From centuries-old, hand-drawn maps to LiDAR lasers & the role of both in forestry

An army of bow saws and boots march through dense thickets of forest patches in the Chicago region, cutting away greenery in the city and its outskirts. This army actually consists of volunteer environmentalists willing to do whatever they can to take down some buckthorn for the preservation of other trees.

Buckthorn is an invasive species, brought to America by Europeans as early as the 19th century for its capacity to grow fast and form dense hedges for privacy. Now, it’s taken over forests—choking native species out. The story of dangerous invasives isn’t new, but scientists like Brady Hardiman in the Institute for Digital Forestry, are fighting the centuries-old problem with tools both as old as the problem and others that sound like science-fiction.

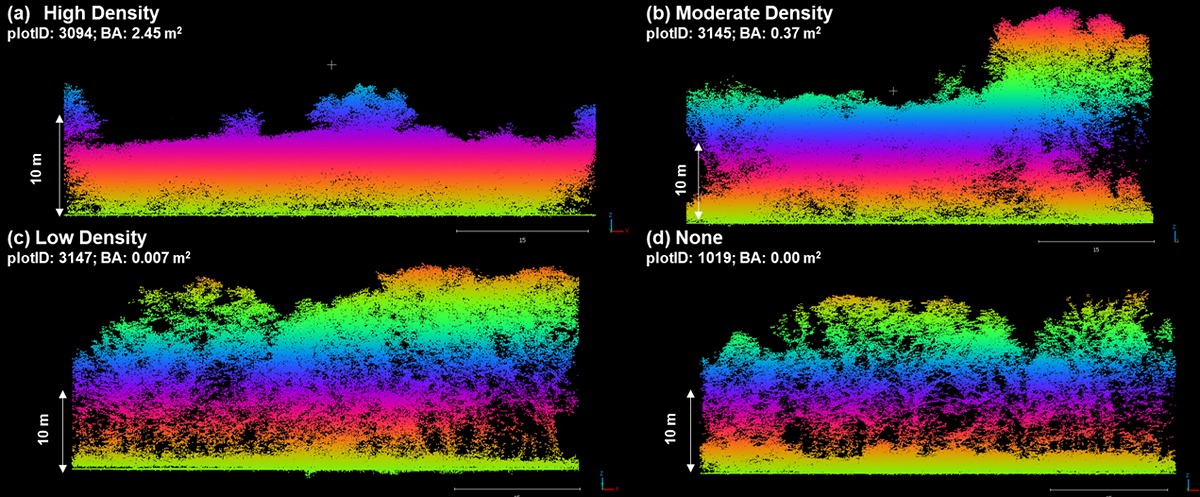

“LiDAR is like radar, but with lasers,” Hardiman explained. “It can be deployed in a variety of mobile and stationary ways, like backpacks, tripods, drones and conventional aircraft. LiDAR operates by shooting laser pulses at the ground. Those bounce back and a timer measures how long it took for the light to travel back, so you can make accurate maps, called point clouds, that show the height of every object the lasers touch.”

In Hardiman’s lab, they use these point clouds to see the structure and distribution of different vegetation types. Invasive species, like buckthorn, form a canopy that is so uniform and thick that they appear on the maps like an impenetrable wall. Old-growth forests, on the other hand, allow enough sunlight to reach the ground that small flowers and saplings can grow, giving their canopy a more complex point cloud.

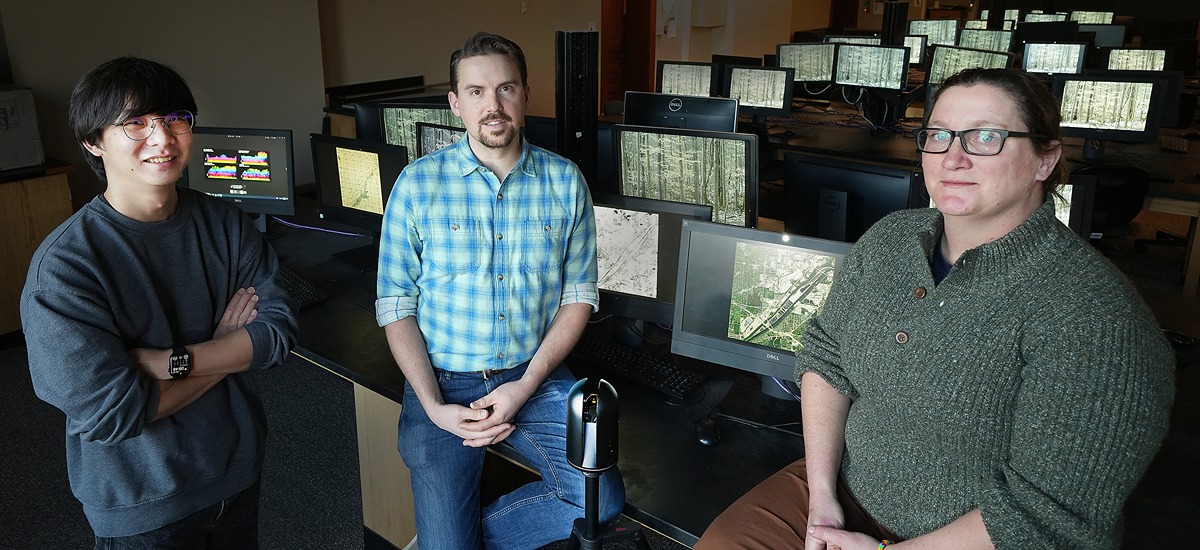

Dennis Choi from the Hardiman lab makes these point clouds using LiDAR. The height and diversity of forests are constructed from the data collected by sending out lasers and timing their return after they bounce off a surface. These point clouds show how a forest changes with different densities of Buckthorn, an invasive plant species that prevents other native plants and trees from growing.

Dennis Choi from the Hardiman lab makes these point clouds using LiDAR. The height and diversity of forests are constructed from the data collected by sending out lasers and timing their return after they bounce off a surface. These point clouds show how a forest changes with different densities of Buckthorn, an invasive plant species that prevents other native plants and trees from growing. LiDAR has been an essential tool for many projects in Hardiman’s lab, including that of Lindsay Darling, who recently earned her doctorate from Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources. Darling is also the GIS and Data Specialist at The Morton Arboretum and a volunteer buckthorn-fighter in Chicago, where she studied how urban forests have changed over time and how that has affected the people of the region.

Prior to colonization, the Ojibwe, Odawa and Potawatomi tribes burned the prairies of northern Illinois. Darling explained. “Fire promoted more of a prairie landscape, and it encouraged the plants and animals that were important to them, like oaks. Oak saplings have very deep roots to resprout after fire, and the big trees have thick bark, so surface fire doesn't really hurt them. Animals eat acorns, oaks change the soils and have relationships with other fungi. If oaks do well, then all the other plants and animals can do well.”

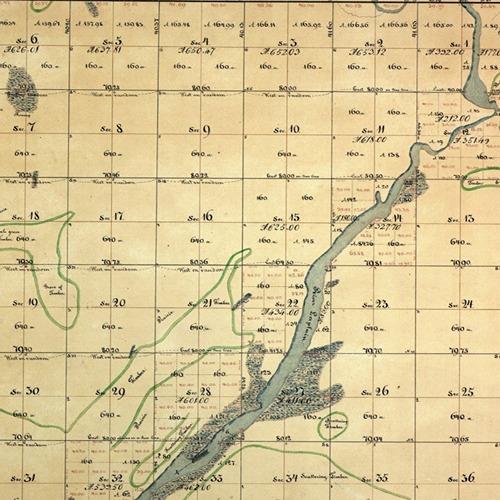

The forests taken from Indigenous peoples were first recorded on maps in the 1830s. The federal government sent surveyors across the Midwest to map the land, identifying features that would make it easy for colonists to recognize their section of land. On their way, they drew maps of the land, recording the locations of rivers and taking note of the species and sizes of trees around.

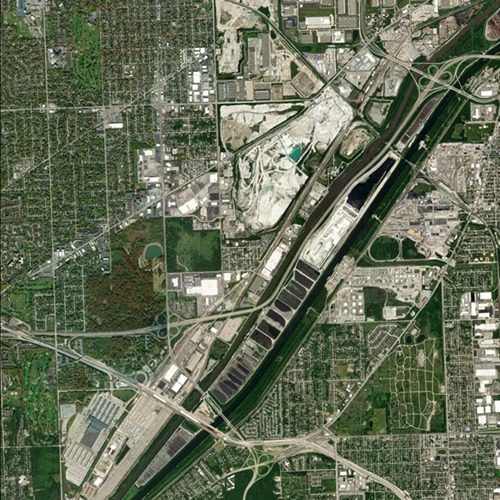

Darling took these centuries-old, hand-drawn maps as well as aerial images taken in the 1930s and compared those with current aerial imagery and canopy structure made from LiDAR data. She was able to reconstruct the story of Chicago’s forests and connect it to the stories of people living there today.

Darling compared maps from different centuries of the Chicago region to show how the ecology and forests changed over time. These three maps, one hand-drawn from the 1830s (left), one photographed in the 1930s (middle), and a modern satellite image (right), are all of the same region of land around the Des River.

Darling compared maps from different centuries of the Chicago region to show how the ecology and forests changed over time. These three maps, one hand-drawn from the 1830s (left), one photographed in the 1930s (middle), and a modern satellite image (right), are all of the same region of land around the Des River. Most of the beneficial oak forests were replaced by infrastructure as the city grew. Darling calls the few remaining “remnant” forests. There are also “regrowth” forests, where the oak forest was once destroyed but has since regrown. “Novel” forests exist where oak forests never grew and tend to have a lot of invasive species, like buckthorn.

“I conducted field sampling throughout the area. These forest types are really different from each other,” Darling commented. “The remnant ones still have a lot of oak character, and that was what was important to the region. Regrowth patches have some oak and maple but a lot of invasive species. Novel forests are super homogeneous, like flat smears of trees, and are less able to provide ecosystem services.”

After comparing the distribution of the different forest types to the percentage of white and non-white people in the area, it became clear that remnant forests and their benefits were most available to those that were white. People of color tend to live around pockets of novel forests that don’t offer the ecosystem services, like the cooling properties and health benefits that oak forests do.

Hardiman is both proud of Darling for completing her doctorate in his lab and a little sad to see her leave it. “Lindsay has been an exceptional student and collaborator in a way that any advisor hopes for. Her work is novel, interesting and important for real people in the real world. I think it will make a difference, and I'm looking forward to many years of collaborating with Lindsay in the future.”