February 8, 2013

Rental Agreements for Farm Buildings and Livestock Facilities

Farm buildings and livestock facilities often outlast their owner’s need for them, but are still usable. Other operators want the services of certain types of farm buildings but are not in a position to invest in new facilities. Both parties can benefit by developing a lease arrangement. The owner receives a return from resources that might otherwise lie idle or be underutilized. The operator can use these resources without making a large fixed investment. However, they must agree on the amount of the rental payment and the use and care of the property.

This publication examines the major considerations in developing rental agreements for crop and livestock buildings and facilities from both the owner’s and operator’s points of view. Three different approaches to determining a cash rental rate will be presented. Finally, several other important considerations for developing a lease agreement will be discussed. A sample lease form is also included.

Value of the Facilities to the Operator

The operator should carefully budget the added net income that could reasonably be expected from using the building or facility. This provides an estimate of how much the operator can afford to pay for the use of the facilities.

An operator should consider several key factors before entering into a rental agreement:

Condition–Are the building and equipment in usable condition? Will major repairs be needed? Who will pay for repairs and maintenance? Will operating costs be unusually high? Poor feed storage may result in high spoilage, or livestock performance may suffer if equipment breaks down.

Obsolescence–Does the facility reflect current technology? Can replacement parts be easily obtained? Does it meet current environmental regulations? Extra labor, management and supervision may be required with outdated equipment.

Use−Does the building or equipment fit the operator’s current needs? A hog producer may have little use for a silo or milking parlor.

Size–Are the buildings and equipment of large enough capacity for profitable livestock production, considering the operator’s labor and feed supplies? Is the storage facility large enough for the quantity of grain, forage or machinery to be stored? Or is it too large to be used efficiently or to match the operator’s other equipment?

Location–How far are facilities located from the operator’s base of operations? Distant buildings are less valuable to the operator because of the higher transportation costs and greater inconvenience involved. Security risks are higher if livestock, machinery or stored crops are located where they cannot be regularly observed.

Convenience–Is the operation of equipment simple and efficient? Can grain or livestock be easily unloaded and loaded? Does the building contain features which increase operator safety or comfort? Or, is it of a design that poses physical risk to the operator and livestock?

Alternatives–Could the same services or facilities be obtained elsewhere? At what cost? If the owner is offering a service that is difficult to obtain in the area, a higher rental rate will likely result. Likewise, the number of other people who might want to rent the same building will impact its rental value.

Establishing a Rental Rate

Most owners and operators want to determine a fair and reasonable rental rate given the particular circumstances of their situation. However, a common or typical rental rate for a particular building or piece of equipment seldom exists. In many areas there is no widespread market for specialized livestock buildings. The fixed location of existing structures often narrows the market to just a few prospective operators. The factors surrounding each individual case and the bargaining position of each of the parties involved will determine the final rental rate.

Owner’s Costs

Owners are primarily interested in recovering their costs for a particular farm building or facility, particularly any operating costs not paid directly by the operator. In addition, owners may consider proper care and maintenance of their property to be important. At a minimum the rental rate should cover any added costs related to the use of the facility. These variable costs include use-related repair and maintenance costs, utilities expense and additional wear and tear.

Most of the owner’s costs will remain the same regardless of how much the asset is used. These costs are usually called ownership or fixed costs, and include depreciation due to age, interest (return on investment), property taxes, insurance and certain repair and maintenance costs not related to use. Because these costs occur whether the asset is rented or not, any rental amount in excess of variable costs is a net gain to the owner, even if it pays only part of the ownership costs.

Estimating the total of the owner’s costs for the item rented can provide a starting point for negotiating a rental rate. Worksheet 1 can be used to help estimate these costs. Following is a brief discussion of some of the factors impacting the owner’s costs.

Current Value–Most ownership costs can be tied to the current value of a building or facility.

The best estimate of the current value of buildings or equipment is the price that could be realized from selling them on the open market. However, some items are not sold frequently enough to have an established market price.

Original cost is not a very good estimate of the current value of buildings and equipment unless they are only a few years old, or are being newly constructed. Current value is usually less than the original cost due to depreciation and obsolescence. Current replacement cost is a good place to begin when estimating the current value of a facility. Replacement cost refers to the cost of a new implement or facility which is of similar size as the one in question, performs a similar service and is technologically comparable. Estimating current value as a fraction of today’s replacement cost adjusts for both depreciation and inflation since the asset was new.

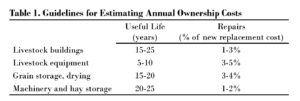

For example, a livestock shed that has an estimated useful life of 20 years (Table 1) and which is now eight years old would have an estimated current value equal to 60 percent of its replacement cost (12 years remaining divided by 20-year life). If the lease period will be more than one year in length, use the average age of the property during the expected lease period, rather than its current age.

If the property is in particularly good or poor condition for its age, or functionally obsolete, adjust the current value up or down to reflect this.

Some facilities have very specialized uses or are attached to a fixed location. This often reduces their market value and rental value. A realistic estimate of current value should take this into account. Unusually complex or expensive facilities should be valued by a professional appraiser or dealer, particularly if a long term rental agreement is being negotiated.

Depreciation–The annual depreciation for equipment or facilities depends on the remaining useful life. For example, items with a 10-year remaining life depreciate at an average rate of 10 percent of their current value annually. Remember that you are estimating loss of value due to use and obsolescence, not depreciation for income tax purposes. The full investment cost of many items can be depreciated on the tax return at a much faster rate than their useful values decline.

Facilities that have aged well beyond their original useful lives may be considered to have no depreciation expense, that is, they are no longer losing value.

Interest–The interest rate for intermediate term loans and the rate of return from other fixed investments can be used to estimate a cost of capital. Multiply this rate by the current value of the facilities, or by its average value during a multi-year lease, to find an annual interest cost.

Insurance and Taxes–The annual cost of insurance and property taxes can be estimated as one to two percent of the current or average value for most types of farm assets. If actual insurance and taxes are known, that information can be used rather than estimates. In some states agricultural personal property items are not subject to property tax. Check your own property tax rates and insurance coverage rates for accuracy.

Repairs and Maintenance–Unlike most other ownership costs, repair and maintenance costs usually increase as a building or other structure ages. Repair costs can be estimated as a percent of new replacement value, to allow for changes in the costs of parts and labor. Table 1 shows some suggested percentages for estimating repair costs for various types of rental items. For older or well-used items, use the high end of the ranges shown.

A more satisfactory method may be to keep a record of actual repair and maintenance costs incurred by the owner during the lease period. Some operators may be able to reduce repair costs by providing some or all of the necessary labor.

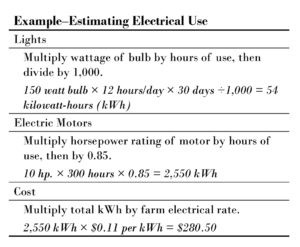

Other Operating Costs–Costs such as water, fuel and oil, electricity or gas typically will be the responsibility of the operator, either directly, or indirectly, through the overall rental charge. The most accurate method is to measure the actual consumption of fuel or other energy, perhaps through a separate meter. If electrical use cannot be metered separately, an estimate of its cost can be made based on the size of lights and motors used to power fans or conveyers involved and their hours of use (see example).

Total Costs–The total of all ownership and operating costs can be used to estimate a rental charge for the whole year or a portion of the year. If a structure or piece of equipment is rented for less than a full year, and can be rented to someone else for the rest of the year, the annual ownership cost estimates should be reduced proportionately. If the facility realistically can be rented only once a year, as in the case of a grain bin, the rent should reflect ownership costs for a full year. Alternatively, the total can be divided by a typical annual production level to estimate a charge per unit of production or use, such as the cost per pig finished.

Keep in mind that many structures may not attract sufficient rent to pay for all ownership and operating costs, due to their fixed location or a low demand for their services. However, rental rates should at least cover operating costs and added wear to make it worthwhile for the owner to enter into a lease. Thus, the operating (variable) costs is often viewed as a lower bound when negotiating rent.

When selecting or negotiating with a potential tenant, characteristics such as reliability, experience, honesty, financial condition, availability, possession of skills and equipment for making repairs or improvements, and likely longevity should be considered. A lower rental charge may be acceptable in exchange for strong performance in these other areas.

Commercial Rates

In some cases the same service being offered by the owner may be available from a commercial source at an established price. An example is storage for grain. A tenant may not be willing to pay more for grain storage than the rate at which it can be obtained at a local elevator, unless convenience is a factor. In fact, on-farm storage rates tend to be below commercial rates because the operator must assume the risk of loss, perform the labor and management functions, and use loading and unloading facilities which may be less convenient. Nevertheless commercial rates serve as an unbiased reference that reflects current costs as well as and supply and demand conditions of a close substitute or alternative for the facility being considered.

Property rental agents can help determine an appropriate rental rate for a farm home or other buildings. Additionally, commercial livestock companies often pay standard rates for the use of feeding facilities.

One advantage of using commercial custom rates as a guide to rental charges is that they reflect average per unit costs at an efficient level of use.

Farm Records

A third approach to setting a fair rental value is to find out how much it costs other farming operations to own and operate the same facilities. Many state Extension Services provide farm record summaries that have detailed cost data. If possible, use data for the same enterprise and size of operation as the facilities under consideration. Try to include all the ownership and operating costs that the owner of the facilities will pay. Keep in mind that records may not include noncash interest (opportunity) costs on the owner’s capital.

Many private production record services also provide group summaries with detailed enterprise cost data. Generally only members or users of the service have access to this information.

While record data from other farms may not accurately reflect costs for a particular set of facilities, they at least indicate typical opportunity costs for operators of not owning their own buildings and equipment.

These three approaches can provide a starting point for negotiating an acceptable rental rate. The actual rent agreed on will probably fall somewhere among these values, depending on each person’s bargaining position and the demand for and the supply of similar property in the area.

Special Considerations

Several areas of responsibility need to be discussed and agreed on before the leasing period begins. How these are handled may affect the amount of rent that is ultimately paid for the facilities.

Repairs

Most buildings and equipment will need some maintenance and repairs eventually. At the beginning of the lease the operator and owner should jointly inspect the rental property to be sure everything is in satisfactory working order. In general, it is the owner’s responsibility to have the facilities 5in good condition when the lease begins. Some leases contain a 30-day trial period at the beginning during which the owner agrees to repair any part of the facility that is not performing satisfactorily. This is especially important when equipment has not been used recently.

Next the owner and operator need to agree on how future repairs and maintenance costs will be handled. Lubrication, sharpening, adjustments to controls, and replacement of fasteners, controls and small equipment are usually the operator’s responsibility. This ensures that such repairs are done quickly, and also motivates the operator not to abuse equipment. When major building components need to be fixed or replaced, the owner generally pays the cost. The operator may provide labor and expertise to perform the repairs, when possible.

Portable items such as feeders and waterers, heaters, gates and panels, skid loaders and feed grinders can be provided by either party. Naturally the rental rate will be higher if the owner provides such items. The lease agreement should list who will supply specific items. In any case, major repair costs are usually paid by the owner of such equipment.

Some leases allow the tenant to charge repairs up to a maximum dollar amount without prior approval, but amounts over this limit must be approved by the owner before they are carried out.

Another possible lease provision is to allow a third party arbitrator to decide if major repair costs are caused by normal wear and tear, or by misuse of the buildings and equipment by the operator.

Water

An adequate supply of water is essential for livestock facilities. The source of the water and condition of pumps and waterlines should be determined at the beginning of the lease. The value of the water system should be included when estimating a fair rental rate. Repairs and maintenance can be handled as described in the previous section.

If the water supply becomes inadequate due to drought or other problems, the lease needs to state who is responsible for obtaining supplemental water. When the problem is due to natural causes, some tenants and owners divide the cost of obtaining extra water. This may include reimbursing the tenant for hauling costs. Or, the owner may pay the cost of the water while the tenant transports it.

If water is supplied by a utility, such as a rural water system, the variable cost is usually borne by the tenant. If the cost or use cannot be metered directly, some other method of estimating monthly consumption and cost must be determined.

Manure Disposal

Manure collection and disposal is becoming an increasingly important issue in livestock production. It is the owner’s responsibility to see that leased facilities meet all applicable environmental and zoning regulations related to livestock wastes.

The question of who removes manure and to whose land it is applied is best answered according to practical considerations. Who has the proper equipment and who has cropland that can utilize the manure are good places to start. Distance of cropland from the livestock facility is also a factor.

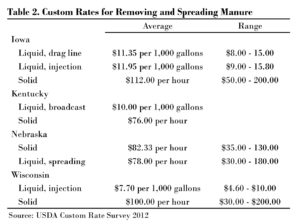

If the same party both disposes of the manure and benefits from it, then probably no payment needs to be considered. However, if the tenant applies the manure on the owner’s land, for example, then the tenant should receive payment for performing this service, or have the rental charge for the facility reduced accordingly. Times and locations for spreading must also be set. Table 2 shows some custom hire rates reported for disposing of manure.

Insurance

Generally, each party is responsible for insuring his/her own property. This means the owner would carry comprehensive insurance on buildings, equipment, fences and other property, as well as general liability insurance. These costs are built into the rental charges. Operators would need to insure livestock, feed, and their own equipment.

Time and Basis of Payment

The date that rental payments are due typically coincides with the periods in which the tenant receives cash income. Annual or semi-annual payments are common, although for a continuous livestock production facility monthly payments may be more reasonable. An exception might be a grain bin, which generally can be used only once a year, even if the grain is stored for just a few months.

Some rental rates for buildings and equipment are based on the actual level of usage rather than a fixed annual amount. For example, a swine finishing facility may be rented for a set rate per head finished, or a machine shed may be rented for so much per square foot of space used. In these cases the owner and operator need to agree on how the level of usage will be determined.

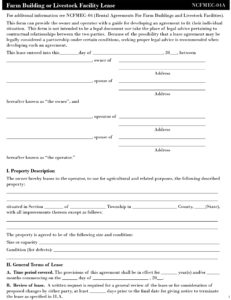

Common Provisions in a Lease

One of the primary functions of a written lease agreement is to anticipate possible developments and problems and state how to handle such problems if they actually develop.

Putting the terms of the rental agreement in writing has the following advantages:

- It is evidence that a legally binding agreement exists.

- It encourages a detailed discussion and statement of the agreement, which assures a better understanding by both parties.

- It serves as a record of the terms originally agreed upon and accepted.

- It provides a valuable guide for the heirs if either the owner or operator dies.

- It serves as evidence of the business arrangement for income or estate tax purposes.

The following points need to be covered in a written lease in order for it to provide the advantages listed above:

- Names, addresses and telephone numbers and other contact information of persons entering into the lease agreement, and corresponding signatures.

- Description of the property, including type, size, location and condition.

- Beginning and ending dates of the agreement.

- Termination procedure, including advance notice requirements.

- Rental charges, including amount per time period or per unit of use or production, time and place of payment, and penalties for non-payment or late payment.

- Specific use to be made of the structure or equipment. Limitations on use can be stated, such as the maximum number of livestock to be housed or the maximum number of cows to be milked.

- Responsibilities of both owner and operator, such as provision of insurance coverage, payment of operating repairs and capital repairs, removal of livestock wastes, provision for water, electricity and other utilities, inspections, rights of entry, assignment of rights and coverage of damages.

- Arbitration procedure to settle differences between owner and operator.

The example lease contained in this bulletin covers these points. Unwanted provisions can be crossed out or omitted and other provisions added. For long-term agreements the lease should be reviewed every few years to be sure rates and terms are still acceptable.

Worksheets

*Originally published on Ag Lease 101 by North Central Farm Management Extension Committee. http://www.aglease101.org

TAGS:

TEAM LINKS:

RELATED RESOURCES

UPCOMING EVENTS

We are taking a short break, but please plan to join us at one of our future programs that is a little farther in the future.