Forestry & Natural Resources

FNR Assists in First Natural Breeding of Eastern Hellbender in Captivity

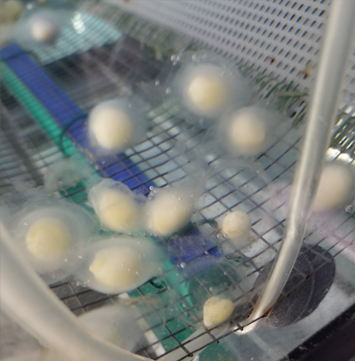

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - Oct. 7, 2020, was a historic day at Mesker Park Zoo & Botanic Garden as a nest full of eggs was found in an artificial breeding stream as part of morning checks of the resident Eastern Hellbender population. This momentous occurrence at the zoo in Evansville, Indiana, marks the first time that Eastern Hellbenders, the largest salamander in North America, have bred naturally in captivity and signifies the culmination of a long and collaborative effort to breed the species and restore this endangered species to its native environment.

The historic breeding has produced 68 fertile eggs. It will take an estimated 72 days for those eggs to hatch into larvae. The hatched larvae, typically between one and two inches long, will retain their yolk sacks for nutrients for another several months. The larvae will develop legs over time and eventually lose their external gills by age two. Hellbenders have a lifespan of more than 30 years.

“It was very, very exciting,” assistant curator Leigh Ramon said of the moment the eggs were discovered. “A radio call went out and a picture pretty quickly after and cheers rang out over the radio immediately from all of our staff. Even the people who aren’t working full time on the project were incredibly excited. I think everybody realizes how monumental this is and kind of a game changer, hopefully. Being able to breed them in captivity will allow us to get larger numbers back out into the wild. I think it is a really big deal that we created something that can contribute back to the population and keep it from disappearing.”

“It was very, very exciting,” assistant curator Leigh Ramon said of the moment the eggs were discovered. “A radio call went out and a picture pretty quickly after and cheers rang out over the radio immediately from all of our staff. Even the people who aren’t working full time on the project were incredibly excited. I think everybody realizes how monumental this is and kind of a game changer, hopefully. Being able to breed them in captivity will allow us to get larger numbers back out into the wild. I think it is a really big deal that we created something that can contribute back to the population and keep it from disappearing.”For animal curator Susan Lindsey, the find brought excitement and a bit of anxiety as the group approached an unknown future. First, would the eggs be viable and then the waiting game for them to hatch, a timeline which can be quite variable depending on size and other factors.

“For me, on a personal level, there was great excitement, but also trepidation about the huge responsibility we had there,” Lindsey said. “I was on pins and needles for the two weeks (from the discovery to extraction from the nest) about if things would go well, making sure he (the father) didn’t eat the eggs and that he was still protecting them. It also made me think back to the year I came to Mesker (Park Zoo), which was the year that the Saint Louis Zoo had their success (breeding another subspecies). I had hoped that we would be able to do something along those lines, and then to look now and see this success, it is just pretty phenomenal.”

There are two subspecies of Hellbender, the eastern hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis alleganiensis) and the Ozark hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis bishopi). The eastern hellbender is a large, fully aquatic salamander, nicknamed the snot otter, water dog, devil dog, Allegheny alligator and water eel among other things. At maturity, the species can measure approximately two feet long.

Characterized by flat bodies and heads, slimy blotchy brown skin with folds along the sides that are often said to resemble lasagna noodles, and long tails, eastern hellbenders live in shallow, fast-flowing, cool, rocky rivers and streams across the United States from New York to Georgia and as far west as Missouri and Arkansas.

Characterized by flat bodies and heads, slimy blotchy brown skin with folds along the sides that are often said to resemble lasagna noodles, and long tails, eastern hellbenders live in shallow, fast-flowing, cool, rocky rivers and streams across the United States from New York to Georgia and as far west as Missouri and Arkansas.Eastern hellbenders breathe through capillaries near the surface of their skin, absorbing oxygen directly from the water. This requires high quality streams and the species has struggled to survive after decades of declining water quality and habitat degradation.

The Saint Louis Zoo was the first to breed Ozark hellbenders, the other subspecies of hellbender, doing so back in 2011. The Nashville Zoo was the first to successfully hatch eastern hellbender eggs using artificial insemination in 2012. They repeated the feat in 2015 using cryopreserved sperm (another first.)

The Journey to Breeding in Captivity

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources’ Rod Williams has dedicated much of the last eight years to eastern hellbender husbandry, or the rearing of this ancient animal in captivity and their eventual return to the wild. One feat that had never been accomplished however, was to breed the eastern hellbender naturally in captivity.

Purdue Forestry and Natural Resources’ Rod Williams has dedicated much of the last eight years to eastern hellbender husbandry, or the rearing of this ancient animal in captivity and their eventual return to the wild. One feat that had never been accomplished however, was to breed the eastern hellbender naturally in captivity.

Mesker Park Zoo approached Williams in 2015 with hopes that the facility could help with the project. Williams accepted the offer and hoped the new partners might be able to make headway on the breeding front.

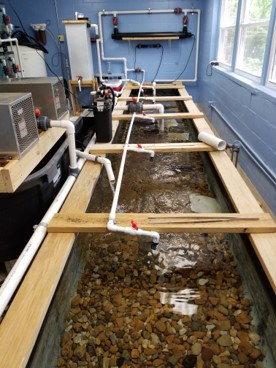

In 2016, the zoo began preparations for the construction of an artificial stream, or raceway, which is meant to simulate the habitat of the Blue River and would hopefully serve as a breeding ground for the hellbenders in captivity. In 2017, the first adults were put into the artificial stream, which measures 22- feet, 1-inch long, 4 feet wide and 2.5 feet deep.

In 2016, the zoo began preparations for the construction of an artificial stream, or raceway, which is meant to simulate the habitat of the Blue River and would hopefully serve as a breeding ground for the hellbenders in captivity. In 2017, the first adults were put into the artificial stream, which measures 22- feet, 1-inch long, 4 feet wide and 2.5 feet deep.Over the next four breeding seasons, alterations were made annually to create favorable conditions for breeding. This included changing the male:female ratio in the stream and also adjusting water quality parameters.

In 2019, a third female hellbender, brought in by Williams through a partnership with The Wilds in Columbus, Ohio, and the West Virginia Department of Natural Resources, was added to the stream just ahead of breeding season. Zookeepers saw a lot more activity and interaction between individual salamanders than in previous breeding seasons, but no eggs were produced. In 2020, some finishing touches were made to the artificial stream and the historic clutch of fertilized eggs was produced.

“Right before breeding season, we got some updated information on the nest site that Nick (Burgmeier) had taken eggs from in Kentucky to rear in captivity,” Ramon said. “He took a temperature reading there. We had been using historic Blue River records to follow temperature and seasonality for our stream. The temperature reading he brought was quite a bit lower than what we had, so the temperature was dropped in our stream. We also dropped the phosphate levels quite a bit a few weeks before we saw the eggs. I think the social dynamic in the stream changed things quite a bit as well with more females in the stream.”

The sire of the historic eggs, Knick, was the sole caretaker of the clutch for their first two weeks of development. On October 21, the eggs were moved to a specialized tank where zoo staff can monitor their development more closely.

The exact identity of the mother is undetermined because females leave the nest after egg laying, which often takes place at night. There are three adult female hellbenders in the Mesker Park Zoo stream, the original female Tiamat, who arrived in December 2016; X-23 who was brought directly from the Blue River in 2018; and Matilda, the newest arrival who came from The Wilds just ahead of breeding season in 2019.

The exact identity of the mother is undetermined because females leave the nest after egg laying, which often takes place at night. There are three adult female hellbenders in the Mesker Park Zoo stream, the original female Tiamat, who arrived in December 2016; X-23 who was brought directly from the Blue River in 2018; and Matilda, the newest arrival who came from The Wilds just ahead of breeding season in 2019.Eastern hellbenders are one of the few salamander species to externally fertilize eggs. As the female begins to deposit eggs under the male’s chosen nest rock, the male will simultaneously release sperm to fertilize the clutch of eggs.

“This has never been done before but shows us that it is possible,” said Burgmeier, Purdue research biologist and Extension wildlife specialist, who captured the adult hellbenders that are being bred at the zoo. “If it can be replicated, then it could provide a long-term, reliable source of eggs for us to Help the Hellbender repopulate rivers in southern Indiana and throughout their range.”

Successful Partnerships

The captive breeding efforts were made possible by long-term support from the Evansville Zoological Society. Grant funds that helped construct the hellbender facilities were received from Aquarium and Zoo Facilities Association’s Clark Waldram Conservation Fund, Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium’s PPG Conservation and Sustainability Fund, and Association of Zoos and Aquariums Amphibian Taxon Advisory Group’s Small Grant Fund.

The captive breeding efforts were made possible by long-term support from the Evansville Zoological Society. Grant funds that helped construct the hellbender facilities were received from Aquarium and Zoo Facilities Association’s Clark Waldram Conservation Fund, Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium’s PPG Conservation and Sustainability Fund, and Association of Zoos and Aquariums Amphibian Taxon Advisory Group’s Small Grant Fund.

Bryan Plis and Sean Wolak are the main zookeepers that work on the hellbender project at Mesker Park Zoo, but over the five years, many staffers have been involved in helping achieve the goal of natural breeding in captivity.

“It is absolutely a collaborative win,” Lindsey said. “We have lots of meetings with the hellbender folks across the country. Honestly everyone coming together and talking through what they are doing makes a really big difference. They freely share the information that they have. The Saint Louis Zoo also was willing to share their successes and failures with us so we had a good place to start from. There is no direct route to this (breeding). There were a lot of meanderings off to the side and which ones made the most difference, it is hard to piece that out at this point, but there is no way this would have happened without everybody.”

Williams and his lab captured five of the six hellbenders involved in breeding at Mesker Park Zoo (three males and two females, all of which were captured in the Blue River between 2015 and 2018) and were instrumental in coordinating the procurement of the third female from West Virginia through the relationship with The Wilds.

Williams and his team along with staffers from the Ron Goellner Center for Hellbender Conservation at the Saint Louis Zoo have worked with the Mesker Park Zoo curators over the years to tweak their habitat conditions to emulate the natural environment as much as possible as hellbenders require cold, clean, fast flowing water.

“The Mesker Park Zoo team found the funding, put in years of work and had the expertise required to assist in the breeding efforts,” Williams said. “This accomplishment, which had never been achieved to date by any zoo or other entity in the world, just goes to highlight that partnership is key to successful conservation efforts. Every partner played a role in getting to this point and I am excited for what the future holds.”

Resources:

For more information on the eastern hellbender, visit the Help the Hellbender website.

The Hellbender was highlighted by the Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife in its promotion efforts for the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

Story Map and Releasing hellbenders in the Blue River

Help the Hellbender was also featured on the cover of the January/February 2019 issue of Outdoor Indiana.

Learn about hellbenders and take a tour of Purdue’s hellbender rearing facility

Learn about the hellbender work at Mesker Park Zoo.

Learn about hellbender work at The Wilds.

View Dr. Rod Williams’ 2017 TEDx Talk on hellbenders.

A Moment in the Wild: Hellbender Hides

A Moment in the Wild – 2020 Hellbender Release

For information on the Saint Louis Zoo’s successful breeding of the Ozark Hellbender in 2012:

Endangered Ozark Hellbender Salamanders Breed in Captivity for the First Time

Quantitative Behavioral Analysis of First Successful Captive Breeding of Endangered Ozark Hellbenders

For more information on the eastern hellbender, visit the Help the Hellbender website.

The Hellbender was highlighted by the Alliance for America’s Fish and Wildlife in its promotion efforts for the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act.

Story Map and Releasing hellbenders in the Blue River

Help the Hellbender was also featured on the cover of the January/February 2019 issue of Outdoor Indiana.

Learn about hellbenders and take a tour of Purdue’s hellbender rearing facility

Learn about the hellbender work at Mesker Park Zoo.

Learn about hellbender work at The Wilds.

View Dr. Rod Williams’ 2017 TEDx Talk on hellbenders.

A Moment in the Wild: Hellbender Hides

A Moment in the Wild – 2020 Hellbender Release

For information on the Saint Louis Zoo’s successful breeding of the Ozark Hellbender in 2012:

Endangered Ozark Hellbender Salamanders Breed in Captivity for the First Time

Quantitative Behavioral Analysis of First Successful Captive Breeding of Endangered Ozark Hellbenders

For information on the Nashville Zoo's successful eastern hellbender breeding with artificial insemination: