February 8, 2013

Beef Cow Rental Arrangements for Your Farm

Managing risk is required for many farm enterprises to be profitable and sustainable. Leasing assets, rather than purchasing them, is a form of risk management as it typically requires less capital. Leasing or sharing arrangements between farm operators and property owners have long been used to acquire control of land. In recent years, leasing has become more common for machinery and livestock. Contractual arrangements — such as livestock leases — can be crafted to lend or transfer capital, while also sharing risk. The terms of the agreement depend on the contributions of the owner and operator, as well as the motivation for the lease. A lease agreement may be part of a plan to transfer livestock ownership to a second generation, the means for an older owner to compensate a livestock operator, or simply an alternative form of accessing capital. A pasture owner may also use a livestock lease agreement to generate income without committing labor or additional capital.

Through share lease arrangements, the livestock owner typically shares the production risks, expenses, and returns with an operator. While the owners may give up some of the risk, they may also give up some of the decision-making power. In developing a lease, owners and operators generally want an arrangement that is equitable to both parties. For a successful relationship between the owner and operator, the following elements should be present:

- The owner and operator must be willing to risk some capital.

- The owner and operator should have mutual trust and confidence in each other.

- The operator must convince the owner that he or she has the managerial ability, honesty, and integrity to capably manage the livestock enterprise.

- The operator must be confident that the owner will deal fairly and honor the contract arrangements for shared returns.

The cow owner may want to check references of the operator, and the operator may want to investigate the owner’s reputation to assess if this is somebody they want to do business with. The owner should compare the return on investment in livestock, fences, and buildings with alternative investments to make an informed decision relative to business and personal goals.

A key principal to remember when developing a cow herd lease is to KEEP IT SIMPLE! It is recommended that a beef cow lease only involve the beef cows and bulls. While the leasing of other items such as pasture, hay land, and machinery can be part of a cowherd lease, leasing them in a separate agreement provides better flexibility to deal with changing conditions over time. The time and effort spent developing a simple, straight forward, and equitable arrangement in the beginning will be rewarded with better relations between owner and operator and a more efficient beef-cow enterprise.

Livestock Lease Terms

The owner and operator should communicate clearly their expectations for the arrangement. The lease should be a written contract which is agreed upon by both parties and should note for instance whether or not a partnership is intended as there are legal implications. A sample lease form accompanies this publication (NCFMEC-6A). The arrangement can be simple, but it should cover all the important points. The agreement should include the names and addresses of participants, and it should answer the following questions:

- When does the agreement start? How long does it run?

- Is it automatically renewable? Note that while an automatic renewal may seem appealing, it should not substitute for ongoing communication between parties.

- When and how is termination notice given? What are grounds for termination?

- When will the agreement be annually reviewed?

- Which party provides for and pays for feed, water, care, veterinary services and medicine, fencing, etc. and what share does each provide? Fencing may not be an issue if pasture is leased separately but it should be discussed so all parties know their obligations.

- What is the share of the output for each party? How are calves priced if one party buys calves from the other?

- When and where is the share of output divided?

- How are cull animals disposed of and when does culling occur? Who receives the income from culls?

- Who provides replacement breeding livestock? Is there a separate agreement for growing replacement heifers?

- What determines the acceptable amount of death loss for each party? How is death loss documented?

- Who provides bulls? What type and quality of bulls (or semen) are used?

- Are cows insured? Who carries the insurance?

- What facilities are used?• Are there special requirements/needs regarding feeding/handling of cows or calves?

- Are incentives provided for doing a “good” job? Are penalties assessed for doing a “poor” job?

- What records are kept? How are animals identified?

- How are extenuating circumstances (such as drought, blizzard, or major health problems) that are not the fault of the operator handled?

- What limits, if any, are placed on the activities of the operator? For example, can the operator add other cattle to the owner’s herd?

- How are disagreements settled? Is there a way for either party to get out of the agreement?

- If the owner terminates the agreement prior to the agreed-upon end point, how is the operator compensated for expenses up to the date that the cows are removed from the producer’s premises?

If land is part of the agreement, these additional questions should be addressed:

- How many acres of land and what type of pastures and crops are included? (Include legal descriptions, if possible.)

- What is the expected stocking rate?

- Who is responsible for pasture maintenance and upkeep expenses (e.g., fences, noxious weed control, water systems)?

- Are improvements needed in buildings or facilities? If so, who will pay for them?

Share versus Cash Lease Agreements

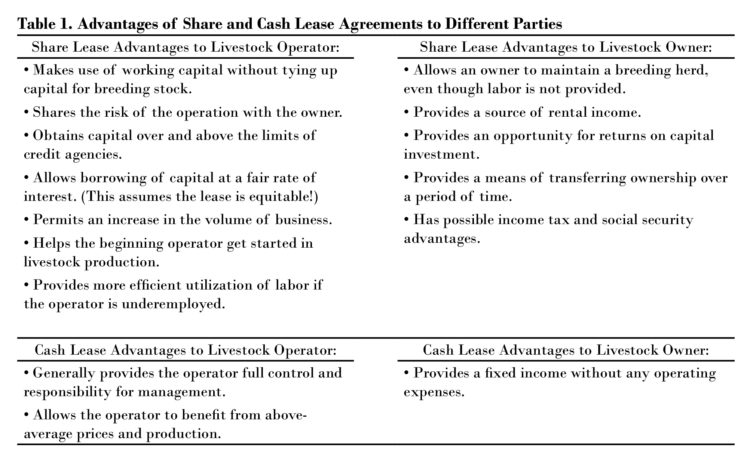

Leasing beef cows on a share basis can have advantages for both parties (see Table 1). Some of the factors that need to be determined for a share-leasing arrangement to be equitable are:

- Costs to be included.

- Cost of resources contributed by each party and costs to be shared.

- Percent of costs contributed by each party.

- Quality of cattle furnished.

- Methods for valuing inputs and products.

- How death losses or other adverse outcomes will be shared.

As a rule, share arrangements are considered equitable for the parties involved if the value of the shares received (i.e., income) reflects a similar share of the value of contributions made (i.e., costs). That is, income is shared in the same proportion as costs are contributed. It is best if an owner and operator can work together in determining their respective contributions. They might work independently at first, then meet to share their estimates and negotiate final terms of the agreement.

Cash leasing is common with pasture, less so for crop ground and less yet for livestock. However, some people may want to consider a livestock cash lease. For the cash lease, the cow owner furnishes a set of bred cows and/or heifers and possibly bulls to the operator for a set period of time for a predetermined lease price. The operator receives the livestock, cares for and manages them, keeps the calf crop, and returns the cows to the owner at the end of the lease. The lease may be for one or more years. In a multi-year agreement, the cow owner is responsible for providing replacement cows, or the leased herd could become smaller and smaller over the years from death loss and cull sales. A cattle owner wanting to exit the business typically will not provide replacement cows; rather the operator will provide replacements and thus over time the ownership of the herd will transition between the two parties.

Additional details need to be agreed upon before a lease is signed. Some of these are the condition of the cows when returned, breeding program to be followed, death loss allowed, and vaccination program/veterinary cost for the cows. If the lease is for one year only, the cow owner would typically furnish the bull(s) because the operator would not have any benefit from the next year’s calf crop. If the lease is for more than one year, the operator is more likely to provide the bull(s) to control the genetics of the next calf crop.

Table 1 highlights some of the advantages to the livestock operator and owner of the different types of leases. Tax considerations may also play a role. If the cow owner leases the cows and receives a base cash rate, he or she will not be subject to self-employment tax on that income. However, a cow owner who shares a portion of the production risk will be subject to self-employment tax on the income received. Production risk occurs if the owner’s returns are a portion of the calf crop or if the owner shares a role in the management of the cow herd. The IRS defines the management role as material participation and considers the cow owner to have “materially participated” if:

- The producer does any three of the following activities:

- Inspects production activities (e.g., calving or feeding). Inspecting property or improvements does not count.

- Consults with the operator about production of the cow enterprise.

- Furnishes at least half (maybe less under some circumstances) of the tools, equipment, and livestock used in the enterprise.

- Shares at least half (maybe less under some circumstances) of the production expenses.

- The cow owner regularly and frequently makes decisions that significantly affect the success of the farm operation.

- The cow owner works at least 100 hours spread over five or more weeks on activities connected to the cow enterprise.

- Even if the cow owner does not meet 1, 2, or 3, when considered together, his or her activities may be enough for a ruling of material participation.

Because material participation is somewhat difficult to define, the cow owner should consult with a tax advisor if tax consequences are important for their situation.

Developing Equitable Share Arrangements

Generally, the percent of profits each party receives is based on his/her contributions to the enterprise. If the income is divided in a way that does not match each party’s contribution to the enterprise, for instance, in a generational transfer of assets, it is essential that the owner and operator agree upon the terms. Because of the differences in individual farms and items furnished, the contributions in these arrangements may appear similar when, in reality, they may vary a great deal. Some of the differences may include one or more of the following:

- Quality of cattle furnished. A party who furnishes $3,000 cows contributes twice as much per cow as one who furnishes $1,500 cows. Selling a 6-month-old bull calf for $2,000 contributes much more to the receipts than selling a steer for $1,000.

- Labor. A party who furnishes the labor for growing all the feed and providing the temporary pasture furnishes much more than one who just feeds protein supplements to a cowherd. This can be accounted for by valuing contributed raised feed at market value. The labor requirements on timber pasture are higher than open pasture.

- Pasture.The value per acre of pasture varies widely. What is important is the pasture cost per cow (which also can vary).

- Machinery and equipment.The value of

the machinery and equipment depends on the acres of hay and pasture produced, the amount of roughage harvested and transported, and the quality of handling facilities contributed. As with feed, if hay is valued at market price, it presumably covers cost of production, including machinery and equipment costs as well as labor and management. Machinery costs for feeding cattle can also vary considerably based upon type of feed, number of cows fed with equipment, and age/quality (i.e., value) of equipment.

Some production expenses, such as veterinary care and drugs, may be shared. Because these costs affect cash flow and profitability analyses, they should still be considered in the overall analysis of enterprise profitability (even though they do not affect the relative contributions of either party when shared in the same proportion as income).

The leasing agreement should be evaluated occasionally to assure an equitable arrangement over time. Fluctuating prices can cause the proportion of contributions to shift. This could be caused by changes in interest rates, feed costs, value of breeding stock, or labor and management costs.

An infinite number of possible arrangements for sharing the income generated from the contributions of livestock, land, and the other resources are possible. Therefore, it is important that both parties itemize their contributions and the expected values associated with those contributions.

Determining Costs to be Included

Actual farm records are an excellent place to start when determining the basic input items and costs that should be considered when developing a beef-cow lease. Standard budget worksheets (Worksheet 1) or computer programs can be used to help identify relevant costs and organize the costs for the required calculations. Many state Extension services offer budgets that may serve as a resource (see http://www.agrisk.umn.edu/Budgets/ for links to many state sites). Standardized Performance Analyses summaries offer benchmarks for production as well, particularly representing the southern Plains states (http://agrisk.tamu.edu/agrisk/beef_cow_calf/index.php). These are especially helpful when working out a lease agreement for the first time.

Cow herd costs can be calculated either for the whole herd or on a per cow basis. Total herd figures are sometimes easier to obtain from farm records, but the parties must be sure cost items are based on the same number of cows as will be in the lease. For this reason, it is often recommended that costs be calculated on a per cow unit basis. A cow unit is the cow, her calf, her share of the bull, and her share of a replacement heifer when replacements are raised within the lease. For example, if there are 100 cows in the herd and both the owner and operator agree that 15 heifers need to be retained each year, then the development costs for the heifers should be entered into the cow unit-cost budget, where the per-heifer cost is multiplied by 15% (i.e., 15 heifers divided by 100 cows). Likewise, the costs associated with bull ownership and care should be adjusted by the bull-to-cow ratio.

Estimates of annual fixed costs for assets such as breeding stock, buildings, machinery and equipment can be approximated using the following steps:

Average investment = (original cost + salvage value) ÷ 2

Annual depreciation = (original cost – salvage value) ÷ years of useful life

Annual interest = average investment × interest rate

Annual insurance = average investment × insurance rate

Annual taxes = average investment × personal property tax rate.

Note that depreciation is not based on tax depreciation as tax laws change over time and often allow complete “expensing” of items. Used machinery or equipment would have a shorter useful life than new items. In some cases it may be more appropriate to use a replacement cost or current market value as opposed to original cost in the above formulas. What is important is that the useful life is consistent with the value used. For example, the useful life of a new building will be much longer than one associated with an older building.

A short explanation of each cost item listed in Worksheet 1 may help in arriving at an equitable arrangement.

Livestock Ownership

Interest on the average value of cows represents the investment contribution of the owner. The interest rate used should be between the rate that could be earned if money were invested in other alternatives (opportunity cost) and the current rate for borrowed capital.

Depreciation on cows is a contribution of the owner if he/she is responsible for purchasing or raising the replacements outside of the lease. Total depreciation is the difference between the market value of the cow when she is placed in the herd and her salvage or cull value when she is removed from the herd. To arrive at the annual depreciation, total depreciation is divided by the number of years the cow is expected to remain in the herd. When replacement heifers are raised within the lease, these costs are included in the production inputs so depreciation is not a factor.

Interest and depreciation on bulls are computed in the same way as for cows. The annual cost of the bull is divided by the number of cows served each year to determine the cost to be allocated against each cow. Schedule A can be used to estimate the depreciation and average investment for both cows and bulls.

Taxes on livestock are the amount of personal property tax (if any) on the cows and bulls.

Cow insurance or death loss could be shared if, for example, the operator guarantees a maximum death loss. The cost of insuring the cow is typically used, but death loss can

be substituted when the contributing party “self insures” (i.e., does not buy insurance). Do not include both if death loss is reimbursed by insurance. Cow insurance or death loss is usually computed at 0.5 to 1.0 percent of the average value of the cow.

Machinery, Equipment and Buildings Used in the Livestock Enterprise

Interest and depreciation on buildings, machinery and equipment used in the livestock operation is a contribution of the party who owns the property. One alternative for valuing the contribution is to use the rental rate (for example, cost per hour to rent a tractor), which may work well where markets are established and rental rate information is available. In other cases, it may be appropriate or necessary to calculate annual interest, economic depreciation, interest and taxes on the contributed assets. Assigning a proportion of the value of an asset to the livestock enterprise is also required, if for instance, a tractor or trailer is used for other purposes in addition to the cow enterprise.

The value of buildings, machinery and equipment used in the beef-cow enterprise varies from operation to operation.

Schedules B and C can be used to estimate the machinery, equipment and building investment used in livestock production. Livestock machinery and equipment would include tractors, wagons, trucks, trailers, loaders, manure spreaders, big bale spears, hay feeders, feed bunks, mineral feeders, and handling facilities used in feeding, handling, and observing livestock. Livestock machinery and equipment does not include hay or silage harvesting equipment if crop/hay contributions are valued using market prices.

Taxes and insurance on buildings and equipment are the costs for taxes and insurance incurred against property used for livestock during the year. These costs typically range from 1 to 2 percent of the current value of buildings and equipment.

Repairs on buildings and equipment are the costs of maintaining buildings, equipment, and fences used for livestock production. Repairs typically average 2.5 to 4 percent of new costs on an annual basis.

Pasture

The land charge for pasture can be calculated two ways: a) landowner’s ownership costs or b) cash rental value. Ownership costs include a return on land investment plus real estate taxes. The cost of fencing, gates and watering systems may be included in the land investment when being used in

the livestock enterprise. A fair market value for agricultural purposes is placed on the land and multiplied by the long-range rate of return to land (typically 1 to 4 percent)

to calculate the annual contribution. Real estate taxes are actual costs; however, they may be accounted for in the rate of return and thus it is important to not double count them. The rental value for the landowner is the amount for which the property could be rented to someone else. If the land is being rented by the party providing it, then the contribution is the actual cost of rent. Rental rates may be quicker and easier to use if there is an established market for pasture in the area. Schedule D can be used to calculate the number of acres of pasture needed per cow unit. For more information on pasture leases, see NCFMEC-03, “Pasture Rental Arrangements for Your Farm”.

Feed and Other Expenses

Software tools may be useful in determining appropriate combinations

of forage, hay and feed to meet the cow’s nutritional needs under different pasture situations and feed/hay pricing environments (for example, see http://beefextension.com/files/Cowculator%202%200.xls). Hay, silage, and other raised feed should be valued at long-run market prices when estimating contributions for a multiple year lease. However, if the lease will only be for one year then it may be more appropriate to use current market prices. Market value is the price that could be received if the product is sold instead of used on the farm. Cost of production can be used in a whole farm lease agreement; however, market values are generally used because they are simpler to calculate. It is recommended that long-run market values be used for all raised feed for the beef cow herd share agreement. NOTE: If hay, silage, and/ or grain raised under a separate crop-share lease arrangement is fed, the landowner needs to receive credit for his or her share. If both parties contribute to the cost of producing feed, each party should receive credit for his or her contribution. For example, one party may furnish land for hay production and the other party may furnish machinery and labor. However, as stated previously, the cow herd lease arrangement will be much more straightforward with fewer potential complications if other leased assets (e.g., pasture, hay ground, crop land) are handled with a separate agreement.

Protein and mineral supplements should be valued at cost. It is generally recommended that protein and mineral be furnished by the same party providing the hay and forage so there will be no conflict concerning winter rations.

Veterinary and drug expenses may be contributed by either party, or they may

be shared the same as the income is shared. When shared the same as income, they are not factored into calculations for determining the equitable shares. (See section on shared and unexpected expenses.)

Fuel and oil costs would be for feeding, hauling, and observing livestock.

Truck expenses, including repairs, license, insurance, interest, and depreciation, should be prorated to the cow herd if the truck is not included in the livestock machinery and equipment. Hired trucking and marketing generally are shared, because they are often deducted from sales.

Utilities and miscellaneous costs should include water charges, electricity, telephone, postage, dues, and registration fees that are chargeable to the cow herd.

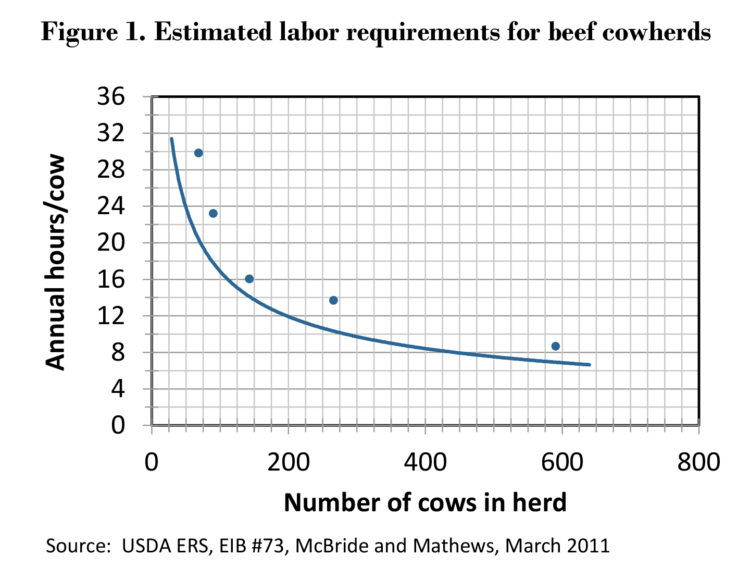

Labor is a contribution of the party providing it. If labor is hired, the expense is the actual cost to the party who pays for it. If labor is furnished by one or both parties, then labor should be valued at the going rate as though it had been hired. Labor required per cow per year will vary with the size of the herd. Large herds will require around 6 hours per cow per year while per cow requirements for smaller herds may be substantially higher (see Figure 1). An additional allowance would be required if replacements are raised within the lease rather than purchased.

Management of the cow herd typically will be the responsibility of both parties. The owner of the cows should decide, in consultation with the operator, which

cows to cull and which heifers to keep for replacements. The owner, along with the operator, should decide on bulls to use that will maintain or improve the herd quality.

The operator should be responsible for the day-to-day decisions involved in managing

the cow herd to produce maximum returns. Management can be valued at 0.5 to 1.0 percent of capital managed or 5 to 10 percent of value of annual production. Schedule E can be used to calculate a management charge. Because management is difficult to define, and because both parties provide management, this contribution is often excluded from the calculations in determining equitable shares.

Shared and Unexpected Expenses

Sharing the cost of production-increasing inputs in the same percentage as the value

of production encourages the parties to use the optimal amount of the input so as to maximize net returns to the total business operation. Examples of production increasing expenses include, but are not limited to, antibiotics, implants, and creep feed. Even though shared expenses do not affect relative contributions, they should be calculated for a total cost estimate that can

be used for cash flow and profitability analysis. These costs can be entered on Worksheet 1.

Unexpected expenses such as additional feed during a blizzard or drought, catastrophic health problems, and other irregular items should be shared, because they are periodic and hard

to predict. If shared, unexpected expenses do not change the percent contribution of either party when they occur.

Total Costs

Total costs reflect the combined contributions of both parties. The number may lead to concern by lease parties about the profitability of the cow herd operation, which is a risk each party assumes. If gross returns per cow exceed total costs per cow, each party will get full value for all costs plus a “profit.” If gross returns are less than total costs, then each party will not receive full value for their contribution. However, this does not necessarily mean that each party does not benefit from the operation. Livestock owners may realize benefits such as capital gain advantages and pride of ownership. Livestock operators may be able to use hard-to-market feed and off-season labor.

Determining Contributions of Each Party and Percent Contributed

After the annual contribution for all production inputs is determined (Worksheet 1, total column), costs are allocated to the party who contributes each particular input (owner and operator columns). If a certain input factor is provided by both parties, it is divided between them. Worksheet 1 can be expanded to include more than two parties if needed. As noted earlier, the value of homegrown grains and forages raised on land owned by one party and farmed by the other party are prorated based on the crop-share agreement. When the allocations are completed, the inputs are added to determine the total contribution by each party.

To determine the percent contributed by each party, divide the amount contributed for each individual party by the total contribution of all parties. Expenses to be shared should be shared in these same percentages.

Determining Income

Value of production is shared in the same proportion as costs are contributed. Value

of production may or may not be the same as sales. When replacement heifers or cows are purchased or provided from other sources outside the lease, value of production equals total calf sales. Calf sales are shared based on the percent contribution. However, when replacement heifers are retained and not sold, their estimated value plus calf sales equals value of production. Total value of production is shared based on the percent contribution.

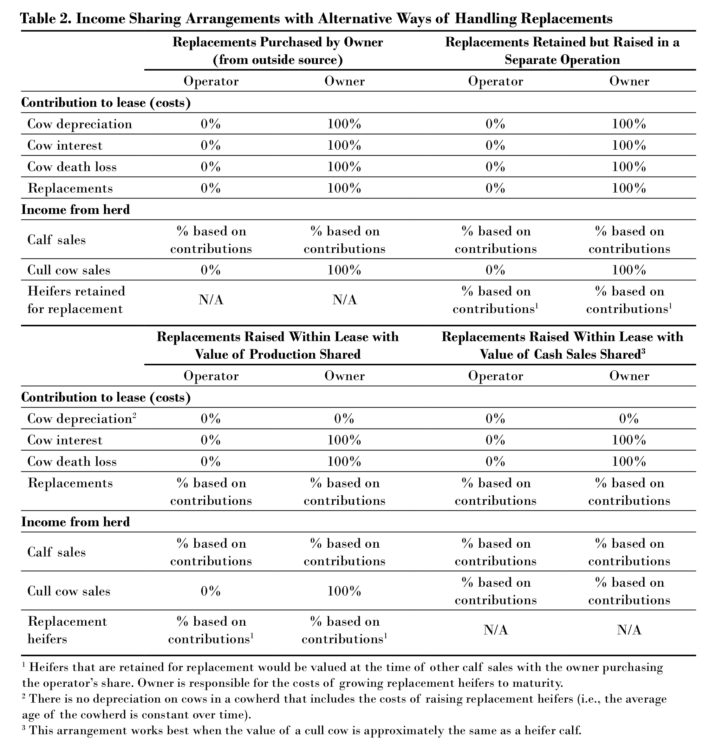

The method of providing replacement cows or heifers has a major impact on items that are considered as contributions and on how cash income is shared. In all cases, cull bull income would go to the party that provided the bull(s). When replacement females are provided by the owner and not raised as part of the lease, depreciation and death loss are part of the owner’s contribution; when replacements are raised as part of the lease, depreciation and death loss are not

part of the owner’s contributions, leading to a smaller share of contributions unless other adjustments are made. Table 2 highlights several ways of calculating contributions and sharing income for alternative ways of how replacements are handled in the lease (also described in more detail in notes that follow).

- Replacements are purchased by the owner. All calves are sold and proceeds are split based on contributions. Cull cow sales go to the owner and the owner provides replacements. This is the simplest and most clear-cut method.

- Replacements are kept but raised in a separate operation. A market value is placed on the replacement heifers as if they were sold. When the remaining calves are sold, 1) the operator and owner share all calf sales, and the owner purchases the operator’s share of the replacement heifers; or 2) the operator receives a higher percentage of cash sales because the cow owner receives the replacement heifers as a share of income. In either case, the operator’s income equals operator percentage share times the sum

of cash sales and the value of replacement heifers. The cow owner would receive all cull cow income, would own the replacement heifers, and be responsible for the cost of growing them to maturity. - Share value of production of calves (calf sales plus value of replacement heifers). This method is the same as method 2 except the cow owner’s share of contribution and receipts would be smaller. Owner’s cost would be lower because the cost of growing the replacement heifers is included in contributions. The cow owner would own the replacement heifers and would receive all cull cow sales.

- Share all sales. All calf and cull cow sales would be shared based on percent contribution. Cow sales are substituted for the value of replacement heifers. This method is simpler and works well when cull cows are about equal in value to heifers and the size of the herd stays the same. The owner has less capital gain sales and more ordinary income for tax purposes.

A beef-cow share-leasing arrangement that is fair, equitable, and simple can

be very satisfactory for all parties. The worksheets in this bulletin and supporting schedules can be used to determine the value of contributions and percentages for sharing income. A companion computer spreadsheet (KSU-BeefCowLease.xls) is also available that can be used to estimate the equitable share rent and cash rents. The Excel spreadsheet is available at www.AgManager.info/Tools/ default.asp#LIVESTOCK or the AgLease101. org website. (A similar tool, File C2-36, is available on the Ag Decision Maker website)

Cash Leasing Beef Cows

Under certain conditions, renting cows for cash might be preferable to a share arrangement. For example, a farmer/rancher contemplating retirement might be interested in renting out his or her cows. A young

farmer, limited on capital, might be interested in renting extra cows to utilize pasture. In either case, neither party may be interested in renting for long periods of time. The same information used to determine the value of contributions under a share arrangement is used to determine cash rent desired and an ability to pay rent. Compensation is expected for a return on investment, depreciation, taxes, and death losses. The prospective renter should estimate the returns from a cow (or herd) to determine how much rent could be paid.

Determining the Cash Rental Rate

Cash rental rates can be determined three ways:

- Livestock ownership costs. Ownership costs are the same as discussed in the share lease section. They are depreciation, interest on investment, insurance or death loss, and personal property taxes, if any. Section 2 of Worksheet 2 can be used to calculate ownership costs.

- Livestock owner net share rent. Net share rent for the livestock owner is the owner’s share of value of production less shared expenses and a risk adjustment. The net share rent is adjusted for risk because the owner no longer has any production or price risk (Worksheet 2, Section 2).

- Operator’s net return to livestock. Operator’s net return to livestock is the value of production minus the operator’s production expenses. The net return to livestock represents the most an operator could pay given the estimated costs. Worksheet 2, Section 3, can be used to calculate the operator’s costs and net return to livestock.

Evaluation of the three rates can provide an opportunity for discussion and negotiation to determine an acceptable cash rental rate.

Cash rental rates need to be reevaluated on a regular basis. Cattle prices can change significantly from year to year, changing the return to fixed assets. Because risk is not shared between owner and operator, the lease may need to be re-evaluated or changed to a share arrangement.

Leasing Bulls

Another way for the cow owner to reduce expenses is to lease, rather than own, a bull. The producer must compare the costs and benefits of leasing a bull with owning a bull. Leasing eliminates the capital expenditure of purchasing a bull. The cost of purchasing a bull depends on the cattle market and quality of the bull. Most bull owners in the leasing business charge $700 or more per breeding season.

A leased bull is generally only kept during the breeding season, so operating costs are reduced. For example, the cost of feeding a bull is estimated at $350 per year. The costs

of veterinary and medicine, marketing, and death loss (1 percent) approximate $35. Labor is estimated at about $45 per year, resulting in total cash costs of $430 per bull per year.

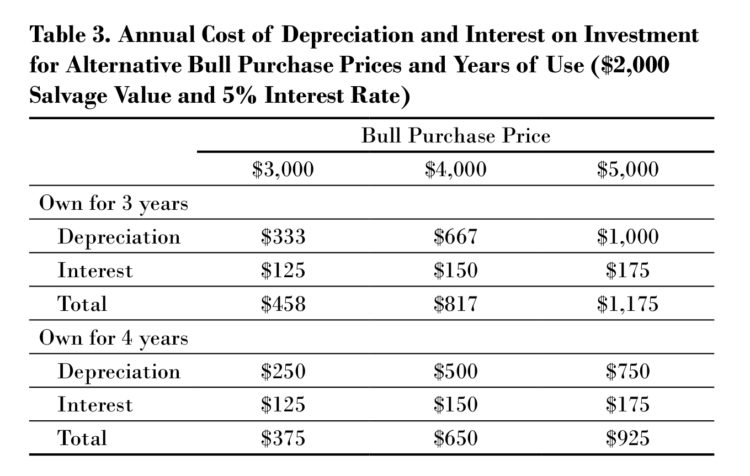

Another cost of owning a bull is depreciation and interest. Table 3 gives an example of the costs of depreciation and interest on average investment for a bull depreciated for three and four years using a 5% interest rate and $2,000 salvage value with different purchase prices.

Table 3. Annual Cost of Depreciation and Interest on Investment for Alternative Bull Purchase Prices and Years of Use ($2,000 Salvage Value and 5% Interest Rate)

The cow owner must also consider how leasing a bull could affect the health of their herd. Leasing virgin bulls is ideal to ensure that a venereal disease such as vibriosis or trichomoniasis is not introduced into the herd. This may not be an option, so owners should consult a veterinarian to ensure that leased bulls are healthy.

If they have adequate capital and a large cowherd over which to spread operating costs, producers may want to own one or more bulls to ensure they have a quality bull for use each season. There is also the benefit of the salvage value when the bull is sold.

Putting the Agreement in Writing

A written agreement offers a number of advantages:

- It encourages a detailed statement of the agreement that assures a better understanding by both parties.

- It serves as a reminder of the terms originally agreed upon.

- It provides a valuable guide for the heirs if either the operator or livestock owner dies. The agreement should be carefully reviewed each year to ensure the terms of the agreement are still applicable and desirable.

- It serves as documentation for tax purposes.

Every lease should include certain items. These are the names of the parties involved, an accurate description of the property being rented, the livestock lease terms described earlier and the signatures of the parties. Absent a statutory or constitutional limitation, the duration of the lease can be any length of time agreed upon by the parties. Most leases are for at least one full year. Operators sometimes request leases for more than one year, particularly if they must invest more capital in equipment or improvements needed.

The lease also needs to clearly specify ownership of the cattle. Sometimes, a lessee may have a loan secured by his or her cattle. However, the definitions of “cattle” in the loan documents may be so broad as to include all cattle possessed by the rancher. As a result, the owner of leased cattle runs the risk of his or her cattle being seized and sold if the lessee defaults on his or her loan obligations. To minimize this risk, the lease document needs to be very clear that (1) title to the leased cattle remains with the lessor, (2) the lessee will take whatever steps are necessary to prevent the leased cattle from becoming “collateral” for any of the lessee’s debts, (3) the lessee will reimburse the lessor in the event of any seizure and sale of the lessor’s cattle, and (4) the lessee will not brand, mark, or identify the leased cattle in any way that could cause them to be mistaken for the lessee’s own cattle. The lessor should also take care to brand, tag, or otherwise identify the cattle with his or her own marks before turning over possession of the cattle to minimize these risks.

In general, most transactions involving real estate require a contract in writing to be enforceable. In most states, oral leases for not more than a year are enforceable. Because specific legal terms surrounding leasing vary from state to state, livestock owners and operators are encouraged to check with their local Extension service or a knowledgeable lawyer as to the specific laws for their state. As a practical matter, though, it is always a good idea to put the agreement in writing, regardless of its duration. Putting an agreement in writing helps both parties understand their rights and duties and can help resolve many disagreements before they even start.

Livestock owners, as well as operators, should enter long-term leases only after very careful consideration — a lease contract “marries” parties to undesirable and desirable provisions alike. Often, it is better to include a provision for buy-out terms or compensation for unexhausted improvements made by one party rather than to have a long-term lease that fixes terms for an extended time period. One of the functions of a written lease is to anticipate possible developments and to state how to handle such problems if they actually do develop.

Conclusion

A cow share lease is a prime way for a cow owner and operator to pool their land and livestock resources. If the arrangement is properly laid out ahead of time, the lease can help each party share production risk. The lease should be a written document and cover all costs of production as well as possible situations that could arise during the duration of the contract. The parties entering into the arrangement should clearly define their expectations with respect to sharing of costs and receipts. The cow owner and operator should choose an arrangement that best matches their resources and desired returns.

Worksheets

* Originally published on Ag Lease 101 by North Central Farm Management Extension Committee. http://www.aglease101.org.

TAGS:

TEAM LINKS:

RELATED RESOURCES

UPCOMING EVENTS

We are taking a short break, but please plan to join us at one of our future programs that is a little farther in the future.