When teachers become the students: Four takeaways from the virtual classroom

As the semester draws to a close, faculty and instructors reflect on the many challenges pivoting to an online classroom due to COVID-19. Their chief conclusion? They’ve learned as much, if not more than their students while grappling with the ever-changing nature of higher education during a pandemic.

Whether a newly minted professor or veteran educator, most agree this is their strangest and most challenging semester to date. Many also believe, however, the time has not been without its merits and has offered valuable pedagogical lessons they can incorporate into future, in-person classes.

“There are things we can borrow from the online experience to enhance that in person experience,” Aaron Thompson, horticulture and landscape architecture assistant professor, said.

"When students can answer each other’s questions it leads to better learning outcomes all around.”

The “module” format may not be going away

Professors, instructors and students are all adjusting to the disparity of student situations. Students live in different time zones and abroad, may not have access to a computer 100 percent of the time or may be living at home where there is poor broadband. For that reason, instead of recording a 50 minute lecture and uploading it, professors started using the “module” format, short five to ten minute videos from the professor, explaining a seminal course component. This allows students to access the information, whenever they choose, engage with it repeatedly and digest difficult concepts in smaller chunks.

Instructors and professors like Jarred Brooke, FNR Extension wildlife specialist, found students engage better and often demonstrate enhanced understanding using this educational model. Brooke teaches a course about the ecology and management of controlled burns, a class that traditionally relied on the hands-on, field component. He said the modules he delivers online are similar to how he teaches in the field, but he has learned how to better tailor them to the classroom environment.

“I don’t see any circumstances where this permanently becomes an online class,” Brooke said. “But it will change how I teach the class in the future. The module format is a good way to reinforce what we did in the field and also give students access to information and reflections long after we’ve left the field.”

Thompson seconded this sentiment and said modules will likely become a regular facet of his teaching.

“One thing I’ve been surprised to see is how students are responding to these quick hit videos,” Thompson said. “Having the content available for them to grab when they are mentally prepared to receive it has been hugely beneficial.”

A module from Brooke's course:

The nature of feedback could change

Professors routinely offer feedback in all sorts of formats from comments in the margins of papers to talks after class. For Thompson, who is teaching a studio course in landscape architecture this semester, finding ways to offer constructive feedback proved challenging at first.

Traditionally, Thompson and the student would sit down and use trace paper and markers to evaluate the students’ design and suggest changing going forward. He has now developed methods for this “trace paper and marker operation” in the digital sphere. Additionally, the conversations aren’t as informal as those he normally has with his students, but Thompson finds having a record of those conversations, both for students and himself, has proved valuable.

“There is a more scripted sense to the process of feedback,” he continued. “Having the digital artifact of our conversations has proved useful and I think it is something I will continue to do when giving feedback. In the past, the record of the revisions and conversation was kind of lost, but this method really provides a fresh perspective for future conversations.”

Students are more resourceful than they realized

When a professor or instructor is immediately available either by email or in class, students tend to reach out quickly to ask for help. During COVID-19, everyone is less available and students are not always as quick to jump on email to ask a professor a question that may feel trivial. Students are discovering, however, given the space and time to wrestle with a problem they will often triumph on their own.

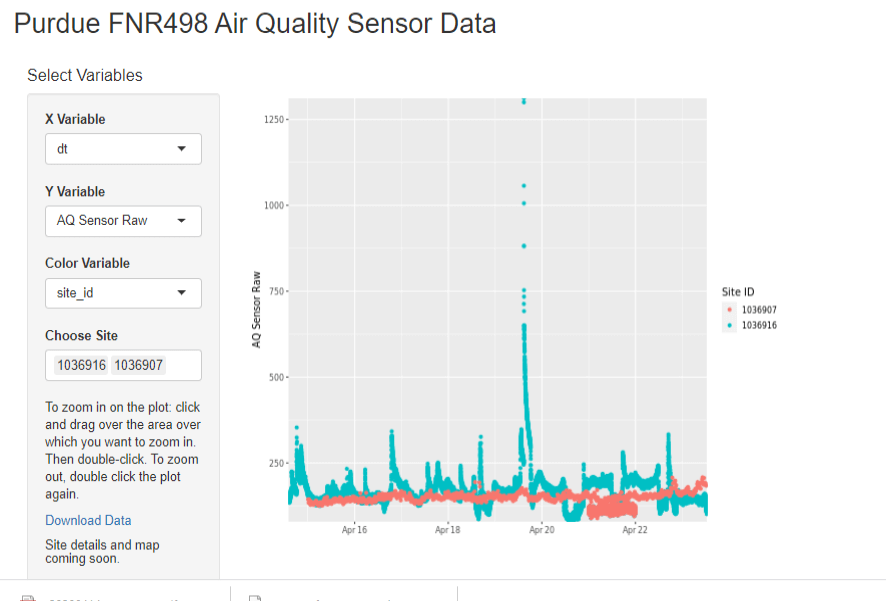

An aspect of the ecological sensors and data class taught by Jake Hosen, involves utilizing and collecting data from ecological sensors, in this case air quality sensors. Debugging and intuiting when the sensor is not behaving is a major part of the class and something students will encounter in the professional world. After sending all his students air quality sensors to design experiments, Hosen said he finds their problem-solving skills impressive.

“This has given students the chance to be more resourceful,” Hosen reflected. “They’ve been knocked for a loop for weeks, but they are becoming more resilient, relying on their problem-solving skills. I had a student email about a problem and by the time I’d emailed her back, she’d solved it. Just the few minutes she spent alone with her thoughts and the device was enough to figure it out.”

Students are each other’s best resource

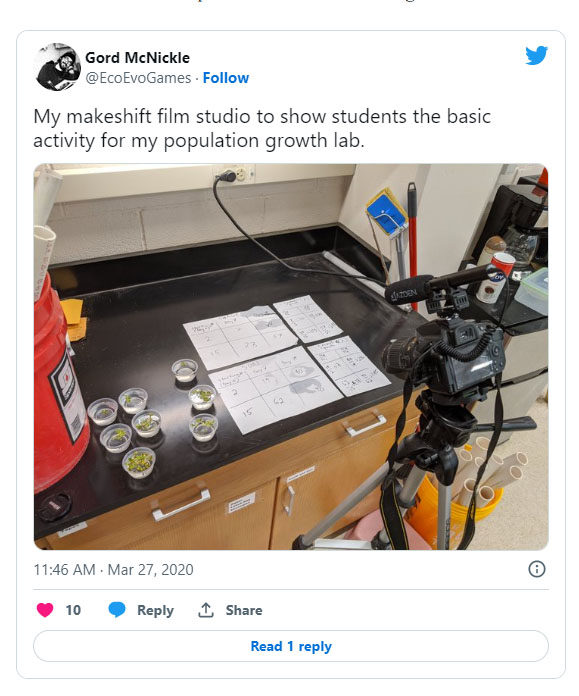

Like many, Gordon McNickle, botany and plant pathology professor, felt alarmed when he learned it would be necessary to take his 50 person, introductory botany course online. Not only is the course hands on, but McNickle worried about the density of questions he’d field from students.

To try to counter an onslaught of emails, he organized a Blackboard discussion board for students, a place they could go and talk to each other about material before coming to the professor. And the results surprised him. “It can be easier, less intimidating, to ask questions of a peer,” he said. “I’ve done this with graduate level classes but not undergraduate. When students can answer each other’s questions it leads to better learning outcomes all around.”