How Do Local Knowledge Systems Respond to Climate Change?

Integrating Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) systems, or the understandings, skills and philosophies developed by people groups over time, with scientific information is critical for achieving biodiversity conservation, climate change adaption and other environmental goals. But what is the best way to combine those systems to assist communities?

Integrating Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) systems, or the understandings, skills and philosophies developed by people groups over time, with scientific information is critical for achieving biodiversity conservation, climate change adaption and other environmental goals. But what is the best way to combine those systems to assist communities?

Dr. Zhao Ma and postdoctoral researchers Ruxandra Popovici and Anna Erwin and a multidisciplinary team studied the effect of climate change on crop farmers in Peru’s Colca Valley to assess the obstacles to adaptation strategies and the best way to address them in the future. The group’s findings are available in the article "How do Indigenous and local knowledge systems respond to climate change?", which was recently published in Ecology and Society.

“We found that climate change is affecting farmers’ ability to predict stressors on their crops, and traditional local institutions are not adapting fast enough to deal with changes in climate,” Popovici explained. “Simply knowing about climate change is not enough to adapt. In many cases, farmers need additional assistance and resources in order to make a change. What was surprising is that we found tension with the climate change adaptation literature that emphasizes the importance of local knowledge in addressing climate change. In contrast, our interviewees reported a need for experts that would provide them with climate models showing the agricultural changes they can expect in the future (and less of a need being involved in the coproduction of knowledge).”

This information may be helpful in planning for future conservation and climate change interactions, suggesting that while coproduction and other attempts to include local knowledge might be beneficial for long-term climate change adaptation strategies, short-term strategies might require quick solutions and resources from experts that can help farmers address more urgent needs.

Methods and Findings

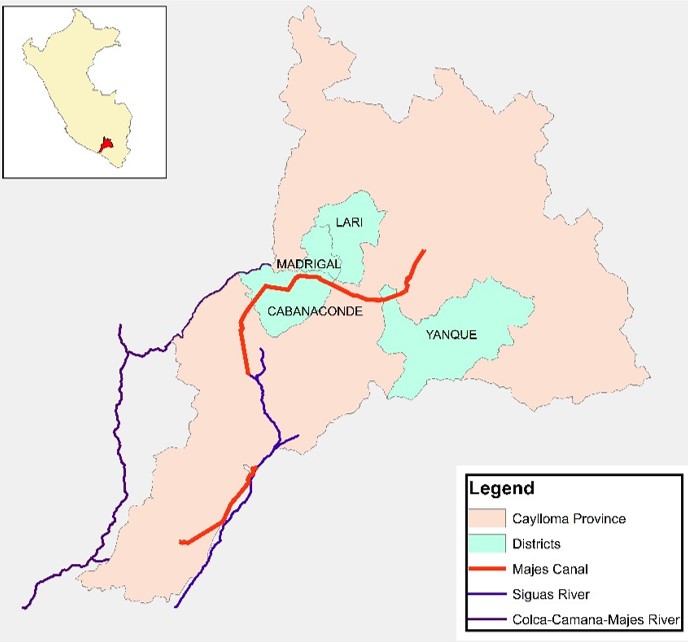

For this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with more than 100 farmers across four agricultural districts in the Colca Canyon area of the Caylloma province of Peru: Cabanaconde, Yanque, Lari and Madrigal. Interviewees were asked whether they had noted changes in climate over the last 10 years and whether these changed had affected their agricultural practices.

For this study, semi-structured interviews were conducted with more than 100 farmers across four agricultural districts in the Colca Canyon area of the Caylloma province of Peru: Cabanaconde, Yanque, Lari and Madrigal. Interviewees were asked whether they had noted changes in climate over the last 10 years and whether these changed had affected their agricultural practices.

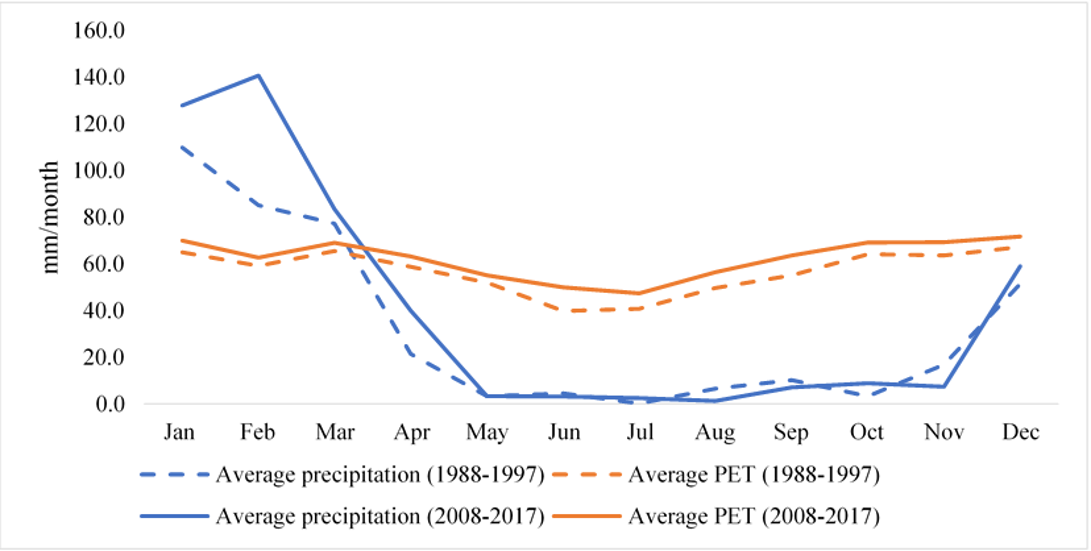

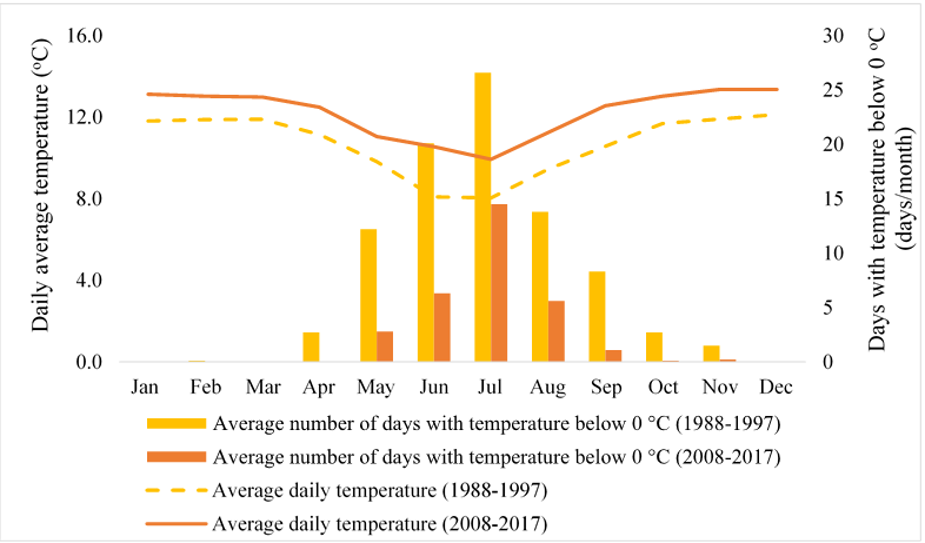

Researchers also analyzed climate trends from a 30-year period (1988-2017) compiled by Moraes et al. (2020), looking at precipitation, air temperature, potential evapotranspiration, the start of the rainy season and also days below zero degrees Celsius.

Farmers noted the occurrence of shifts in the rainy season, an increase in average temperature and an increase in unanticipated cold days, all of which were explained by climate trend data. However, crop planting and irrigation practices were not adapted despite the addition of this new information to the local knowledge base.

“Farmers’ awareness of changes in climate was not, on its own, sufficient to devise effective strategies for adapting to climate change. Although farmers were aware of shifting climate patterns, they were not always able to access the kinds of resources they needed in order to adapt accordingly,” the article states.

The study broke down specific limitations to the responsiveness to climate change and noted that lack of ability to respond rapidly prevented farmers from acting on their observations and need for adaptations. Researchers concluded that both short and long-term approaches are needed for climate-change adaptation, and to do so it is important to integrate Indigenous and local knowledge systems with immediate targeted expert consultations.

Writer: Wendy Mayer, Communications Coordinator