One giant leap for agriculture, students grow soybeans in lunar, Martian soil simulants

While growing crops on Earth can be complicated, growing vegetables on the Moon and Mars presents a whole different level of obstacles. A group of undergraduate students from the colleges of agriculture and engineering decided to undertake this mission through the Plant the Moon and Plant Mars challenges, competitions hosted by NASA’s Artemis Program seeking understanding of how scientists can grow crops for future space missions.

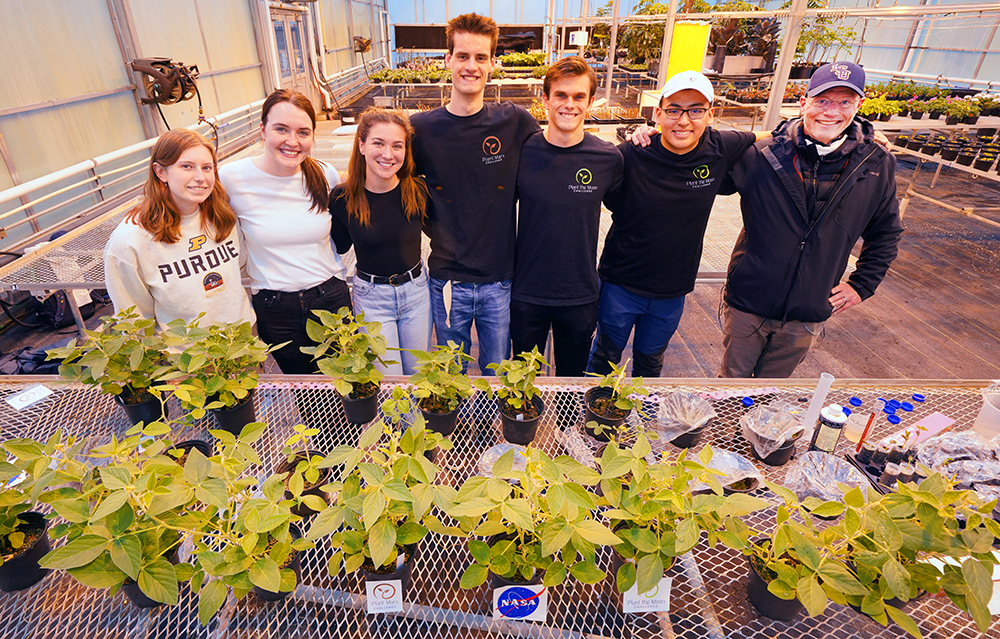

The team--Joshua Bailey, a junior in agricultural economics; Kyra Keenan, a junior in agricultural and biological engineering (ABE); Alessandro Paz, an ABE sophomore; Riya Raj, a sophomore in aerospace engineering; Madelyn Whitaker, an ABE sophomore; Brian Wodetzki, a sophomore in aerospace engineering and Autumn Wuebben, an ABE sophomore--spent their spring semester taking turns watering and caring for the plants, meeting a minimum of weekly to document research.

Bailey said the team chose to grow soybeans for both experiments due to their high protein content and to have a midwestern crop represented in the challenge. To purchase the soil simulants, the team applied to the Purdue Engineering Student Council Merit Fund for partial funding. The team’s advisor, ABE professor Marshall Porterfield, also contributed some of his own research funding and equipment.

Whitaker said the first few weeks of the growing process consisted of a lot of testing and discovery.

“A few weeks in we realized the Martian soil has perchlorates, which are really toxic chemicals to plants, which wasn’t made known to us when we received the simulants,” Whitaker said. “So, we actually had to wash the entire soil system for Mars and replant because the soybeans were deteriorating.”

The team also needed to consider the lack of a microbiome in outer space.

“When we're farming on the Moon or Mars, or in this case in their simulants, one of the most important aspects to consider is that there are no symbiotic organisms present in their regolith,” Keenan said. “Symbiotic organisms are crucial for maintaining plant health and carrying out nitrogen fixation, a process that converts nitrogen from our atmosphere into usable forms for the plant. Our soybean seeds were coated in a film that contained rhizobia, which is a bacteria that facilitates nitrogen fixation, but we further enriched our soils by using a fertilizer.”

Contrary to the Martian simulant, Keenan said the lunar simulant plants performed well and were on track to grow larger than the Earth plants. But Bailey wondered if the difference was due to the density of the Earth soil they used, which was taken from a local field in the middle of February.

Bailey said the team purposely minimized the use of outside resources, knowing that if astronauts were to attempt to grow crops in outer space, the space within the spaceship would be sparce.

“We structured our experiment to mimic a mission in space where there would be minimal supplies to use for growing plants. Therefore, we decided to treat the plants with as little water/fertilizers as possible each day,” Bailey said. “There was a time when the plants were drooping because their growth had exceeded the additives we were supplying, but the next day after upping the amount given, they were back to normal. It's been interesting to learn how well the plants could grow, even when being pushed to the limit.”

During an awards ceremony on May 16, the group was awarded the undergraduate level “Best in Show for Experimental Design.” Bailey said for his team to receive recognition for this semester’s work was a true honor.

“We're extremely proud to represent Purdue in this increasingly important field and to have been recognized for all the hard work we've put in,” Bailey said. “Space agriculture is critical in creating future sustainable space missions and I think our multidisciplinary team has shown that we're here to contribute to this development.”