May 10, 2012

Investment and Financing Behavior of Farmers: Responding to Boom and Bust Times

The Set-Up

Although the U.S. farming sector has exhibited very strong financial performance during the past 5-7 years in terms of income generation, cash flow and debt servicing capacity, and equity accumulation, that strong performance has been accompanied by increased risk. This increased risk is a result of increased volatility in crop and livestock product prices, input costs and product output (due to both more variable climatic conditions and losses from increased pest/disease outbreaks) that has created more operational risk for farm businesses. Even though the volatility of prices as a percentage of the average price has not changed much compared to the past, higher costs and the fixed nature of some of these costs has increased the volatility of both operating margins and net income on both an absolute and relative basis dramatically.

The amount of leverage (debt relative to equity capital) used in the industry has declined over the last two decades, suggesting that the financial risk for the sector is less than it was, for example, in the 1980’s. But industry averages may not accurately reflect the true financial risk for individual firms or even for the industry. Larger scale growing farmers who generate the majority of the agricultural output have leverage positions as reflected by the debt to asset ratio more than three times the industry average of 10 percent. Furthermore, interest rates on debt are at abnormally low levels, and when they rise will increase the debt servicing requirements for farmers who have not converted from variable to fixed rate loan terms. Operating credit lines have increased for many producers, and interest rates on these loans are reset at renewal and when will increase if market rates rise. And some farmers have signed longer term (3-5 year), high fixed rate cash rent leases to obtain control of land rather than purchase that land – these arrangements result in fixed cash flow commitments irrespective of productivity and prices much like a principal and interest payment on a mortgage. Farmers are also facing more strategic risks than they have in the past – disruptions in market access and supplier relationships including loss of a lender relationship or a landlord, regulatory and policy changes, food safety disruptions and reputation risk, etc.

U.S. agriculture is notorious for its boom and bust cycles and now appears to be in the midst of another golden era. Strong global food demand and robust biofuels markets have strained the current production capabilities of global agriculture. The prospects of tight global supplies well into the future have spurred booming farm incomes. Historically low interest rates have quickly capitalized these burgeoning incomes into record high farmland values. But past golden eras in agriculture quickly faded – the most recent being the decline in the 1980s from the boom of the 1970s. The promise of sustained global demand shifted with economic conditions, and capital investments in agriculture led to increased agricultural supplies that trimmed farm prices and incomes. At the same time, leaner farm incomes were unable to support the record-high farmland prices, especially at higher interest rates. As a result, many farmers that worked to seize the emerging opportunities were left empty-handed as market and financial conditions changed. Will this time be different – will this boom not be followed by a bust for the agricultural sector? Understanding the investment and financing incentives and behaviors/responses of farmers in boom and bust times may provide insight into the answer to this question.

An Analytical Framework

A well accepted framework for understanding investment and financing behavior of farmers are the classic capital budgeting techniques focused on income and cash flow (internal rate of return, net present value or discounted cash flow, debt service repayment capacity, etc.). Unrealized capital gains or losses are not explicitly or implicitly recognized in this framework. Some have argued that unrealized gains (losses) have value because they add to (subtract from) the wealth position of the owner (the wealth effect). And others suggest that unrealized gains increase and losses decrease the financial base for acquiring credit and increase (decrease) the borrowing capacity of the business (the leverage or credit effect).

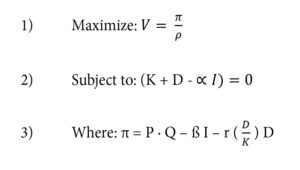

Lowenberg-DeBoer and Boehlje suggest a theoretical framework that acknowledges the impact of unrealized capital gains or losses on firm decision-making. In its simplest form, this framework builds on Vicker’s arguments that a firm maximizes wealth accumulation subject to a capital constraint as defined in equations 1), 2) and 3) below:

where V is wealth as defined by the present value of the stream of net income of the firm, π is the expected annual net income, ߩ is the discount rate, K is the equity capital of the firm, D is the debt capital of the firm, ∝ is the financial capital absorbed by each input, I are the inputs or resources used in the production process, P is the price of output, Q is the quantity of output produced by the firm, ß is the cost of the inputs, and r is the cost of debt.

Recognizing the impact of capital gains and losses on optimizing behavior requires adding the wealth effect and the leverage effect to the model. Adding the wealth effect results in respecification of the objective function of equation 1) to:

Where Ø is the proportion of unrealized capital gain or loss that is equivalent to current income, and G is the capital gain or loss.

Adding the leverage effect results in respecification of the capital constraint of equation 2) to:

Where μ is the proportion of unrealized capital gain or loss the debt market recognizes.

A more complete specification of this analytical framework and the comparative statistics implications of the constrained optimization under different assumptions is provided by Lowenberg-DeBoer and Boehlje. Their results indicate that

“in an environment of large capital gains, farmers will tend to enlarge farm acreage and incur higher debt loads in their attempts to take advantage of the farmland appreciation. If equity is a constraining factor, the model suggests that farmers will tend to use more highly leveraged financial structures when land prices are rising… Capital losses have the opposite effect of capital gains. The magnitude of these effects is an empirical question, but it should be noted that the model is broadly consistent with the farm size expansion and greater debt use that occurred during the period of farmland capital gains in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s.”

“Decisions by public and private sector lenders also can affect the impact of capital gains and losses… increasing the proportion of unrealized gains that they are willing to accept as net worth in the financial negotiation, lenders tend to increase total returns to land and offer incentives to increase farm size and the debt load. The model thus suggests that the statutory increase in 1971 of the maximum Federal land Bank loan from 65% of normal agricultural value, which was usually below market value because it was based on past prices in an inflationary period, to 85% of an appraised value based on market prices for farmland may have encourage farm expansion and more debt use by allowing a larger amount of unrealized gain to be monetized in refinancing agreements. Private sector lender behavior is hard to document, but casual observation suggests that during the 1970s commodity boom, when growth potential in the demand for farm products and hence increase in farmland prices appeared unending, agricultural lenders in general became more willing to consider farmland price increases as permanent additions to net worth than they had previously. In doing so they may have contributed to the situation which led to the financial stress of the early 1980s.”

“Lender treatment of capital losses may be an important variable in how the farming sector emerges from the current financial stress. If a large proportion of the loss is treated as permanent when it occurs, then there will be continued pressure to reduce the growth in farm size, trim debt use, and intensify farming. This may force more land on the market, further depressing prices. These changes may be seen as socially desirable, but the adjustment cost may be high if the capital losses are recognized quickly.”

The Insights

What insights does this analytical framework provide concerning the current period of prosperity in agriculture and the prospects for a boom and bust? How might future events evolve that would create a 1970’s-80’s boom – bust cycle?

Similar to past farm booms, today’s low interest rates have fostered the capitalization of rising farm incomes into record high farmland values. Accommodative monetary policy by the Federal Reserve has pushed nominal interest rates to historic lows. The capitalization of incomes into farmland values has accelerated, with the average price of U.S. farmland rising 25 percent from 2004 to 2011. The surge in U.S. farmland prices has outpaced the rise in cash rents. In fact, the average farmland price-to-cash rent multiple, which is similar to a price-to-earnings ratio on a stock, surged to a record high of almost 30 in various Corn Belt states (Gloy and others).

U.S. farm debt accumulation has not accelerated as it did during the 1970s. The primary lenders to U.S. agriculture – commercial banks and Farm Credit Associations – report limited expansions in farm lending. According to data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Consolidated Report of Conditions and Income, farm debt outstanding at commercial banks has held steady since 2009 (Henderson and Akers). The Federal Farm Credit Banks Funding Corp. indicates that lending on real estate mortgages, production, and other intermediate loans by Farm Credit System institutions rose a modest 3 percent during the 12 months ending in September 2011.

But the financial markets do present a future risk to farm debt use and leverage. Higher interest rates could have two distinct impacts on U.S. agriculture (Henderson and Briggeman). Rising interest rates may place upward pressure on the dollar, which could indirectly trim U.S. agricultural exports, farm profits, and farmland prices. In addition, higher interest rates also boost the capitalization rate, which weights further on farmland prices. The impacts are compounded in highly leveraged environments when higher interest rates raise debt service burdens, as the 1920s and 1980s demonstrated.

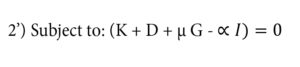

The ability of farmers to maintain low financial leverage while confronting narrower profit margins might be essential to agriculture’s future prosperity. Agricultural crop prices are expected to retreat in coming years as farmers boost production in response to today’s profitability. Combined with rising input cost projections, farm profit margins are expected to narrow in coming years. For example, net margins to corn production could fall almost 30 percent by 2013, with similar profit declines in other major crops (Chart 1).

When profit margins narrowed in the late 1970s, farmers leveraged up their farm enterprises as real interest rates remained historically low and gross farm revenues remained elevated. If profit margins narrow and interest rates remain low, farmers might repeat the patterns of the 1970s and leverage the farm. Then as in the early 1980s, a higher interest rate environment would increase the risk and farmers could struggle to service mounting farm debt.

An additional concern is that farmers may have more debt than some analysts project. According to USDA, U.S. farm real estate debt is projected to fall almost 3 percent in 2011. Commercial banks and Farm Credit Associations, however, indicate that farm debt is still on the rise. During the first three quarters of 2011, farm real estate debt in the Farm Credit Associations and commercial banks rose 4.4 percent and 0.6 percent, respectively, above year ago levels. In addition, non-real-estate debt at Farm Credit Associations and commercial banks also edged up. And the distribution of debt among farmers is important. Recent analysis of the financial condition of farmers indicates that those who are younger (less than 35 years of age) have significantly higher debt loads and debt to asset ratios than the industry average. (Briggeman 2011a; Ellinger 2011). And as indicated earlier, larger and rapidly growing farmers are more highly leveraged than the industry average. A future risk is that farmers could be increasing their leverage just as export growth and farm profits begin to slow.

Where to From Here?

How might events evolve from here? As suggested by the analytical framework, farmers are likely to continue to be aggressive in buying land and bidding up land prices to not only acquire the income stream from that land, but also to capture the wealth effect benefits of capital gains resulting from rising land values. These purchases are most likely made by larger growth oriented farmers who have higher leverage positions. Even if they have sufficient cash to make sizeable down payments, this transaction does change the structure of the balance sheet by reducing current assets while increasing non-current assets, and adding to current liabilities by the amount of the annual principal and interest debt servicing requirement. Thus, the liquidity position of the business as defined by working capital or the current asset/current liability ratio is reduced, making these firms more vulnerable to income shocks.

At the same time, farmers who are expanding rapidly have also been aggressive bidders in the land rental market — fixed cash rental arrangements have become increasingly common and many of these agreements are for multiple years (3-5 years) at relatively high fixed rates. These high multi-year cash rents result in increased future fixed cash costs much like mortgage obligations on land debt. These “pseudo-debt” financial obligations are typically not reported on the balance sheet, but they are similar to capital lease obligations which increase the leverage and typically reduce the working capital/liquidity position of the business. Strong cash positions and concerns about high tax liabilities have also resulted in significant purchases of depreciable machinery and equipment, which has again moved assets from the current to non-current category without restructuring the liabilities, thus creating an additional imbalance in the balance sheet. And the higher prices of fertilizer, seed, chemicals and fuel have resulted in larger operating lines, which increases the leverage and reduces the liquidity position even further.

This increasingly misaligned balance sheet with a higher portion of current vs. non-current liabilities contrasted with a lower portion of current vs. non-current assets increases the vulnerability of the business to income shocks from lower prices, lower yields or higher costs. Such shocks would decrease margins and cash flows as well as inventory positions, and could quickly result in a working capital position below lender underwriting standards. A typical response of the lender in this situation is to suggest liquidating inventories and using the proceeds to reduce operating debt. But for farmers who file Schedule F tax returns, this could trigger significant tax obligations (the tax basis in raised grain and livestock for Schedule F tax-filers is zero, so the full proceeds at sale are taxed as ordinary income) which reduces the liquidity position even further.

An alternative lender response is to restructure the debt and move some of the current obligations to non-current using the appreciated value of farmland as security. This approach in essence results in leveraging the capital gain in farmland – the leverage effect of capital gains as discussed earlier. Lenders who may have previously resisted increasing loan to value ratios on farmland purchases to limit increased debt utilization by farmers paying higher and higher prices for farmland will now be encouraged to monetize capital gains in land by extending additional credit based on the higher land values. Higher land values and resulting increased equity positions would appear to provide adequate security and secondary repayment capacity to support the larger debt load, but the debt per dollar of revenue generated from the land will be higher if the income shock is permanent rather than temporary. The business is now very vulnerable to further income shocks or asset value deterioration — the working capital position has been destroyed and credit reserves have been fully used. Permanently lower incomes and/or higher interest rates will not only create debt servicing problems, but also reduce the discounted cash flow and thus weaken the demand for farmland. If debt servicing problems result in forfeitures or foreclosures in the farmland market, additional properties are likely to be offered to the market, and weakening demand and increased offerings (or forced sales) are likely to result in reduced farmland values.

Livestock producers may be even more vulnerable to income shocks than grain farmers. The significant losses suffered by both pork and dairy farmers in particular during the 2007-2009 period, substantially reduced the equity and working capital positions of many of these businesses. Some producers covered these losses with increased operating or term debt, thus increasing their leverage positions. Although profits improved significantly in 2010 and 2011, they have not been sufficient to rebuild equity and working capital positions. And asset values for specialized livestock facilities and breeding stock declined dramatically during the period of large losses, resulting in further deterioration of solvency and secondary repayment positions. These values have recovered only modestly from those distressed levels, so many livestock producers are very vulnerable to not meet lender liquidity/working capital as well as solvency underwriting standards even with modest price reductions or cost increases.

So What?

The sequence of events just described characterized the 1970’s-80s for the U.S. farming sector, resulting in a strong boom and a dramatic bust in financial performance and land values. Today we appear to be in the mid to late stages of the boom – incomes are moderating and the wealth effect as a driver of land purchases remains muted. If incomes strengthen and/or the “wealth effect” becomes stronger (or both), land prices could continue to rise rapidly resulting eventually in liquidity and working capital problems if/when income shocks occur. Even though lenders may be conservative in their credit policies, liquidity/working capital pressures could result in increased refinancing of land debt — the leverage effect. The end result would be a bust much like the 1980’s. Mitigating this end result requires continued muting of the wealth effect, maintaining or rebuilding the working capital of farm businesses and preempting the leverage effect.

TAGS:

TEAM LINKS:

RELATED RESOURCES

Margaret Lippsmeyer presented during agri benchmark’s 2024 annual conference in mid June, which was hosted by the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture in Valladolid, Spain. An increase in soybean acreage may come from either (a) shifting away from continuous corn rotations to corn-soy and (b) shifting corn-soy rotations toward corn-soy-soy. Based on agri benchmark data, Margaret showed that option (a) would require an increase in soybean prices of 6% and option (b) of 8% to make these rotations preferable over existing ones.

READ MOREUPCOMING EVENTS

We are taking a short break, but please plan to join us at one of our future programs that is a little farther in the future.