“Education is multidimensional”: How agriculture staff and students are reaching grades PK-12 during a pandemic

When life gives you lemons, make lemonade, or so the adage goes. But if you’re agricultural sciences education and communication (ASEC) graduate student Ryan Kornegay, it might be more appropriate to suggest; when life gives you cucumbers, make pickles.

Kornegay’s graduate work is focused on STEM education for elementary-aged students, fostering an interest in the fields through agriculture. “Agriculture is relatable to most people,” Kornegay said, “especially kids. Everyone has to eat.”

Ryan Kornegay with his pickle experiment

Before COVID-19 hit, he planned to take educational programming he’s developed around to schools in Indiana, but the pandemic thwarted his plans while also presenting new opportunities for engagement. Kornegay, like many others in the College of Agriculture, quickly reformatted his educational content to fit a virtual learning space. This semester, he offered several five-day STEM science camps to elementary aged students across the country and around the world.

The cornerstone of Kornegay’s program is making pickles from cucumbers, an exercise he says teaches students about fermentation and food preservation but that they also find fun.

He allows the students to flex their creative muscles by flavoring the pickles however they want. “We actually got Kool-Aid pickles once, which was interesting,” Kornegay laughed.

Megan Gunn, recruitment and outreach specialist for forestry and natural resources (FNR), said she also had to modify her usual programming for area high school students this semester due to COVID-19. Gunn works with high schoolers to spark-quite literally- their curiosity about their surroundings and local environs. One activity the students really enjoy is helping Gunn electrofish in streams, a technique used to stun and capture fish to sample their populations and determine water quality.

“It’s really opened my eyes to the advantages of virtual learning, both for educators and students. I want to continue to explore these possibilities even post-graduation.”

“In the past I would have students help me by holding the net and catching the fish while I shocked the fish,” Gunn explained. “We were still able to do an in-person demonstration, but this year they had to stay at a safe distance on the banks. I could still sense their excitement and interest in the process.”

This experiment is part of Gunn’s larger initiative to teach students about the species of plants and animals they live in harmony with, inspiring them to enjoy the outdoors and become stewards of the environment. In addition to her live demonstration, Gunn also visited classes virtually to discuss these issues and attended the students’ capstone presentations online about the environmental resources that exist around their schools.

Gunn also worked with the Tippecanoe County Partnership for Water Quality to adapt a field trip the students take to a virtual setting, where students could learn about the Wabash River and ask questions. “They were as engaged as they typically are when we’re physically on the river,” Gunn said. “They asked just as many questions, only this time it was through a chat function.”

Gwen Pearson, outreach coordinator for entomology, said it has been a challenge adapting some of her PK-12 grade programming for an online setting, especially because of the hands-on nature of her presentations. These activities are about teaching kids that insects are important and interesting, not gross and dangerous, and helping them unlearn some of their unconscious bias about the insect world.

“It’s a little more challenging now they can’t physically pet a caterpillar, but it still works,” Pearson reflected. “They see me holding a tarantula safely, and they are able to relax a little. And kids are made of questions; it’s not hard to get them going. That also let them feel like they had a little bit of control over the program, in a year when I think many of us felt like we couldn’t control anything.”

Gunn hosts a "Mondays with Megan" series on her Youtube channel for students and educators.

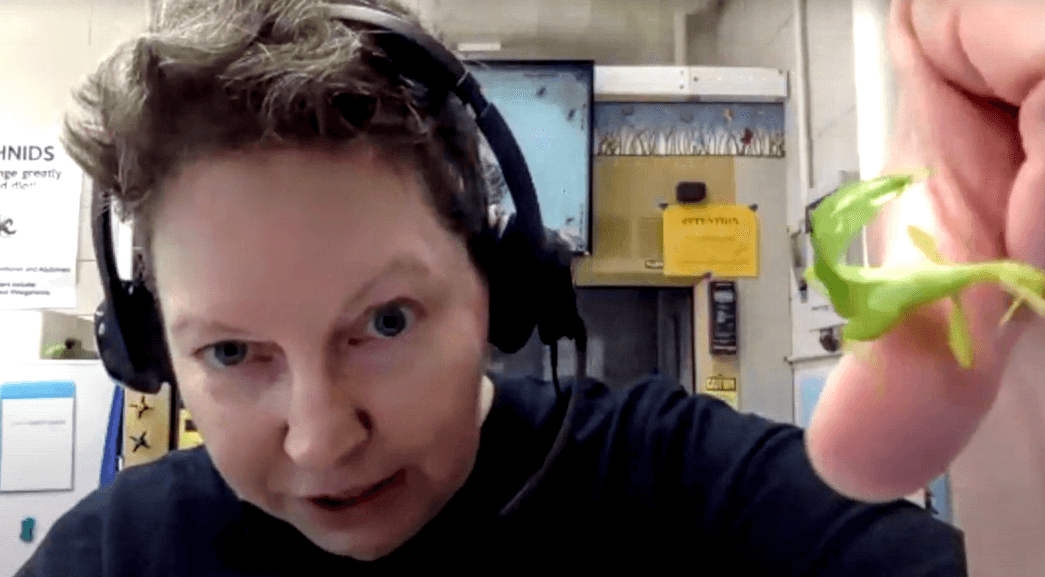

Pearson shows off a leaf bug to kids during a virtual classroom event.

Pearson has been able to connect with a host of different schools and classrooms this year, partially because the first thing her department did when COVID-19 hit was to cut away programming fees, knowing online educational resources were going to be essential in the coming months.

“With this much change and pressure on teachers, we wanted to be as supportive as we could. We also opened programs for students younger than we normally serve,” she added. “Because a lot of students joined us from home, we got to talk to a lot of parents. I think a lot of parents now have a better idea of just how difficult the work of a teacher is, and how special their skills are.”

Kornegay, Gunn and Pearson are all inspired by the engagement they’ve witnessed from students and educators during this difficult time. All three will continue to build on their virtual offerings, using the experiences from this semester to bolster programming, likely even beyond the pandemic.

to monitor population density and water quality.

“I have been able to reach so many students this semester because of my transition to online,” Kornegay said. “It’s really opened my eyes to the advantages of virtual learning, both for educators and students. I want to continue to explore these possibilities even post-graduation.”

Megan Gunn works collecting specimens to monitor population density and water quality.

Gunn seconds this observation, adding that the pandemic highlighted the need for engaging online materials, where students can interact with specialists they might otherwise never have a chance to meet. “We’re learning that education is multidimensional, it’s adaptable,” Gunn continued. “Virtually, you’re able to interact with more kids. It’s not just how many you can accommodate in the room, or when it might fit your schedule. Virtual learning can be on their time, at their pace.”

Of the many takeaways from this strange and stressful semester, Pearson said perhaps her greatest lesson is about herself, not just about what she can provide students but also how they enrich the lives of educators.

“I did not realize until I had been shut up in my house alone for a couple of months how much I really needed the energy of excited kids around me,” Pearson said. “Every time I did a virtual program, I felt 200 percent better about life. The kids got me through this.”