Microbubble findings could reduce chemical, water use in food processing

Cleaning and sanitizing food processing equipment requires using chemicals and copious amounts of water for rinsing those chemicals away. It’s possible – if it can be done correctly – that creating microscopic bubbles in water could reduce or eliminate the need for those chemicals.

A Purdue University study may hold the key to accurately and consistently producing microbubbles that could be used for cleaning, as well as foams used in foods, rapid DNA and protein assessments, destroying dangerous bacteria and more. In the journal Scientific Reports, Carlos Corvalan, an associate professor of food science, and Jiakai Lu, a former postdoctoral researcher in Corvalan’s lab, describe the speeds at which pores made in films close, which is comparable to similar processes when bubbles are formed.

“When injecting air from a needle into a bubble, the bubble neck keeps thinning and the bubble forms,” said Lu, who is now an assistant professor of food science at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “Understanding the collapse of a pore is going to help us understand the pinch-off point of bubble generation.”

When a pore or hole is formed in a fluid, it has two options and will trend toward the one that uses the least amount of energy. If the hole is large, it continues to expand. Smaller holes collapse, closing themselves up.

Understanding the speed at which those pores close has been elusive because, as a hole collapses, its curvature becomes infinite and a singularity is formed.

“This touches on a deep problem in physics,” Corvalan said. “When that singularity is formed, the equations that govern the process don’t work any longer. We found ways to go around this problem to predict when the hole is going to collapse and use that to predict the volume of the microbubbles and the time it will take to form them.”

In viscous fluids, pores close at a constant rate. But in water, as a pore closes, the speed at which it closes continues to accelerate. For fluids with intermediate viscosity, the pore begins closing at an ever-increasing rate, but at a certain point that rate becomes constant until the pore closes.

Using high-fidelity computational models, Corvalan and Lu predicted the point at which the speed changes from ever-increasing to constant. Using that information, Corvalan and Lu can inform the design of pumps that will create the right size of bubbles.

“Although we have a singularity, the speed for the collapse becomes essentially constant,” Corvalan said. “If we want to control the volume of microbubbles, we would have to determine when the neck of the bubble would collapse. Now we are able to predict when it will collapse, and we can control their formation.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture supported this research.

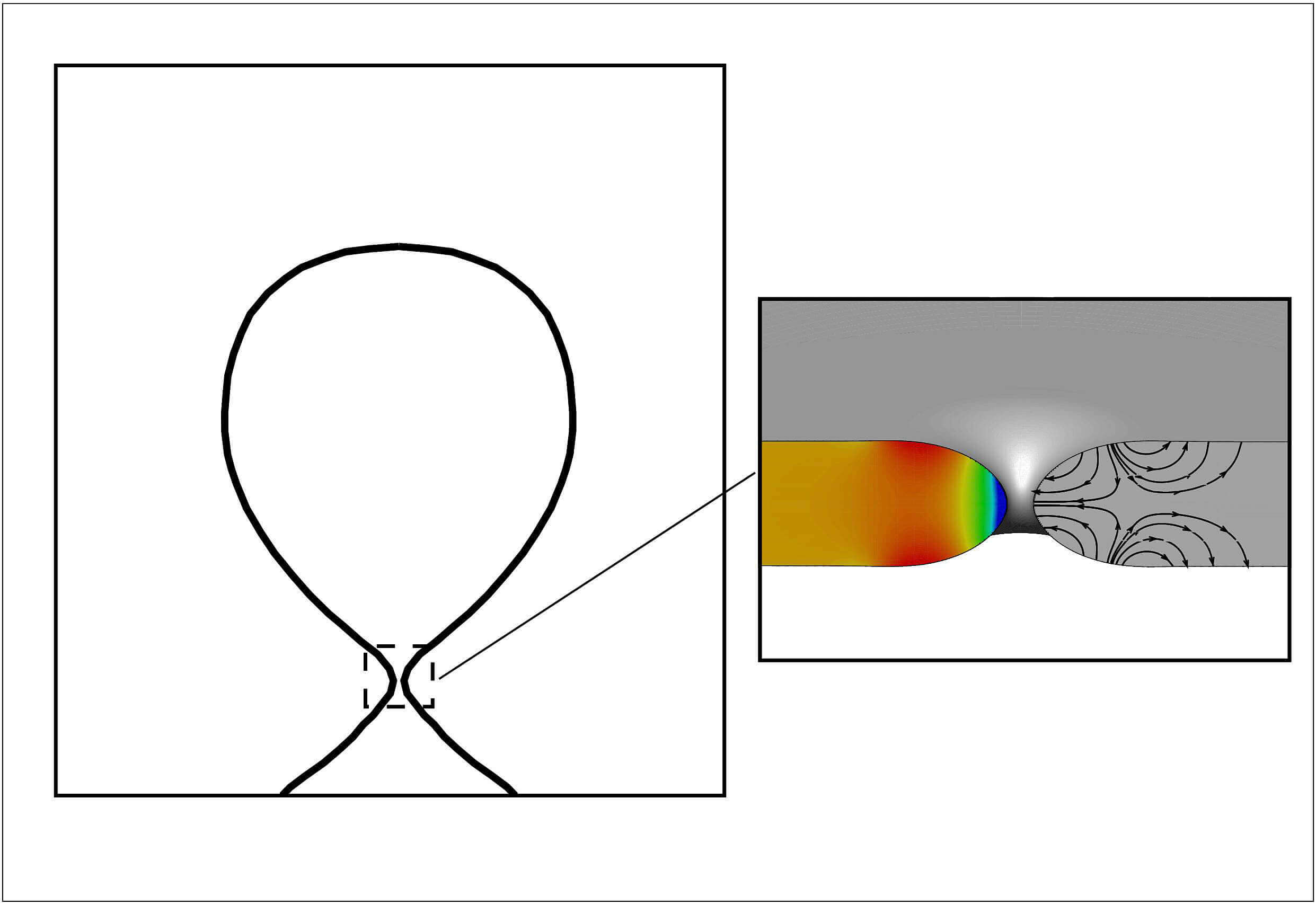

Carlos Corvalan and Jiakai Lu modeled the creation of microbubbles, which may be useful for cleaning food processing equipment with fewer chemicals and less water. An emerging microbubble before pinched off (left) is similar to a contracting pore (right), in which fluids are driven toward the neck from a high-pressure region (red) to a low-pressure region (blue) near the pore tip. (Photo courtesy Jiakai Lu)

Carlos Corvalan and Jiakai Lu modeled the creation of microbubbles, which may be useful for cleaning food processing equipment with fewer chemicals and less water. An emerging microbubble before pinched off (left) is similar to a contracting pore (right), in which fluids are driven toward the neck from a high-pressure region (red) to a low-pressure region (blue) near the pore tip. (Photo courtesy Jiakai Lu)