increases is because of the experience curve. The basic premise of the experience curve is that as a firm accumulates more knowledge and expertise over time, the work force learns how to become more efficient and effective, and consequently productivity (output per unit of input) increases – thus resulting in lower cost per unit of output. Studies in a number of industries suggest that the cost reductions associated with the experience curve can be as much as 20% with each doubling of accumulated output. Consequently, as a firm grows over time efficiency increases and costs decline even after all economies of size have been exploited because of the cost reductions associated with the experience or learning curve.

Augmenting the technical efficiency/productivity benefits of size economies and the experience curve are the advantages a growing larger scale business has in its supplier and buyer relationships compared to a smaller scale business. Economists call these phenomena pecuniary economies of size. Larger businesses can typically negotiate better prices or more attractive terms from input suppliers, and thus have better and lower cost access to production inputs including capital and other raw materials. They also typically have more advantageous access to product markets and thus can obtain higher prices and better terms for the output they produce. The classic economic arguments therefore are that larger scale and growing businesses generally have lower costs, higher prices and better operating profit margins than smaller scale operations.

Investable Funds

But this is not the end of the story. The larger operating profit margins per unit of output for larger size businesses when combined with the higher output results in more total income and profit for larger compared to smaller businesses as one would expect. The use of this income is equally if not more important in understanding the growth of successful businesses than the efficiency/productivity arguments presented thus far. Particularly for small and modest size family owned businesses, the salaries/withdrawals/payouts to the business owners/managers typically account for a higher percentage of the firm’s annual earnings compared to larger scale/size businesses. In essence, larger businesses have lower “payout” percentages, and this lower cash drain on earnings combined with the typically higher earnings results in substantially more retained earnings for larger scale businesses compared to those of smaller size/scale. A larger absolute amount of retained earnings means that larger scale businesses can acquire more resources and increase their output more rapidly than a smaller scale business that may need to use most of its earnings to support the withdrawals or payouts to the entrepreneur and management team. Even if the larger scale operation does not have any higher profit margins per unit of output, if the size of the business is sufficient that the payout percentage is lower than that of the small business, the larger business has more potential to grow faster because of the more rapid accumulation of retained earnings. In this context, growth is a “natural” result of business success, and larger businesses have more “natural” growth potential because of their typically higher savings or retention rate compared to smaller businesses. In essence, larger scale businesses have a higher sustainable growth rate, resulting in the big getting bigger.

Debt Financing and Risk Management

We have yet to introduce issues of debt financing and risk management into the discussion. The key questions are whether small or large firms have a relative comparative advantage in either accessing debt or managing risk that would mitigate the efficiency and financial advantages of larger scale units discussed thus far. As to debt utilization, firms that accumulate retained earnings more rapidly are typically better positioned to obtain more debt as well (strictly in absolute terms) — a larger portion of the business earnings are available to service that debt. So larger scale businesses typically have both more debt and equity resources available to expand operations compared to smaller scale businesses, and thus have a faster rate of growth.

As to risk management, larger scale businesses typically have the resources to acquire the capabilities and the instruments to manage operating risk at a lower cost per unit of output compared to their smaller scale counterparts. More effective management of operating risk enables those firms to safely use more debt in both absolute and relative terms compared to smaller scale businesses. The combination of more income available for debt servicing combined with a more predictable/less variable operating income because of better risk management means that larger scale units can be more highly leveraged. This additional access to credit augments further the ability of the larger scale operations to acquire more resources, produce more output and grow at a faster pace compared to smaller scale businesses.

Venture Options: How Do You Choose?

Successful farmers today have numerous business venture opportunities from which they can choose. The options range from business reinvestment including upgrading and modernizing their current machinery equipment line or livestock facilities, acquiring new farmland or other capital assets, purchasing distressed assets of those producers who have not been as successful as they have been, or deleveraging (paying down debt) the business. Alternatively, some producers are considering non-farm investment alternatives including agricultural related businesses, commercial real estate, stocks and mutual funds or bonds as a strategy to diversify their investment portfolio. And in some cases maintaining a liquid position including significant amounts of cash to take advantage of future opportunities may be the best strategy. The key question is how do you choose which investment option or new business venture to pursue? There are eight criteria that should be used in making investment or new venture choices.

Strategic Fit

The first criteria is that of strategic fit. Strategic fit refers to whether the new venture leverages the resource base of the business and is consistent with the strategic direction or focus of the current business. If the new venture requires a set of skills that are currently not part of the resource base of the business, it has much less potential for success. For example, a new venture that can only be successful if one maintains intense relationships with the customer may not fit well with a management team that is intensely focused on operational efficiency and cost control as is typical in a commodity oriented business. Some characterize strategic fit as what a business focuses on in terms of its passion—what really excites and motivates not only the owners, but the management team.

Expected Returns

A second criteria that should be considered in choosing an investment or new business ventures is the expected returns from the venture. Undoubtedly, the current earnings or income are a major determination of the attractiveness of a new business venture. But there is more to the story than current income. The potential growth in earnings or income should also be considered – for some ventures the earnings in the early years may be only modest, or there may in fact even be a loss as often characterizes new start-up ventures, but the growth in earnings after the start-up phase and in subsequent years of the life of the venture is substantial. This earnings growth potential may significantly offset the modest current earnings from the investment. Furthermore, synergies between the current enterprises in a business and the new venture should be taken into account as the new venture might increase the efficiency of use of current resources and/or generate cost savings from eliminating redundant resources. And tax considerations must be taken into account – even if a venture incurs losses in the early years, these losses may be able to be used to offset income elsewhere in the business and thus create tax benefits.

Risk

A third criteria that should be considered is the risk of the venture and the risk that venture contributes to the overall business. Venture risk has two critical dimensions– the variability in the earnings stream generated by the venture, and the variability or uncertainty associated with the value that the venture creates for the business. Most of the discussion of risk in the agricultural sector focuses on earnings or income variability, but the potential uncertainty in the value created as reflected by the valuation of the new venture on the firm’s balance sheet should receive equal emphasis, particularly when acquiring new startup ventures, or purchasing capital assets such as land that have exhibited both value increases as well as decreases. It is critical to make sure that one does not over-bid for capital assets, because subsequent declines in the value of those assets will result in a decline in the overall value of the business. Whether or not the new venture increases the overall risk of the entire firm or reduces that risk should also be given consideration. The complexity of the diversification vs. specialization criteria in making decisions about new venture expansions merits detailed analysis as will be discussed later.

Funding

The fourth criteria that should be considered in any new business venture decision is that of the capital required to implement the acquisition. The sources of funding for the venture – debt vs. equity – are an important consideration both in terms availability and cost, as well as what impact this funding might have on the overall leverage and financial risk of the business. But it is not just the funding needed to acquire the capital assets of the new venture – the working capital funding should also be evaluated but is often ignored. In fact, for many new ventures, the significantly increased working capital requirements to fund the venture through the startup phase may be the biggest challenge – lenders frequently find that they encounter more serious problems in funding the dramatic increases in working capital for many new ventures then they do the capital assets which often can be more accurately predicted and anticipated in volume of funds needed as well as more solidly collateralized.

Entry/Exit

A fifth criteria important in choosing a new venture is the cost and ease of entry and exit. Clearly, if a new business venture requires a purchase premium, the cost of entry may be excessive. As noted earlier, one should be careful about over-bidding for assets in the start-up or expansion process. But the ease of exit should also be given consideration when entering a new venture. The flexibility of selling the business or dropping the venture if it does not perform as expected or does not fit as was anticipated in the overall strategy of the business should be considered. And the implications of the new venture or business succession and continuity should also be part of the analysis – can the business for venture be easily “spun off” if an exit decision is made or will significant cost and challenges be encountered in exiting the venture. In essence, the flexibility the new venture exhibits in terms of exit and the liquidity in terms of ease of exit should be considered at the point of entry or start-up since this possibility always exists.

Value Creation

A sixth consideration in choosing a new venture is whether or not it will create value for the entire business. As we have noted earlier, the potential gain or loss in the value of the assets is an important consideration in initiating a new venture. Additional dimensions of this value creation process include whether or not the new venture has the potential to be an inflation hedge – will the value of the business increase in inflation adjusted real terms as well as nominal terms. And what kind of intangible value does the venture create beyond the “hard” asset value of the capital assets? Does the new venture create “option value” – a value associated with protecting a position or creating opportunities that may not be possible without the assets or the new venture? And what is the terminal or residual value of the asset or venture if it would be sold or liquidated? In many cases, the prime objective of initiating a new venture may not be the current earnings and income generated on an annual basis, but its residual or terminal value. In fact, this is the major goal of venture capitalists who invest in new projects – to create value that can be captured at the subsequent sale of the venture. Although this may not be the prime goal of a farmer who is growing to expand his business, it should not be ignored – value creation and capture may be as or more important for some ventures than generating current earnings and income.

Managerial Requirements

A seventh consideration in choosing new ventures is the managerial complexity and requirements of that venture. In many cases the new venture may use the managerial skill set of the current business, but a realistic assessment of current management skills and those skills required by the new venture is essential in selecting a venture. Will adding the new venture increase the management requirements beyond the current managerial capacity of the business? Are additional managerial skills needed to be successful in operating the new business venture? Can time be allocated by the current management team to “get up to speed” in the new venture? Will the acquisition increase the complexity of the current business, or will it reduce operating constraints and improve as well as simplify the managerial decision processes? Will managerial capacity expanded with the new venture, or will managerial resources need to be diverted from the current business to the new venture, thus putting increased pressure on the current management team? Will the business or venture have a relatively independent and separate management structure, or will it be integrated from both a managerial and operational perspective with the current business? In many cases, the most significant challenge in new venture expansions is that of the managerial requirements to be successful in that venture, and getting the managerial resources in place to achieve that success.

Portfolio Fit

The final consideration in any new venture expansion decision is how does that venture fit in the portfolio of current business activities? Does the new venture increase the risk of the overall business because its income stream is positively correlated with the income stream from the current enterprises in the business, or does the venture reduce the risk of the business because the income streams are negatively correlated? Does the venture increase the firm’s concentration in a particular stage of the value chain which might increase its market presence and market share and thus improve its bargaining position as a key account for suppliers or preferred provider/supplier for buyers? Or does the venture move the business into additional stages of the value chain and thus increase the opportunity to capture value in up-stream or down-stream activities? Does the venture allow the current management team to “experiment” in a set of new activities and enterprises without taking excessive financial risk – again an options approach to new venture expansion and growth? How the new venture fits in the overall business portfolio is an important consideration in any expansion decision.

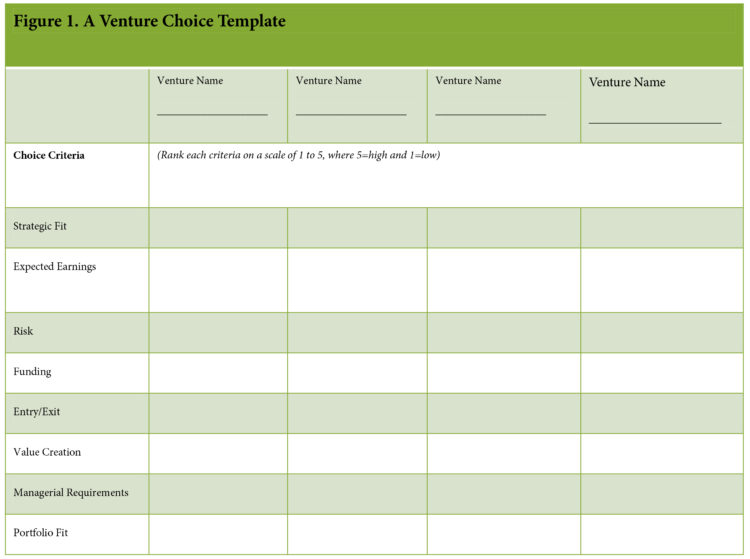

Figure 1 provides a scorecarding tool to use in implementing the assessment of new ventures using this set of criteria. Each venture that is being considered is evaluated on a scale of 1(low) to 5(high) on each of the criteria. Adding these rankings for the eight criteria provides some insight into which ventures might have the highest overall score and thus be the most preferred expansion option. But more importantly, the relative rankings on each of the criteria should be carefully evaluated since different criteria suggested here might be the most important in choosing a particular business venture. The key value created by this scorecard is the systematic evaluation of the various options on the various criteria, not the overall score obtained for the venture.

Alternative Business Models

Organizing and implementing the growth/expansion process is an important decision that includes alternatives well beyond the traditional organic growth strategy used by most farmers in the past. Eight different business models will be discussed here.

Organic or Internal Growth

This is the traditional approach to expansion where assets are acquired and added to the current business. Such expansions might include purchasing or renting additional land, livestock facilities or machinery and equipment and operating it as part of the current business. In some cases this approach might include a “greenfield” start-up, but more typically it is an incremental expansion of the current operation. If the expansion is sufficiently large or geographically separated from the current farming operation, it may be operated as a relatively independent entity from a production perspective using the increasingly common “replicate” strategy of the industrial sector where an optimal plant size is determined and expansion occurs by building a new plant. This replicate strategy is commonly used in the livestock sector where for example a 3000 cow dairy is considered to be a minimum efficient scale dairy operation and expansion occurs by replicating this 3000 cow facility at a different site. A “hub and spoke” model might be used if some of the physical resources such as feed processing are more efficient when centralized, whereas other resources such as swine production barns are best to be geographically dispersed.

Merger/Acquisition

The merger/acquisition expansion strategy is commonly used in the business world and is becoming increasingly popular in production agriculture. This approach involves the acquisition of a business rather than the individual or selected assets of that business. If the target acquisition includes leased as well as owned resources such as land, the capital requirements to control the resources may be significantly reduced (assuming the leases are assignable). In some cases this approach facilitates the exit or retirement of the owner/operator of the acquired business – the “exiting/retiring” farmer might be retained on a part or full time basis to carry-out various production activities such as tillage operations, grain hauling or livestock feeding. Clearly a challenge of this strategy if the acquisition includes personnel as well as physical and financial resources is the potential redundancies that may exist with some of the acquiring business’s current management and operations personnel, as well as the potential of different corporate cultures in the current and the acquired businesses.

The Franchise

A third business model that is being experimented with in some farming regions might be described as the franchise model. The concept of this approach is that much like a franchise structure in other industries, the franchisor offers to the franchisee a set of services and protocols including market access, standard operating procedures (SOP’s), input discounts, qualified supplier status, managerial oversight, etc. The franchisee is in essence acquiring the “rights to operate” in a particular geography using the services and protocols of the franchisor. Because of the size and scale of his business, the franchisor is expected to be able to obtain cost reductions or better prices from suppliers and buyers and is also expected to accelerate the learning process of franchisees through benchmarking of best management practices of the most successful franchisees. The critical issues to be considered in using this business model are whether or not the franchisor is providing value in the services and protocols offered to justify the franchise fee.

Partnership/Joint Venture/Strategic Alliance

The partnership/joint venture/strategic alliance is a common business model used to combine the resources of two or more businesses to obtain size economies, increase market access, facilitate business succession or intergenerational transfers, etc. The business arrangement might include the entire business, or only specific business activities (and thus assets) such as machinery sharing, or a new upstream or downstream business. The challenge of such business arrangements is the joint decision making typically required and the conflicts (or indecision) that may result. An additional challenge is that it is often difficult to exit such business arrangements or to exit the venture, so it is best to agree during the formation process on the termination/liquidation/buyout arrangements.

The Service Provider

A service provider business model is commonly used in both grain and livestock production in the form of custom harvesting/chemical application/farming activities and contract raising of livestock, respectively. The basic concept is that resources are provided or activities performed by one party for another for a fee. The service provider is an independent contractor rather than an employee. Rental of farmland, contracting of the labor or workforce from a labor contractor, or acquiring marketing, legal or management services from a professional service firm are additional examples of this business model and are commonly used in the agricultural sector.

Asset/Service Outsources

Complementing the service provider business model (and in many cases the counterparty to the arrangement) is the asset/service outsourcer. Leasing and rental arrangements are increasingly common in the farming sector to obtain machinery and equipment services as well as the land resource. This business model often reduces the capital outlay needed to obtain control of these resources, and also increases the flexibility to expand or downsize the business more rapidly in response to changes in the business climate. Outsourcing professional services such as accounting, marketing, veterinary and health care, etc. is common in agriculture as noted earlier.

The Agricultural Entrepreneur

Although the “agricultural entrepreneur” may not be a unique business model, it is a unique and increasingly common approach to business in the agricultural sector. More farmers are investigating the business opportunities they might pursue in the supply industries such as machinery/equipment or seed and chemical/crop protection retailing as well as providing trucking and logistics services. Others are evaluating first handler businesses such as grain origination and storage, and even product processing in the ethanol, pork and dairy industries. Land clearing, construction, tiling and similar business ventures are being considered to more fully use specialized assets. And some farmers are involved in non-farm ventures in rural communities including rental housing, banking and manufacturing businesses as a form of diversification as well as more fully using unique managerial skills.

The Investor

The investor business model is characterized by the how and why an agricultural entrepreneur acquires or invests in a business. In this situation, the acquisition is motivated primarily by financial objectives with the expectation that the business will require little managerial input or oversight. This might be characterized as the Warren Buffet approach to business investments – buy businesses (not assets) that have good management in place, are in strong competitive positions in their market place and are well buffered from competition, and are currently undervalued in the market. The strong current management is kept in place and the business is treated largely as a passive investment with broader access to capital and other resources but little management input from the investor.

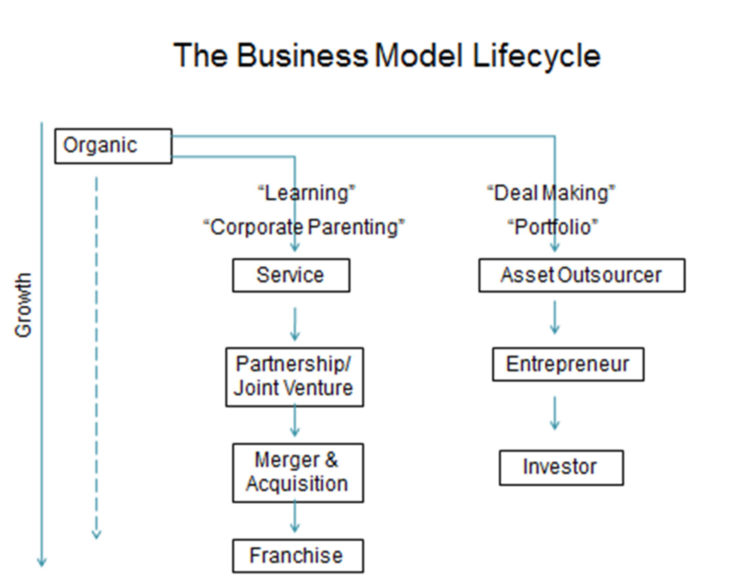

Finally, the business models we have identified might follow a logical progression or lifecycle over time as described in Figure 2. One approach to growth/expansion is to use a corporate parenting or learning approach where the focus is to improve the performance of the businesses over time by leveraging experience and learning across the businesses. The business models used to implement this strategy would be the service provider, partnership/strategic alliance/joint venture, franchising and merger and acquisitions. An alternative approach is that of deal making with the objective of obtaining a well performing portfolio of business ventures. The business models used to implement this strategy would be the asset outsourcer, the entrepreneur and the investor. The organic business model is relatively independent of the other business model approaches to growth and expansion.

TAGS:

TEAM LINKS:

RELATED RESOURCES

Margaret Lippsmeyer, Michael Langemeier, James Mintert, and Nathan Thompson segment U.S. farms by farm resilience, management practices, and producer sentiment. This paper was presented at the Southern Agricultural Economics Meeting in Atlanta, Georgia in February.

READ MOREUPCOMING EVENTS

We are taking a short break, but please plan to join us at one of our future programs that is a little farther in the future.