March 6, 2020

Deterioration of Working Capital

by Michael Langemeier

Introduction

Working capital represents the liquid funds that a business has available to meet short-term financial obligations. The amount of working capital a business has is calculated by subtracting current liabilities from current assets. Current assets include cash, accounts receivable, inventories of grain and market livestock, prepaid expenses (e.g., feed, fertilizer, and seed inventories), and investment in growing crops. Current liabilities include accounts payable, unpaid taxes, accrued expenses, including accrued interest, operating lines of credit, and principal payments due in the upcoming year on longer term loans.

Working capital provides the short-term financial reserves that a business needs to quickly respond to financial stress as well as to take advantage of opportunities. It provides a buffer to financial downturns that might impair the farm’s ability to purchase inputs, service debt obligations, or to follow through on its marketing plan. It also provides the financial resources to quickly take advantage of opportunities that might develop (e.g., rent additional ground; purchase land; add a family member to the operation).

This article discusses recent trends in working capital and differences in working capital among farms, and provides working capital benchmarks. Data from USDA-ERS, the Kansas Farm Management Association, and the Center for Farm Financial Management in Minnesota is utilized.

Working Capital Benchmarks

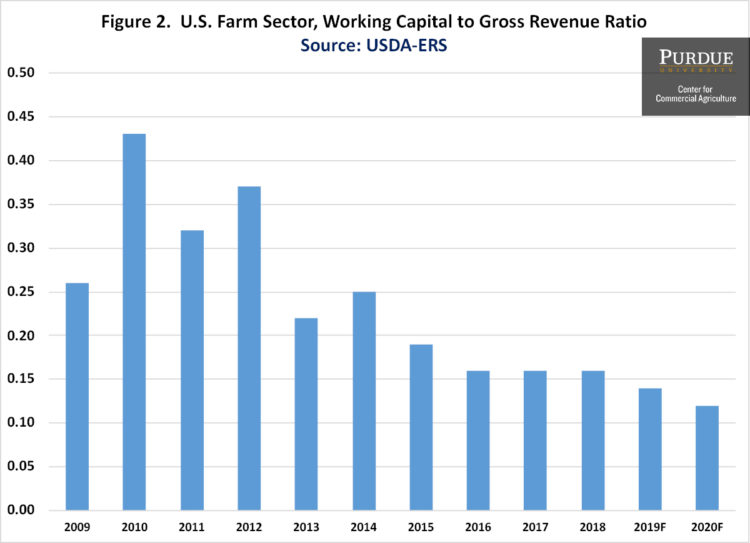

How much working capital does a farm need? The answer to this question depends on both the risk and size characteristics of the farm, and volatility of the business climate. In a volatile business climate and when a farm engages in enterprises that exhibit relatively more variability of net returns, more working capital is needed. Larger farms also need more working capital, so it is best to determine the amount of working capital buffer relative to either gross revenue, value of farm production, or total expense. Working capital to gross revenue, working capital to value of farm production, or working capital to total expense ratios above 0.35 are commonly used thresholds by financial analysts and would be considered an adequate level of working capital to weather a one- or two-year downturn. When the working capital ratios fall below 0.20, a farm may have trouble repaying loans.

Trends in Working Capital

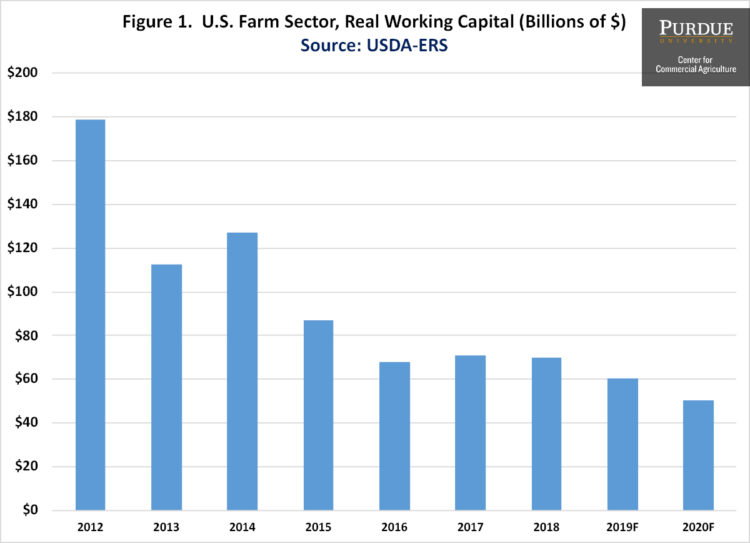

Figure 1 illustrates the trend in working capital for the U.S. farm sector since 2012. Working capital dropped from $165 billion in 2012 to an estimated value of $52 billion in 2020. The largest drops occurred from 2012 to 2015. Working capital has been below $75 billion, or less than one-half of what it was in 2012, since 2016.

The working capital to gross revenue ratio for the U.S. farm sector is depicted in figure 2. From 2009 to 2014, the working to gross revenue ratio ranged from 0.22 in 2013 to 0.43 in 2010. The ratio was above the 0.35 threshold in 2010 and 2012. Since 2015, the working capital to gross revenue ratio has been below 0.20. The 2020 projected ratio is an anemic 0.12.

Using FINBIN data summarized by the Center for Farm Financial Management at the University of Minnesota, the average working capital to gross revenue ratio declined from 0.431 in 2012 to 0.257 in 2018. Using a sample of Kansas Farm Management (KFMA) farms with continuous data from 1999 to 2018, Langemeier and Featherstone indicated that the working capital to value of farm production ratio peaked in 2015 at 0.838 and dropped to 0.607 in 2018, which was still above the pre-2007 levels.

Difference in Working Capital among Farms

The working capital to gross revenue ratio as well as other liquidity measures vary substantially among farms. Using FINBIN data summarized by the Center for Farm Financial Management at the University of Minnesota, the average working capital to gross revenue ratio in 2018 was 0.19. Approximately one-half of the farms had a ratio below 0.20. In contrast, approximately one-third of the farms had a ratio above 0.35. Of the farms that had a ratio below 0.20, approximately 60 percent of this group had a negative ratio, indicating that their current liabilities exceeded their current assets. Using KFMA farms with continuous data from 1999 to 2018, Langemeier and Featherstone indicated that, in 2018, 36 percent of the farms had a ratio below 0.35 and 27 percent of the farms had a ratio below 0.20.

Conclusions

This article provided working capital benchmarks and discussed trends in working capital and differences in working capital among farms. A substantial portion of farms have a ratio below 0.20. When the working capital to gross revenue is below 0.20, farms may have difficulty repaying loans. Just as importantly, when liquidity becomes very tight (e.g., working capital to gross revenue below 0.20), farms have very little flexibility with regard to their input purchases, or the timing of their commodity sales. In this situation, it also becomes increasingly difficult to borrow runs to replace machinery and equipment, or to rent or purchase land.

Citations

Langemeier, M. and A. Featherstone. “Examining Trends in Liquidity for a Sample of Kansas Farms.” Center for Commercial Agriculture, Purdue University, November 15, 2019.

TAGS:

TEAM LINKS:

RELATED RESOURCES

UPCOMING EVENTS

We are taking a short break, but please plan to join us at one of our future programs that is a little farther in the future.