How robots touch on the future of agriculture

Walking into Purdue’s Mechanisms And Robotic Systems (MARS) Lab feels like falling into a child’s imagination of what a lab could be. Giant robotic silver arms with black joints reach out from tables and up from the floor. Wires and 3D-printed bits and bobbles cover the graduate students’ bench space like jigsaw puzzle pieces waiting to be put together. A standing whiteboard is pushed against the far end of the room, scrawled over in doodles of cubes and equations that only an engineer could understand.

For Yu She, head of the MARS Lab in industrial engineering and a member of the Institute for Digital Forestry (iDiF), this is the future. “The goal for this lab is to develop robots that can be used in your daily life. Robots in industry are getting pretty good and can even do car assembly, but robots at home are still vacuum cleaners. Why aren’t they mowing your grass? Helping you with laundry or making your breakfast?”

These home-service robots have the potential to revolutionize not just your chores, but also the care industry. Mechanized care might offer independence for people with disabilities and the elderly, but several barriers remain to be overcome. While the technology is quickly becoming cheaper with 3D printers able to manufacture machine parts, some parts still haven’t been invented.

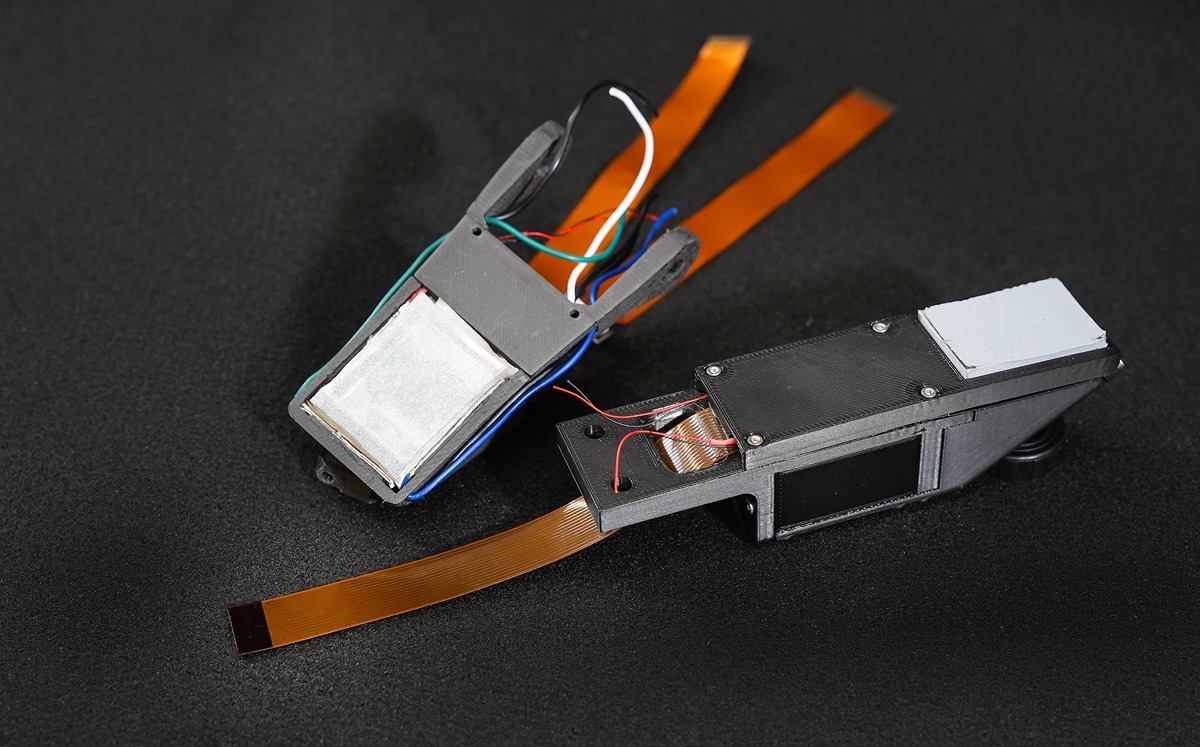

One thing robot researchers are trying to mechanize is the human sense of touch. Sheeraz Athar, one of She’s PhD students, is changing the game by re-thinking how touch works. He’s helped build a two-gripper robotic hand that has a “tactile sensor” and actually uses sight to feel objects.

“What we specialize in our lab are vision-based techniques in sensing,” Athar said. “So there's a camera inside the hand sensor that views objects through a silicon gel, which is like our outermost flexible layer of skin. When it contacts an object, that layer deforms. From that deformation, we can extract information like geometry and shear force.”

The MARS Lab is also working on teaching robots to combine different forms of sensory information to get a fuller picture and complete complicated tasks. A robot might have to look at a target object to pinpoint its location, use the specialized gel sensors to touch and manipulate it, and listen for sounds like the click of two objects fitting together to tell when a task is completed.

The lab recently found a real-world application where they never expected: agriculture.

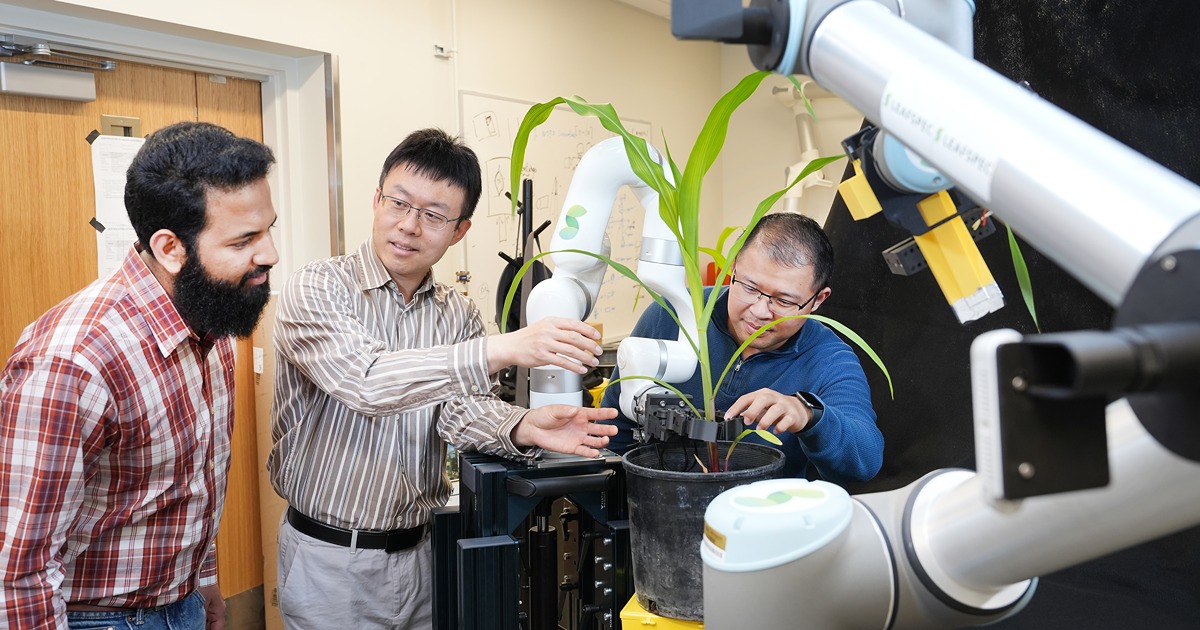

“I heard Jian Jin’s presentation on agriculture phenotyping, and I could immediately see what we could do: take the tactile sensor and have a direct application for agriculture and his work,” said She. “We started this conversation, sharing what we do and then planning to work together. We have been collaborating on various topics since then.”

Jian Jin, an associate professor in Purdue’s Agricultural & Biological Engineering Department and a member of the iDiF, says robotics has long been on his radar. Jin previously worked in creating phenotyping technology and facilities for DuPont Pioneer—now Corteva. He now works with Purdue’s world-leading Ag Alumni Seed Phenotyping Facility to image, analyze and record plant growth, health and yield.

Jin has also been thinking about how to make phenotyping technology more accessible. “We have 600 million farmers outside that cannot benefit from these facilities. We have really accelerated plant science research, but we wanted to extend this impact by outputting advanced phenotyping technologies to people outside universities and industry.”

Jin and his lab shrunk down the phenotyping facility into a hand-held imaging device they call LeafSpec, a 2021 Davidson Prize Winner for innovative design and multi-disciplinary collaboration. By holding a leaf against the LeafSpec’s camera, growers can get real-time and accurate information on stress diagnoses of their crop right on their smartphones, which could save money in targeted fertilizer and pesticide application, as well as disease prevention and management.

Scanning individual leaves of many plants across many fields throughout the growing season is a large labor and time cost to farmers. After connecting with She, Jin realized the potential of the MARS Lab robotics to mechanize LeafSpec.

This collaboration has so far resulted in a two-arm robotic system that holds corn plants steady by their stem and scans down the whole length of their leaves. Athar’s tactile sensor was instrumental for this.

Think of how you feel a leaf, how you might run your finger along its surface and trace the veins popping out. Leaves have several dimensions for a hand to think about, and there are inconsistencies from one leaf to another. The tactile and visual sensors on the robot have to actively respond to changes in leaf shape, texture and the angle to keep it next to the camera without breaking it.

Although these robotic arms are stationary, they are the first step to take automated LeafSpec out into fields. Jin, She and Athar are making plans for attaching robotic arms to drones or fans that pull leaves up to the camera as the drone hovers over plants and gathers data from them.

Jin and She’s labs are currently working together to apply these technologies to collect data on forest health. LeafSpec could be brought up into the canopy of trees to scan leaves humans can’t reach. The MARS Lab is joining other iDiF faculty, including computer scientists, to think about how robots could help gather data underneath the canopy as well.

“I see this as a perfect story of multidisciplinary collaboration,” Jin said. “Dr. She is from an agricultural family, so he knows agriculture and is passionate about helping hard-working farmers laboring in the field. I know something about technology, and I'm from industry, so I know what the real-world needs are. I can quickly see how Dr. She’s coolest technologies can be applied to address issues in agriculture. We understand each other but have our own unique expertise that we bring to the table.”